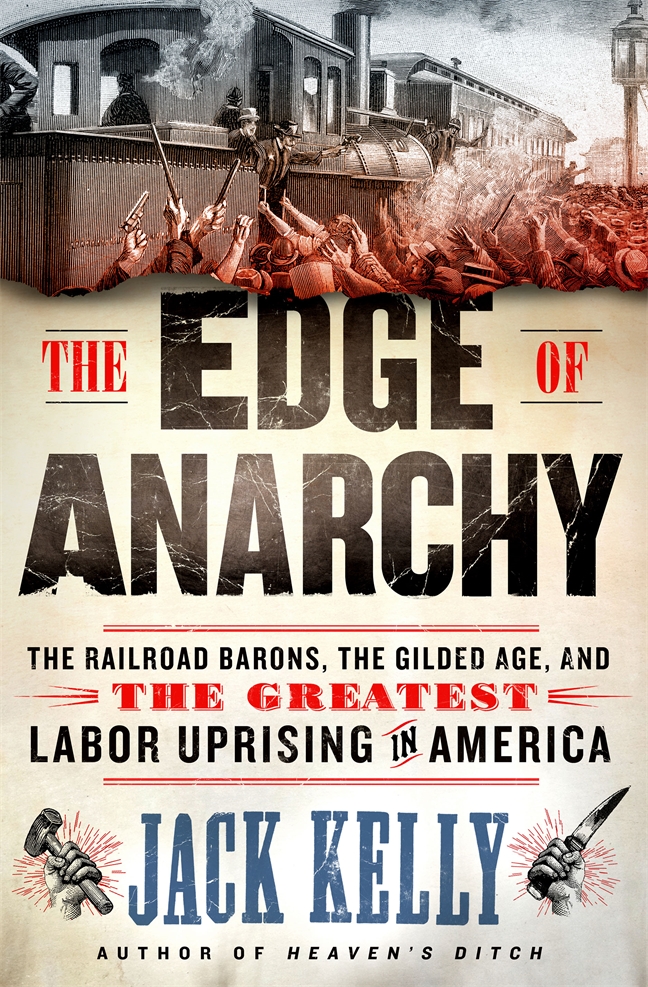

by Jack Kelly

The year 2019 marks the 150th anniversary of the completion of the first transcontinental rail line. The explosive growth of railroads had, by the 1890s, created the world’s greatest transportation system and made American railroad corporations the biggest businesses in the world.

In the summer of 1894, the employees of those railroads joined in a sympathy strike that virtually shut down the roads, especially in the West. They were supporting workers who made Pullman cars in Chicago, but, according to The New York Times, the real struggle was “between the greatest and most powerful railroad labor organization and the entire railroad capital.”

Chicago World’s Fair, Excerpt from The Edge of Anarchy

They came by the millions and tens of millions. Almost one in every five Americans made the trek to Chicago that summer for the world’s fair. Their reaction to the spectacle was summed up by a diarist who wrote: “My mind was dazzled to a standstill.”

Almost all who came, came by train. Those who could afford it rode a Pullman car, the epitome of luxurious travel. A Pullman sleeper offered room to spread out, elegant service, and the delicious pleasure of status. Fairgoers were headed to Chicago to shake hands with the future, and in the Pullman car the future seemed to be reaching out to greet them.

Almost all who came, came by train. Those who could afford it rode a Pullman car, the epitome of luxurious travel. A Pullman sleeper offered room to spread out, elegant service, and the delicious pleasure of status. Fairgoers were headed to Chicago to shake hands with the future, and in the Pullman car the future seemed to be reaching out to greet them.

Those who had not had the privilege of riding on one could take in all the latest models at a display mounted by the Pullman’s Palace Car Company in the fair’s Transportation Building. The carved rosewood, Axminster carpets, polished brass, fringed valances, and cascades of curtains and draperies beloved by Victorians all made Pullman travel an adventure in hedonism. By day, a Pullman was a fantastic parlor room on wheels. When night came, a smiling porter turned a pair of facing seats into a bed and produced a second berth from a compartment along the ceiling. He arranged heavy curtains, pristine damask sheets, and mahogany partitions, transforming the car into a comfortable dormitory.

