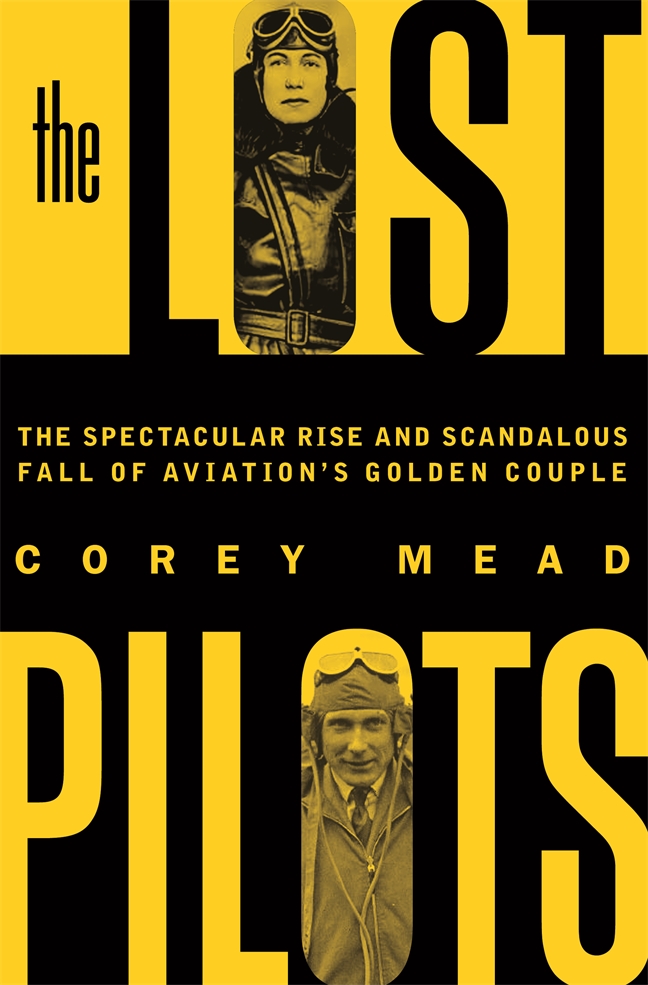

by Corey Mead

During the height of the roaring twenties, Jessie Miller longs for adventure. Fleeing a passionless marriage in the backwaters of Australia, twenty-three-year-old Jessie arrives in London and promptly falls in with the Bright Young Things, those gin-soaked boho-chic intellectuals draped in suits, flapper dresses, and pearls. At a party, Jessie meets Captain William Lancaster, married himself and fresh from the Royal Air Force, with a scheme in his head to become as famous as Charles Lindbergh, who has just crossed the Atlantic. Lancaster will do Lindy one better: fly from London to Melbourne, and in Jessie Miller, he’s found the perfect co-pilot.

Bill Lancaster and Chubbie Miller (Launceston, 1928)

Within months the two embark on a half-year journey across the globe, hopping from one colonial outpost to the next. But like world records, marriage vows can be broken, and upon their landing in Melbourne Jessie and William are not only international celebrities, but also deeply in love.

Yet the crash of 1929 catches up to even the fastest aviator, and the couple finds themselves in dire straits at their rented house on the outskirts of Miami—the bright glare of the limelight fading quickly. To make ends meet Jessie agrees to write a memoir, and picks the dashing Haden Clarke to be her ghostwriter. It’s not long before this toxic mix of bootleg booze and a handsome interloper leads to a shocking crime, a trial that rivets and scandalizes the world, and a reckless act of abandon to win back former glory.

The Lost Pilots is based on years of research, and full of adventure, forbidden passion, crime, scandal and tragedy. It is a masterwork of narrative nonfiction that firmly restores one of aviation’s leading female pioneers to her rightful place in history. Keep reading for an excerpt of this extraordinary true story.

