by Philip Jett

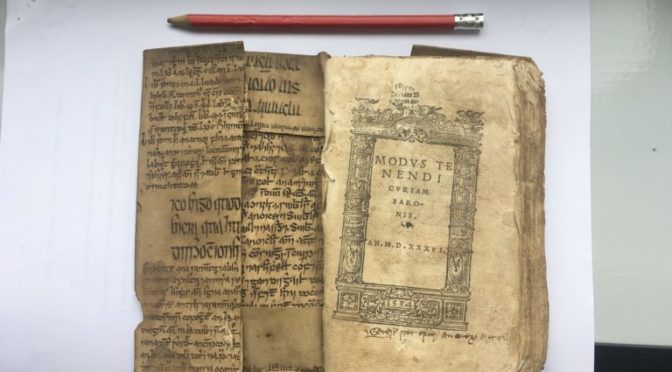

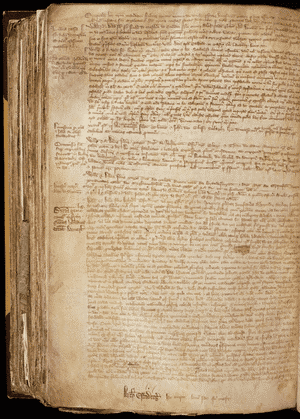

“My name is Patrick… I was taken prisoner. I was about sixteen… I was taken into captivity in Ireland, along with thousands of others,” Saint Patrick revealed in two letters written in the fifth century called Saint Patrick’s Confessio.

Did you know that Saint Patrick was born outside Ireland with a name other than Patrick, and he professed to be an atheist in his youth? What’s more, he likely would not have become a saint nor have a day for us to celebrate if he had not been kidnapped.

My maternal grandmother was a McQueen (Irish) and my paternal grandfather was a Jett (English), thus explaining my lifelong internal conflict. Notwithstanding my Irish blood, I must confess that my only thoughts of Saint Patrick have come while drinking green beer during March Madness. I do not believe I am alone in this ritual. After all, I live in Nashville, Tennessee, and although it is often called the “Protestant Vatican” and the “Buckle of the Bible Belt,” it isn’t due to the citizenry’s collective knowledge of the Catholic saints, I can assure you.

My maternal grandmother was a McQueen (Irish) and my paternal grandfather was a Jett (English), thus explaining my lifelong internal conflict. Notwithstanding my Irish blood, I must confess that my only thoughts of Saint Patrick have come while drinking green beer during March Madness. I do not believe I am alone in this ritual. After all, I live in Nashville, Tennessee, and although it is often called the “Protestant Vatican” and the “Buckle of the Bible Belt,” it isn’t due to the citizenry’s collective knowledge of the Catholic saints, I can assure you.

I can state with confidence, however, that St. Patrick’s Day is the only cultural and religious holiday where folks drink barrels of green beer, display shamrocks and dancing leprechauns, and adorn themselves in bright green attire and plastic jewelry. Actually, light blue was once the holiday’s color until green replaced it during the eighteenth century. Tradition has it that green makes a person invisible to mischievous pinching leprechauns, and the shamrock derives from the belief that Saint Patrick taught the Holy Trinity using a three-leafed clover.

St. Patrick’s Day is one of the most celebrated days in the world, even observed in countries with little if any Irish heritage, though nowhere more than in the United States whose Irish-descended population is seven times greater than that of Ireland. The first St. Patrick’s Day celebration in the Americas took place in Boston in 1737, and the first recorded St. Patrick’s Day parade in the world took place in 1762 in New York City (Ireland didn’t have a parade until 1903). General George Washington granted his troops the day off for St. Patrick’s Day in 1780. And the tradition and celebrations still continue, where cities like Boston, New York, Savannah, and Chicago with its green river have ostentatious parades embraced by hundreds of thousands of participants. Simply staggering . . . the scope of the parades, that is.

St. Patrick’s Day is one of the most celebrated days in the world, even observed in countries with little if any Irish heritage, though nowhere more than in the United States whose Irish-descended population is seven times greater than that of Ireland. The first St. Patrick’s Day celebration in the Americas took place in Boston in 1737, and the first recorded St. Patrick’s Day parade in the world took place in 1762 in New York City (Ireland didn’t have a parade until 1903). General George Washington granted his troops the day off for St. Patrick’s Day in 1780. And the tradition and celebrations still continue, where cities like Boston, New York, Savannah, and Chicago with its green river have ostentatious parades embraced by hundreds of thousands of participants. Simply staggering . . . the scope of the parades, that is.