The lucky few, railroad magnates or politicians, might be given a guided tour of the exhibit by the man himself, George Mortimer Pullman. The sixty-two-year-old progenitor of these marvels was one of Chicago’s richest entrepreneurs. Many fair visitors could remember the stagecoach days when no man traveled on land faster than the pace of a team of horses. Long train trips had demanded new technology—and Pullman had provided it. The sleeping car had become so closely associated with one company that it was coming to be called simply a pullman. The understated booklet distributed by the company gushed a bit when it called the inception of the Pullman firm, now valued at $60 million, “one of the century’s great civilizing strides.”

Pullman’s name and face were well known across the country—he had made sure of that. His wide, nearly unlined features were those of a tired baby. His hair had gone white and he wore on his chin a goat-like tuft of beard, which boys of the day called a dauber. His imperious eyes were always sizing up.

George Pullman represented a relatively new type in America, a “businessman.” He was a man of affairs, a man on the lookout for the new. A businessman’s key skill was organizing an enterprise and raising the money to fund it. Pullman knew how to gather resources, command men, and negotiate deals. Early in his career, he had begun to list his profession simply as “gentleman.”

The assertion by his publicity machine that George Pullman had invented the modern sleeping car was less than accurate. Most of the credit went to a man named Theodore T. Woodruff, an upstate New York wagon maker. But the mechanics of the car had evolved over decades, and Pullman had introduced his share of innovations.

What was beyond doubt was that Pullman had devised the most efficient system for making money from the sleeper. He saw each car not as a product but as a revenue stream. He retained ownership and allowed the various railroads to haul the cars under contract. The railroads profited because the luxury cars attracted customers. Pullman profited even more as each passenger paid him a hefty fee for the upgrade.

Pullman also understood that monopoly was the path to profit, and by 1893 he was well on his way to absorbing all other sleeping-car manufacturers into his company. A Pullman brochure boasted that the company employed fifteen thousand and ran its cars over enough track mileage to stretch five times around the circumference of the earth.

Pullman asserted that he was free of “the fever of rapid wealth-getting.” He could afford to be. He and his wife, Hattie, floated among the highest tiers of Chicago’s social heaven. An observer called him a lordly man. Reserved of speech, he let his possessions speak for him.

* * *

In 1831, the year George Pullman was born in a remote hamlet in the western end of New York State, a group of Americans at the other end of the state were taking a ride on America’s very first steam-powered passenger railroad. It was the beginning of the most stunning transformation in the nation’s history. During Pullman’s lifetime, private corporations laid more than 175,000 miles of rail, including five transcontinental lines.

In 1831, the year George Pullman was born in a remote hamlet in the western end of New York State, a group of Americans at the other end of the state were taking a ride on America’s very first steam-powered passenger railroad. It was the beginning of the most stunning transformation in the nation’s history. During Pullman’s lifetime, private corporations laid more than 175,000 miles of rail, including five transcontinental lines.

“Americans take to this contrivance, the railroad,” Ralph Waldo Emerson had observed, “as if it were the cradle in which they were born.” In the three decades since the Civil War, the railroads had proliferated into a great tangle of trunk lines and branch lines through the East and Middle West. When builders pounded the golden spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869, they tied together a continent. The New York Central main line ran from the Atlantic coast to Chicago. The mighty Pennsylvania system extended an arm across the Keystone State and spread its fingers into Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and beyond. The Southern Pacific, the Union Pacific, and the Santa Fe had erased the frontier. Enormous combines had gobbled individual rail lines, and the railroad corporations had become the most extensive business enterprises in history.

The needs of the railroads had led to an explosion in the production of iron and steel, of coal, copper, oil, and machine tools. The corporations’ thirst for capital had established Wall Street as a national money market. The access to far-flung markets that the railroads made possible fueled the rapid growth of other businesses on a scale previously inconceivable.

Chicago was the “Rome of the railroads.” Lines converged on the city from every direction. Fair visitors from New York, Philadelphia, and Washington boarded the Exposition Flyer to skim across the continent at eighty miles an hour, barely pausing in the headlong rush toward what trainmen called the “boss town of America.”

Chicago’s elite citizens had made a mighty effort to win the Exposition for their town. George Pullman had pledged $100,000 to finance the corporation that would mount the fair. Chicagoans were proud of the town’s lusty greatness. “Here of all her cities,” wrote author Frank Norris, “throbbed the true life—the true power and spirit of America.”

