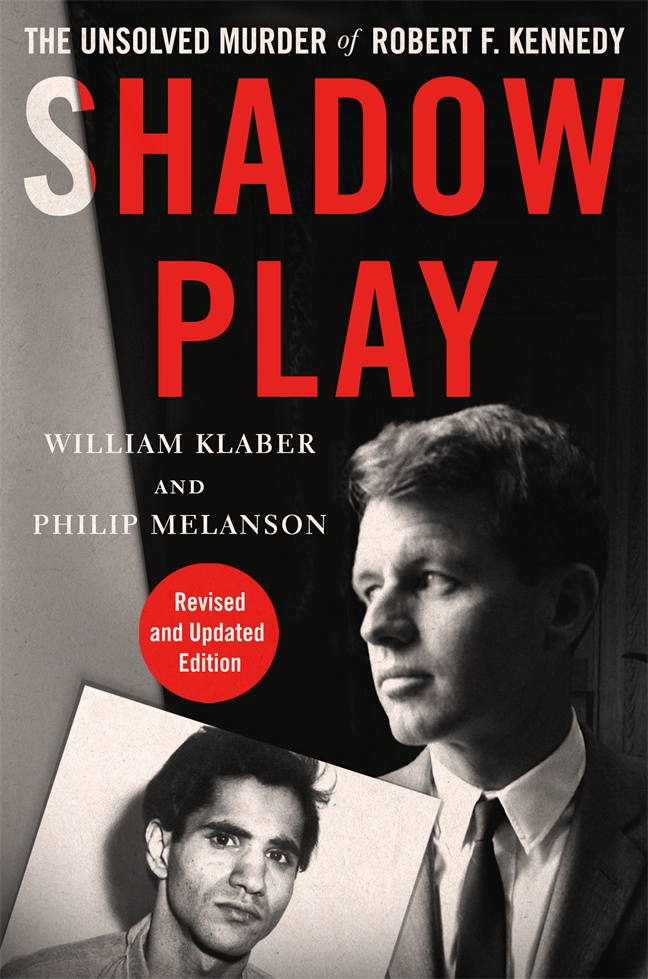

by William Klaber & Philip Melanson

Updated for the 50th anniversary of Robert F. Kennedy’s murder, Shadow Play explores ignored witness accounts, coerced testimony, bullet-hole evidence, and other issues surrounding the political homicide.

Robert F. Kennedy

On June 4, 1968, just after he had declared victory in the California presidential primary, Robert F. Kennedy was gunned down in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel. Captured a few feet away, gun in hand, was a young Palestinian-American named Sirhan Sirhan. The case against Sirhan was declared “open and shut” and the court proceedings against him were billed as “the trial of the century”; American justice at its fairest and most sure. But was it? By careful examination of the police files, hidden for twenty years, Shadow Play explores the chilling significance of altered evidence, ignored witnesses, and coerced testimony. It challenges the official assumptions and conclusions about this most troubling, and perhaps still unsolved, political murder. Keep reading for an excerpt of William Klaber and Philip Melanson’s Shadow Play.

* * * * *

John Howard stepped through the door of the interrogation room and stared at the man seated in the chair. The prisoner, now showered, looked considerably better than he had before. Still, nobody knew his name.

An hour earlier Howard had told the prisoner, who had not been saying anything, that he had the right to remain silent. The slightly built, dark young man responded politely that he wished to “abide” by that “admonishment.” Well, that settled one thing; he could speak English. The deputy district attorney then offered a card with his telephone number: “If you want to talk to someone.”

Upon learning that the husky man in a suit was with the Los Angeles County DA’s office, the prisoner brightened and made his first non-perfunctory utterance since being in custody.

“Remember Kirschke?”

“I’ve known Jack for a long time,” answered a surprised Howard. “Why? Why did you ask that?”

“Interested,” the young man replied.

When John Howard got word a little later that the prisoner was asking to speak with him, he had forgotten all about Jack Kirschke. But the mysterious young man had not. To Howard’s chagrin, that is what he wanted to talk about.

“Yeah, we were talking about Kirschke.” Howard sighed, thinking that if they could get going about one thing it might lead to something else. “How come you followed that?”

“No, I didn’t follow it. I was hoping you’d clue me in on it, brief me on it, you might say.”

“It was a tough lawsuit. You’d have to know Jack. He was a deputy. I worked with him.”

“No, I mean—I mean the substance of the case.”

Jack Kirschke, like Howard, had been a deputy district attorney in Los Angeles. Several years earlier, he had been charged with the bedroom murder of his wife and her lover. The story made headlines for months.

“The substance,” Howard found himself saying, “actually was whether or not he was the guy that—there is no question his wife and a friend of hers got shot. There is no question about that. The question was who did it.”