* * * * *

On a muggy June night in 1927, a whirl of music, laughter, and conversation spilled from the open windows of an artist’s Baker Street studio in London. Paintings crowded the studio’s walls, but actual furniture was sparse, with only a low sofa, a few scattered cushions, and a single chair in which to sit. The party guests that night didn’t care; as they weaved throughout the crowded, cigarette-smoke-filled room, they felt an immutable kinship with the chaos and promise of the blossoming Jazz Age. They were young women in pearls and fashionable dresses, and young men in suits, their jackets abandoned in the heat, with sweating tumblers of gin and tonic eagerly clutched in their hands. They were the Bright Young Things of London, a pleasure-seeking assortment of wealthy socialites, bohemian artists, and middle-class rule-breakers, who gloried in their own irresponsibility and blissfully debauched fun. But beneath the bright, shiny facade, though they were not eager to admit it, the traumatic shadow of World War I lingered always over their frivolity, adding to it an air of desperation, a last-ditch alcohol-soaked escape from the black dog that trailed in their paths, no matter how privileged their social status and connections.

One of the party guests, a dark-haired, full-lipped twenty-five-year-old Australian woman with sparkling eyes who shared a one-room apartment downstairs, stood entranced at the scene before her, thrilled by the vitality of her newly adopted city. Jessie Keith-Miller—jokingly called “Chubbie” by her friends, a childhood nickname that had evolved into a winking reference to her slender five-foot-one frame—had arrived in London only weeks before, leaving behind Australia and a husband to whom she was unhappily married. This was her first London party, and it was filled with the kinds of glamorous, intriguing artists and bohemians who she had dreamed would fill her new life.

With the party in full swing, Jessie followed the party’s host, George, around the room. He introduced her to a smattering of acquaintances, before stopping in front of a tall, lean, well-dressed man with a high forehead, thinning brown hair, and a crinkly smile. “This is Flying Captain Bill Lancaster,” George told Jessie. “He’s flying to Australia. That should give you something in common—you ought to get together.”

Lancaster radiated geniality and good cheer, and he was in a chatty mood. In no time at all the handsome pilot was telling Jessie about his plans for an upcoming solo flight to Australia, a feat that had never been attempted with the type of “light” airplane he intended to fly, one that would weigh significantly less than the heavier variety of plane that previous fliers had employed. (In aviation, the terms “heavy” and “light” refer simply to an aircraft’s takeoff weight.) Though the idea had been germinating for some time, Lancaster’s imagination had been newly fired by an event that had electrified the world just one month earlier.

On May 20, 1927, at Roosevelt Field on Long Island, Charles Lindbergh, an unknown U.S. Air Mail pilot, had climbed into his self-designed lightweight aircraft, the Spirit of St. Louis, to begin the first solo nonstop flight across the Atlantic. Thirty-three hours later, an exhausted Lindbergh touched down at Le Bourget Airport in Paris before an ecstatic crowd of more than a hundred thousand spectators. In that instant, Lindbergh’s life, and the world of aviation, were forever changed.

Lindbergh became the most famous man of his day, while aviators themselves became the age’s new idols. In the words of aviatrix Elinor Smith Sullivan, at that time the youngest U.S.-government-licensed pilot on record, “[Before Lindbergh’s flight] people seemed to think we [aviators] were from outer space or something. But after Charles Lindbergh’s flight, we could do no wrong. It’s hard to describe the impact Lindbergh had on people. Even the first walk on the moon doesn’t come close. The twenties was such an innocent time, and people were still so religious—I think they felt like this man was sent by God to do this.” Speaking the month after Lindbergh’s flight, former secretary of state Charles Evans Hughes captured the common mood: “Colonel Lindbergh has displaced everything… He fills all our thought. He has displaced politics… [H]e has lifted us into the upper air that is his home.”

Jessie Miller (Parksfield, 1930)

As Lindbergh biographer Thomas Kessner writes, “It is impossible today to comprehend the scale of his popularity, the void he filled in a bloody era searching for fresh heroes and new departures. War on a scale no one had ever imagined had drained the world of optimism. And in an age desperately searching for a moral equivalent of war, he demonstrated transcendence without menace.” The groundbreaking employment of aircraft in World War I—the first major conflict to feature such large-scale use of flying machines—had proven aviation’s effectiveness as a tool of death and destruction, but Lindbergh recovered its essential thrill. After his record-setting flight, applications in the United States for pilot’s licenses soared, the numbers tripling in the remaining months of 1927 alone. The number of licensed aircraft almost immediately quadrupled, as a long-skeptical public embraced air travel with the fervor of the newly converted.