Chicago was in a continual hurry. Rudyard Kipling said that its inhabitants swore by the “Gospel of Rush.” The city had not existed when the century opened—now it was the sixth-largest metropolis on earth. Its densely packed commercial center pulsed with activity. “Compared to the bustle of Chicago,” a visitor said, “the bustle of New York seems like stagnation.”

The Columbian Exposition celebrated the acceleration of progress. Fairgoers could hardly wait to get home and describe the technology of tomorrow. They marveled at light bulbs, electric motors, generators, vacuum tubes, neon signs. They made some of the first long-distance

Telephone calls, listened to a phonograph, rode a moving sidewalk, and gazed in amazement at Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope, which displayed pictures that moved.

The fair was an enormous store window on the productivity of American commerce. The nation’s output of gold and silver, of telephones and electric lights, lumber and locomotives, sewing machines and pianos, could not be matched.

“The old nations of the earth creep on at a snail’s pace,” Andrew Carnegie declared, “the Republic thunders past with the rush of the express.”

* * *

But like the Gilded Age itself, Chicago had a dark side. Urban squalor was spreading there as it was in most American cities. Filth, disease, vice, and abject poverty had become the norm in districts crowded with pestilential tenements. The city, a reporter wrote, was both the “cynosure and cesspool of the world.” In 1891, two thousand citizens had died of typhoid.

Entering Chicago by train, travelers saw ugly stretches of smoky factories, slaughterhouses, freight yards, and slag heaps. An English visitor noted the “unrelieved ugliness” of the city. The working-class slums were swept by clouds of coal smoke and intersected by open sewers. The river that ran through the city’s heart was caked with “grease so thick on its surface that it seemed a liquid rainbow.” A Chicago newspaper complained that the city was permeated by a “solid stink. The river stinks. The air stinks. . . . No other word expresses it so well as stink.”

The filth and indigence coexisted alongside the crass opulence of the city’s parvenus. George Pullman’s home on fashionable Prairie Avenue sat at the center of what a journalist referred to a “the very Mecca of Mammon.” Kipling, although impressed by the city’s bustle, was put off by the many “terrible people who talked money through their noses.”

George Pullman thought he had found an answer to the city’s problems. His manufacturing operation was housed in one of the largest factories in the world, which he had built fourteen miles south of Chicago near Lake Calumet. He needed housing to induce skilled workmen to move to the remote location. Rather than leave the matter to the market, Pullman built a planned community that he called Pullman, Illinois.

The all-brick town, a company brochure stated, might be “the culminating product in its enduring benefits to mankind, of the principles on which the entire Pullman fabric is reared.” Those principles included the idea that “money could be safely invested in an elaboration of the utilitarian into the artistic and beautiful.”

Fairgoers were encouraged to make the fifteen-minute trip to see the unique urban village. They could stroll the grid of streets, take in the neat lines of houses, the town square, the elegant parks, the elaborate Arcade Building, theater, and library. It was a town where order and cleanliness were sovereign.

The model town was one of Chicago’s premier tourist attractions. Like the White City of the fair, it stood as a rebuke to Chicago’s squalid tenements. In Pullman, garbage was picked up, sewage pumped away, lawns neatly mowed.

The buildings of the White City were temporary, mere sheds dressed in overcoats of plaster and whitewash. Pullman was built of brick and mortar. Experts confirmed that the model town might well represent a hope-filled future for industrial workers. Yet just as the White City’s splendor was a false front, the enchanting surface of the model town hid problems that would, in less than a year, bring about a national crisis.

* * *

Although to Chicago’s boosters the Exposition was an occasion for unqualified optimism, others were skeptical. The explosion of marvels and conveniences that swelled the exhibit spaces marked the victory of rough-edged capitalism. Most industrial workers, making less than $10 for a sixty-hour week, could not afford to visit the fair. Almost three-quarters of the nation’s wealth was in the hands of two hundred thousand citizens.

The skeptical historian Henry Adams commented, “Chicago asked in 1893 for the first time the question whether the American people knew where they were driving.” Edward Bellamy, author of the popular utopian novel Looking Backward, declared that the motive of the exhibition “under a sham pretense of patriotism is business, advertising with a view to individual money-making.” Another observer called the fair a “triumph of materialism.”

The coming of the railroads and the instant communication of the telegraph had, in one generation, ruptured the isolation of rural communities. Before the Civil War, America had been a country of small towns with local business owners, local markets, local credit, and local news. Now every village was exposed not only to markets and opportunity but also to the inequality and dissatisfactions of the wider world.