But the prisoner wanted to talk about things more subtle than guilt or innocence. Had Jack Kirschke sown the seeds of his own destruction? In prosecuting others, did he feel he was above the law?

Suddenly the absurdity of the situation overwhelmed John Howard. Only hours before, the unidentified man in front of him had gunned down a United States senator, a presidential candidate. Now the two of them were having a friendly philosophical discussion. Either this guy was one cool customer, or something was wrong. Howard’s instincts took over.

“Do you know where we are now?” he asked. “I’ve told you you’ve been booked.”

“I don’t know,” replied the prisoner.

“You are in custody. You’ve been booked. You understand what I’ve been—”

“I have been before a magistrate, have I or have I not?”

“No, you have not. You will be taken before a magistrate as soon as possible. You’re downtown Los Angeles in the central jail. Now when I say this, if you know, you know—you know—I’m not saying this because I don’t know. We’re not communicating very well up to now, but you are downtown Los Angeles, okay? This is the main jail for the L.A. Police Department. You’ll be booked into a cell . . . do you understand that? Do you understand where you are?”

***

At about 4 A.M. Howard was relieved by George Murphy of the DA’s office and Sergeant Bill Jordan of the Los Angeles police. The prisoner still had not revealed his identity, nor had there been any talk about what had happened earlier that night. The conversations that did occur were the kind one might have in a bus-terminal waiting room. The officers asked the prisoner if he had an extensive education.

“No,” he replied. “I read a lot.”

“I gathered that,” said Jordan. “You like to read?”

“I enjoy it.”

“What do you like to read?” asked Murphy.

The prisoner tried to engage the officers in a discussion of To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee’s Depression-era novel about a white attorney in rural Alabama who defends a black man unjustly accused of rape. The novel won a Pulitzer Prize in 1960 and touched the conscience of the nation. Now, in the basement of police headquarters, it was being offered as a topic of conversation by the captured assailant of a United States senator. Neither Murphy nor Jordan, however, had read the book.

The men found common ground for conversation when the prisoner confessed that he didn’t understand the stock market and asked the officers what they knew about it.

“A lot of money changes hands on stocks,” said Jordan. “It’s kind of a legalized gambling is about what it boils down to.”

“If you wanted to buy stock, you’d do it just the same way I would,” said Murphy.

“How?” asked the prisoner.

“Call up a broker and say, ‘I’d like to buy some stock.’ ”

“But, hell,” the prisoner replied, “if you want to gamble, you can call up any old bookie and say, ‘Play such and such a bet.’ ”

“No,” said Jordan, “it’s accepted, no stigma attached; even in church they accept the stock market.”

“I never had any money to fool around with stocks,” Murphy added. “Policemen don’t make that much money.”

“I wish I had,” replied the prisoner. “I wish I had some. Really, that would be a good adventure to—to experiment with.”

From money the conversation got philosophical once again.

“What is justice?” asked the prisoner.

“Fair play,” replied Murphy.

“What is fair play?” asked the prisoner.

“Well,” said Murphy, “fair play is only that you don’t take advantage of anybody.”

“Right,” agreed the prisoner. “Treat others as you would want them to treat you, that’s what Jesus said. Beautiful thing.”

“Do you go along with that?” Murphy asked the man who had just shot six people he had never met.

“Very much so, sir. Very much.”

***

The prisoner, nursing a sprained knee and sitting in a wheelchair, was rolled into the prison chapel, now devoid of religious insignia, as it had been converted into a makeshift courtroom for security reasons. Clad in blue dungarees and a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up, the accused was lifted in his chair by four deputy sheriffs to a raised platform, where he faced superior court judge Arthur Alarcon at the altar. Robert Kennedy had been dead a day.

Earlier, the Los Angeles County Grand Jury had convened in the chapel to hear twenty-three witnesses before handing down an indictment for murder. Now the prisoner was to be arraigned. The proceeding took about half an hour. The prisoner’s court-appointed lawyers, Richard Buckley and Wilbur Littlefield, did most of the talking. Could they postpone the plea until psychiatric tests could be completed? The judge agreed.

During the proceedings, Judge Alarcon pronounced the defendant’s name “SEER-han Bishara SEER-han.” The defendant, who two days before would not reveal his identity to anyone, now made his first public statement: “It’s not SEER-han,” he said in a voice heard throughout the room. “It’s pronounced Sir-han.”

William Klaber earned a Golden Reel Award nomination in 1993 for The RFK Tapes, a nationally broadcast, one-hour public radio documentary on the murder of Robert Kennedy.

Philip Melanson was a political science professor and the chair of the Robert Kennedy Assassination Archives at University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. He died in 2006.

The post The Unsolved Murder of Robert F. Kennedy appeared first on The History Reader.

Powered by WPeMatico