Though he didn’t mention it to Jessie Keith-Miller at the Baker Street party, Bill Lancaster had witnessed World War I’s atrocities firsthand, from the gory battlefield trenches, and his natural recklessness, combined with his inborn optimism, made him a perfect example of the 1920s breed of flier. With Lindbergh as his model, Lancaster seemed to take it as a given that the flight from England to Australia he envisioned would bring him worldwide fame.

Lancaster’s knowledge of Australia was limited, however, and so, as he chatted with Jessie, he peppered her with questions about her country’s airfields, local routes, and weather. Twelve months earlier Lancaster had left his job as a Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot, and now, at age twenty-nine, with flying jobs growing scarce and a wife and two children to support, he was anxious to make a name for himself. Though Jessie could answer few of his questions, and though she could barely hear him above the noise of the party, Lancaster was positive she could help him simply by virtue of her being Australian. No doubt her impish buoyancy and wide, winning smile added to her considerable appeal. “Come and have tea with me tomorrow at the Authors’ Club at Whitehall,” he urged her. “I’ll show you the plans I’ve made so far.”

The party’s freely flowing alcohol may have enhanced the moment, but Lan- caster’s invitation was a perfect match for Jessie’s own impulsiveness. It was a far cry from the circumscribed nature of her upbringing in a family marked by religious conservatism and Victorian sternness. Her father, Charles Bev- eridge, was a clergyman’s son; her mother, Ethelwyn, a clergyman’s daughter; her uncle ran a parish in Melbourne.

She was born Jessie Maude Beveridge on September 13, 1901, in the tiny western Australia settlement of Southern Cross, little more than a decade after the town’s founding by gold prospectors. Her father had arrived in town four years earlier to manage the local branch of the Commercial Bank, setting up residence in a small apartment above the bank. The year after Jessie another daughter, Eleanor, was born, but, tragically, she died an infant.

In 1905 the Beveridge family moved to Perth, where Jessie’s mother gave birth to a son named Thomas. Here, in the capital city, Jessie and Thomas formed an indissoluble bond, one that grew only more robust with each passing year. When Jessie was seven, the Commercial Bank relocated her father to a branch in the mining town of Broken Hill, halfway across the country, where the family finally bought their own house. Jessie and Thomas attended Convent High School, where Jessie excelled in singing, piano, and music theory. By all accounts she could have had a fine career as a professional musician if she had so chosen.

In 1916 the bank transferred Charles to a new branch in the agricultural town of Timaru, New Zealand. Jessie attended the elite Craighead School, a newly founded private institution dedicated to producing “refined” and “cultured” young women. At Craighead, Jessie was a socially popular star athlete, but just three years later the family moved once again, this time to Melbourne, where Charles worked in the bank’s main office. By this point Jessie had had her fill of relocating—each time the family moved, she had to go through the lengthy and painful process of re-establishing herself and gaining new friends. She also felt oppressed by her family’s staunchly religious lifestyle, which entailed endless visits to church and nonstop Bible reading. For an energetic, audacious spirit like hers, the atmosphere was insufferably claustrophobic. Jessie was keen for an escape.

Bill and Chubbie after arriving in Darwin Mar19,1928 (AP Photo)

At the age of seventeen, Jessie met a Weekly Times journalist named Keith Miller, who was five years older. Though Miller’s personality was far more sober than hers, Jessie, desperate to leave her family, unhesitatingly said yes when Miller proposed to her the following year. The two were married in a Melbourne suburb on December 3, 1919. It soon became apparent, however, that the young couple had little in common. “We were quite maladjusted,” Jessie recalled later in life. “It was like two babies getting married. Our characters were poles apart.” Jessie was headstrong and temperamental, whereas Keith was calm and steady. The quickly apparent gulf between their personalities was exacerbated by an inability to have children: the couple lost one baby born twelve weeks early, and two subsequent miscarriages convinced doctors that Jessie wasn’t fit to bear a child.