The 1890 census had revealed that the frontier, the line of settlement that had been pushing west since the nation’s founding, no longer existed. During the fair, the scholar Frederick Jackson Turner would declare that it was the frontier that had shaped the American character. The availability of free land had allowed pioneers to turn their backs on rapacious landlords or demanding employers and head west. In the process, Turner asserted, they had developed a sense of self-reliance and practicality, along with the confidence, impatience, energy, and egalitarian morality that were distinctly American.

What would shape and inspire citizens now that the West was settled? What would happen to workers who could no longer escape urban slums? Were Americans destined to follow Europeans into a society in which an aristocratic upper class ruled over dependent laborers?

“The free lands are gone,” Turner wrote, “the continent is crossed, and all this push and energy is turning into channels of agitation.”

Abraham Lincoln had evoked a bygone era when he mused about a “penniless beginner” who at first works for wages, gradually saves a surplus, buys tools or land, and “then labors on his own account awhile, and at length hires another new beginner.” This early version of the American Dream was a hollow myth by the waning years of the century.

The labor scarcity of the first half of the century, which had enhanced workers’ power and freedom, had been erased by mechanization and mass immigration. The majority of workers were permanent hirelings, not budding entrepreneurs. In the workplace, independence— the defining feature of American society—had given way to the autocracy of bosses.

As industry grew without regulation, the bonds that connected workers to increasingly remote capitalists frayed. Railroad corporations were the first really big businesses in America and have been called “the seedbed of the American labor movement.” A series of strikes, beginning with a spontaneous railroad upheaval in 1877, had jolted the country with increasing frequency through the 1880s. During the past seven years, Chicago alone had seen more than five hundred work stoppages. The revolts rattled the moneyed elite. Ordinary citizens found themselves ranked among the “dangerous classes,” a common term for workers when they asserted collective rights.

Among those who would later attend and give a speech at the fair was a young union organizer named Eugene V. Debs. Lanky and energetic, the thirty-eight-year-old Debs had spent years promoting the interests of the firemen who stoked the boilers of the nation’s locomotives. He had come to see that traditional trade unions were inadequate in the face of consolidated railroad monopolies. Like George Pullman, Debs had a vision of a brighter future for industrial workers, but one that was far more radical than the paternalism of the model town. That summer, he planned to gather all railroad employees into a single, potent union. Once organized, they would demand their rights—he was determined that they would get them.

The post Railroads, the Chicago World’s Fair, and George Pullman appeared first on The History Reader.

In the sixteenth century, the Habsburgs and the Ottomans clashed for the dominance of Europe and the Mediterranean and engaged in a global rivalry that affected every polity along the shores of the Mediterranean.

In the sixteenth century, the Habsburgs and the Ottomans clashed for the dominance of Europe and the Mediterranean and engaged in a global rivalry that affected every polity along the shores of the Mediterranean. Over the course of about a century, from around 1120 to around 1220, the canons of St. Kilian, caretakers of the Neumünster church in Würzburg had frequent – one might even say constant – business dealings with the Jews of that same city.

Over the course of about a century, from around 1120 to around 1220, the canons of St. Kilian, caretakers of the Neumünster church in Würzburg had frequent – one might even say constant – business dealings with the Jews of that same city. Origins, Identities and ethnicities were all central concerns of Early Medieval writers

Origins, Identities and ethnicities were all central concerns of Early Medieval writers

Almost all who came, came by train. Those who could afford it rode a Pullman car, the epitome of luxurious travel. A Pullman sleeper offered room to spread out, elegant service, and the delicious pleasure of status. Fairgoers were headed to Chicago to shake hands with the future,

Almost all who came, came by train. Those who could afford it rode a Pullman car, the epitome of luxurious travel. A Pullman sleeper offered room to spread out, elegant service, and the delicious pleasure of status. Fairgoers were headed to Chicago to shake hands with the future,  In 1831, the year George Pullman was born in a remote hamlet in the western end of New York State, a group of Americans at the other end of the state were taking a ride on America’s very first steam-powered passenger railroad. It was the beginning of the most stunning transformation in the nation’s history. During Pullman’s lifetime, private corporations laid more than 175,000 miles of rail, including five transcontinental lines.