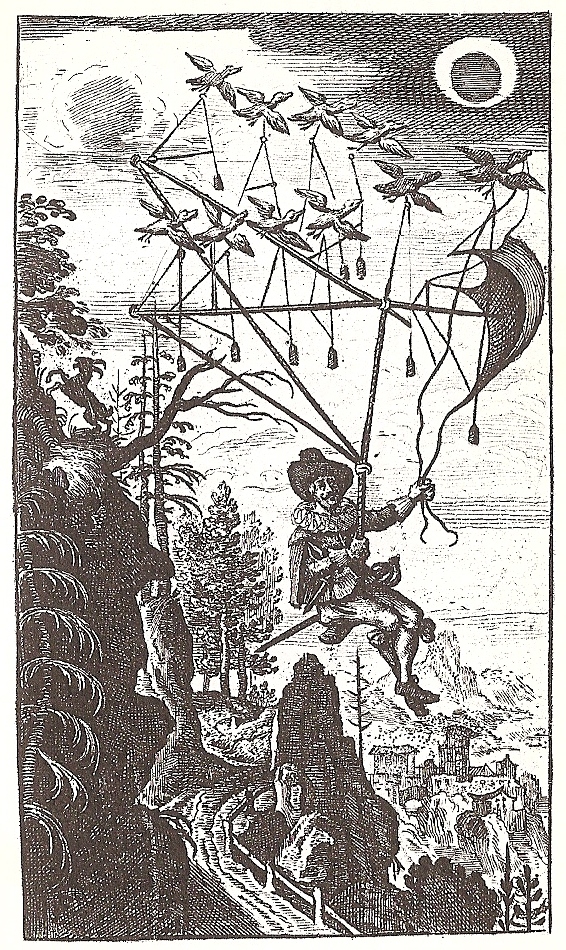

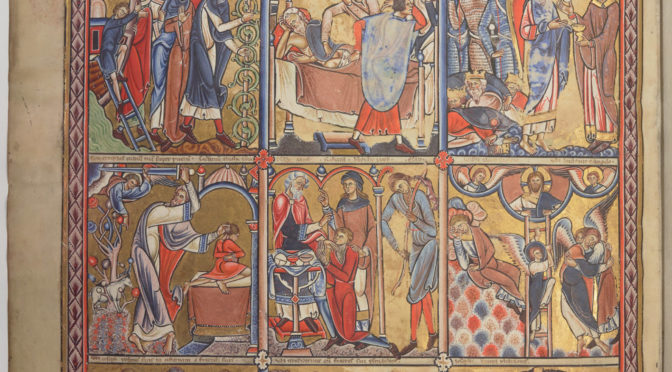

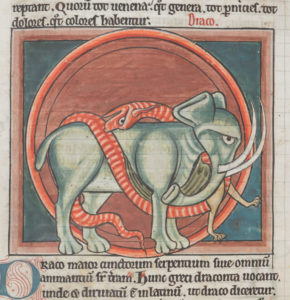

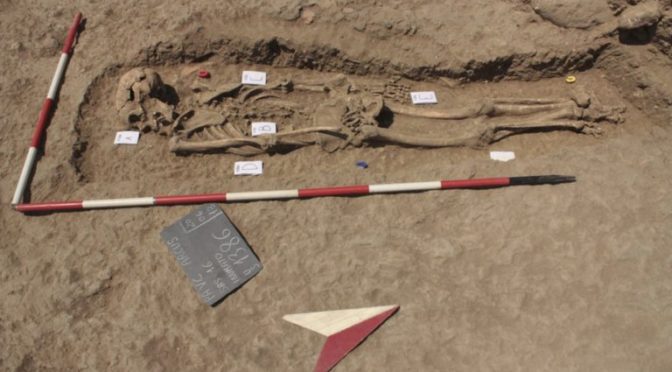

So, who is Saint Patrick? He was born Maewyn Succat around 385 A.D. in what is believed to be modern-day Wales or Scotland to Roman parents (Calpurnius and Conchessa) of some nobility. Maewyn, a self-described atheist, frolicked about unstrained by Christianity during his youth. Just before his sixteenth birthday, Irish pirates, who frequently trolled and raided villages along the western coast of Roman Britannia (Wales and England), took Maewyn captive. They sold him to Meliuc, a sheep owner in what is now County Antrim, Northern Ireland. For six years, Maewyn tended his master’s sheep on Slemish Mountain as a slave. During this time of suffering, Maewyn recalled later that he prayed to God one hundred times each day and then again each night until, around the age of twenty-two, he believed he heard a voice interrupting the night’s bleating: “It is well that you fast; soon you will go to your own country… See, your ship is ready.”