Eventually, the couple settled into a rhythm as friends, but they both accepted that they were no longer in love. Keith wanted a traditional wife who would stay at home, whereas Jessie wanted to travel the world and have “the right to live my own life.” She was still itching to break the bonds of her sheltered existence.

Not long after, Jessie’s father passed away from throat cancer at the relatively young age of fifty-seven. Two years later, her beloved brother, Thomas, who had become a midshipman in the navy, died suddenly of cerebral meningitis at age twenty-one. Jessie, caught utterly off guard, was devastated. As children, she and Tommy had spent hours lying on the rug in front of the fireplace, concocting plans to travel the world in search of adventure. He had been her closest confidant, her most intimate sounding board, the person who had kept her sane in the midst of her family’s upheavals and cloyingly pious beliefs. Now her world seemed permanently scarred by misfortune: Tommy and her father were dead, her sister, Eleanor, had died an infant, and Jessie was stuck in a passionless marriage. Emotionally, she was hollowed-out—if not suicidal, then certainly deeply depressed. She felt trapped at the bottom of the world, doomed to wither, barren and alone, beneath the unforgiving Australian sun.

In the throes of her depression, Jessie decided her only option was to find something worth living for—even if she had no idea what that might be. For months she cast around fruitlessly for ideas, until finally a workable plan presented itself. Her father’s family lived in England; at the urging of her aunt, she would go and visit them in an attempt to escape her gloom. Pleading with Keith that the trip was essential to her mental health, Jessie found employment as a door-to-door carpet sweeper saleswoman in order to save up funds for her trip. She even invited Keith to accompany her to England, but he demurred, possibly because his journalism career was well established in Australia. The two may have made a poor married couple, but they were on friendly-enough terms, and Keith agreed to Jessie’s plan: she would live in England for six months while he provided her with a three-pound weekly allowance. He asked only that she earn enough money to pay for her return voyage home.

In the throes of her depression, Jessie decided her only option was to find something worth living for—even if she had no idea what that might be. For months she cast around fruitlessly for ideas, until finally a workable plan presented itself. Her father’s family lived in England; at the urging of her aunt, she would go and visit them in an attempt to escape her gloom. Pleading with Keith that the trip was essential to her mental health, Jessie found employment as a door-to-door carpet sweeper saleswoman in order to save up funds for her trip. She even invited Keith to accompany her to England, but he demurred, possibly because his journalism career was well established in Australia. The two may have made a poor married couple, but they were on friendly-enough terms, and Keith agreed to Jessie’s plan: she would live in England for six months while he provided her with a three-pound weekly allowance. He asked only that she earn enough money to pay for her return voyage home.

The driven, headstrong Jessie made a powerful saleswoman. As one of her customers later recalled, Jessie had knocked on the door of his Melbourne apartment sporting an ear-to-ear grin. When he opened up, Jessie had “thrust a neat, suede-shoed foot between the door and the sash, and refused to remove it until I had agreed to buy a newfangled carpet sweeper that I did not want.” When the customer later spotted Jessie at a club, he asked a female friend who she was. With a knowing smile, the woman replied that Jessie was “a hurricane saleswoman.”

As soon as she had saved up enough money, Jessie, with her devoted friend Margaret Starr in tow, purchased a third-class ticket for the voyage to England. She and Margaret planned to stay in London for six months. When they arrived in the city, in the spring of 1927, they rented a flat and began insinuating themselves into the local community of Australian ex-pats. The freedom and stimulation Jessie had craved for so long were finally hers for the taking.

Now, at the Baker Street party, chatting with Bill Lancaster about his plans to fly to Australia, Jessie had a sudden vision of how she might further change her life.

COREY MEAD is an Associate Professor of English at Baruch College, City University of New York. He is the author of Angelic Music: The Story of Benjamin Franklin’s Glass Armonica and War Play: Video Games and the Future of Armed Conflict. His work has appeared in Time, Salon, The Daily Beast, and numerous literary journals.

The post The Rise and Fall of Aviation’s Golden Couple appeared first on The History Reader.

Powered by WPeMatico