In 1831, the year George Pullman was born in a remote hamlet in the western end of New York State, a group of Americans at the other end of the state were taking a ride on America’s very first steam-powered passenger railroad. It was the beginning of the most stunning transformation in the nation’s history. During Pullman’s lifetime, private corporations laid more than 175,000 miles of rail, including five transcontinental lines.  The article was likely a tantalizing read for the day. Its author who later became President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, explored a

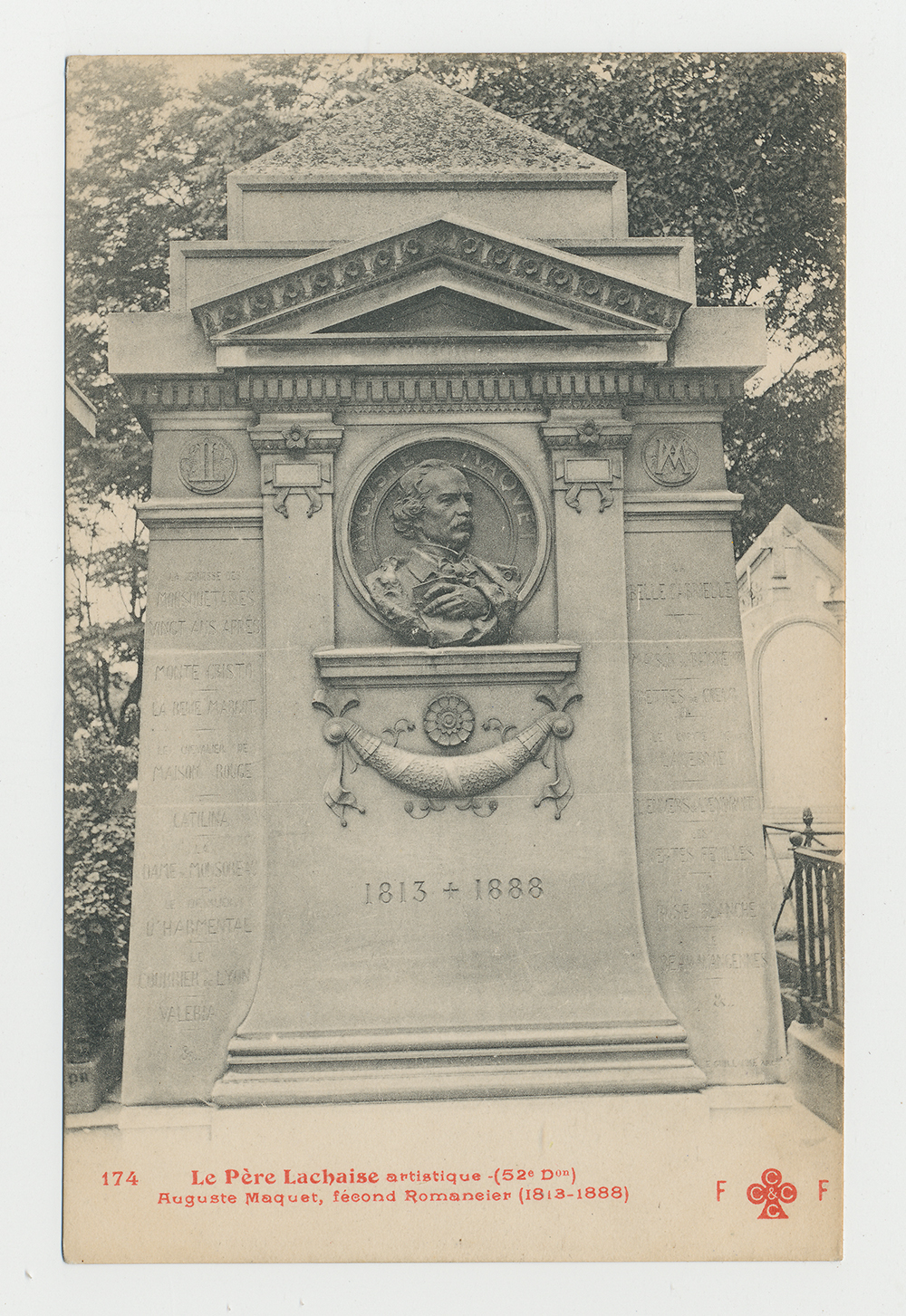

The article was likely a tantalizing read for the day. Its author who later became President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, explored a  The actual drawing by Howard Pyle commissioned for

The actual drawing by Howard Pyle commissioned for