Since peyote is not indigenous to the pastures of Slemish Mountain, Maewyn believed the voice could only be divine and so he humbly obeyed. Energized by his new-born Christian faith, he trekked two hundred miles across Ireland to Wexford where he boarded a ship bound for Britannia. There, he was reunited with his parents. After much feasting, Maewyn’s spirit moved him to travel to Roman Gallia (in France) where he studied and became a priest. He was thereafter known as Patricius (Latin for Patrick). Patrick said he soon experienced a vision of a man named Victoricus beckoning him back to Ireland to preach the gospel: “We beg you, holy boy, to come and walk again among us.” Once again, Patrick’s parents lost him to Ireland, except this time as a missionary and later a bishop.

Since peyote is not indigenous to the pastures of Slemish Mountain, Maewyn believed the voice could only be divine and so he humbly obeyed. Energized by his new-born Christian faith, he trekked two hundred miles across Ireland to Wexford where he boarded a ship bound for Britannia. There, he was reunited with his parents. After much feasting, Maewyn’s spirit moved him to travel to Roman Gallia (in France) where he studied and became a priest. He was thereafter known as Patricius (Latin for Patrick). Patrick said he soon experienced a vision of a man named Victoricus beckoning him back to Ireland to preach the gospel: “We beg you, holy boy, to come and walk again among us.” Once again, Patrick’s parents lost him to Ireland, except this time as a missionary and later a bishop.

While some Christians already lived in Gaelic Ireland, Patrick is credited with converting thousands and making Christianity the predominant religion in Ireland. Many years after Patrick’s death, purportedly on March 17, 461 A.D, Patrick was bestowed the moniker, “Saint Patrick,” even though he wasn’t officially canonized by a pope at that time, a process that didn’t come until the twelfth century. He is believed to be buried at Hill of Down, in what is now Down Cathedral, in Downpatrick, Northern Ireland.

Young Maewyn endured much suffering during his captivity, as it is with most kidnappings. Yet, his suffering and resulting faith provided him the strength as Patrick to inspire the Irish people and become their patron saint. For the rest of us, we received one heck of a crazy holiday.

PHILIP JETT is a former corporate attorney who has represented multinational corporations, CEOs, and celebrities from the music, television, and sports industries. He is the author of The Death of an Heir: Adolph Coors III and the Murder That Rocked an American Brewing Dynasty. Jett now lives in Nashville, Tennessee.

The post A Kidnapped Boy Becomes a Patron Saint appeared first on The History Reader.

St. Patrick’s Day is one of the most celebrated days in the world, even observed in countries with little if any Irish heritage, though nowhere more than in the United States whose Irish-descended population is seven times greater than that of Ireland. The first St. Patrick’s Day celebration in the Americas took place in

St. Patrick’s Day is one of the most celebrated days in the world, even observed in countries with little if any Irish heritage, though nowhere more than in the United States whose Irish-descended population is seven times greater than that of Ireland. The first St. Patrick’s Day celebration in the Americas took place in  Since peyote is not indigenous to the pastures of Slemish Mountain, Maewyn believed the voice could only be divine and so he humbly obeyed. Energized by his new-born Christian faith, he trekked two hundred miles across Ireland to Wexford where he boarded a ship bound for Britannia. There, he was reunited with his parents. After much feasting, Maewyn’s spirit moved him to travel to Roman Gallia (in France) where he studied and became a priest. He was thereafter known as Patricius (Latin for Patrick). Patrick said he soon experienced a vision of a man named Victoricus beckoning him back to Ireland to preach the gospel: “We beg you, holy boy, to come and walk again among us.” Once again, Patrick’s parents lost him to

Since peyote is not indigenous to the pastures of Slemish Mountain, Maewyn believed the voice could only be divine and so he humbly obeyed. Energized by his new-born Christian faith, he trekked two hundred miles across Ireland to Wexford where he boarded a ship bound for Britannia. There, he was reunited with his parents. After much feasting, Maewyn’s spirit moved him to travel to Roman Gallia (in France) where he studied and became a priest. He was thereafter known as Patricius (Latin for Patrick). Patrick said he soon experienced a vision of a man named Victoricus beckoning him back to Ireland to preach the gospel: “We beg you, holy boy, to come and walk again among us.” Once again, Patrick’s parents lost him to