by Stuart E. Eizenstat

For good or ill, Carter’s presidency was foreshadowed by the way he governed in Georgia. He showed his determination to address tough issues by abolishing and combining three hundred state agencies, boards, and commissions into twenty-two. At the same time, he left the necessary backroom bargaining with the state legislature to Bert Lance, his highway commissioner, allowing Carter to avoid the messy political compromises he found distasteful. Bert was all too happy to promise new or repaired roads, highways, and bridges to win over recalcitrant legislators.

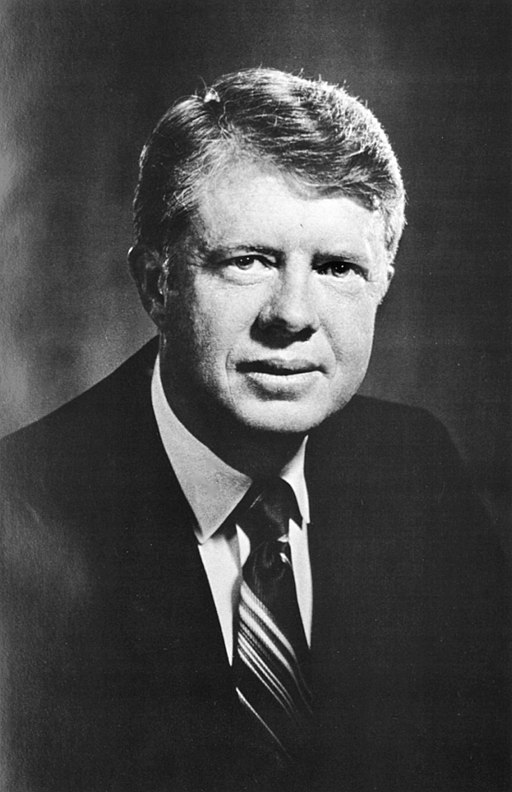

Jimmy Carter in 1971 as Governor of Georgia. Image is in the public domain via Wikipedia.

Carter also showed his commitment to the environment by an unprecedented decision (with shades of the water wars he would fight in Washington) to block the Sprewell Bluff Dam, a job- and park-creating project of the Army Engineers that would have damaged the swamps, streams, and wild rivers Carter prized as God’s creation. No governor in any state had ever blocked a water project fully paid for by the federal government. His willingness to take on vested interests, combined with his stellar civil rights record, made it unlikely that he would have been reelected if the Georgia Constitution had permitted governors to serve two consecutive terms. But Carter was already setting his sights higher than that.

Shortly after his inauguration as governor in January of 1971, the presidency of the United States clearly was coming onto Carter’s personal horizon, although among his cronies and even in the privacy of their fishing trips the only term they used was “national office.” Indeed, Carter was so determined to become president that at the 1972 Miami Democratic Convention, he instructed Ham to start a movement to promote him as Senator George McGovern’s running mate, even though he had been a leader in the anti-McGovern elected officials at the convention. Ham recalled that when they went to Miami they “had this crazy idea of getting Carter on the ticket as VP. We tried to have it both ways. We tried to get on the ticket but not get caught trying.” Chance favored Carter in McGovern’s crushing defeat. He also met Patrick Caddell, McGovern’s brilliant young pollster, just out of Harvard and already a major figure in national Democratic politics—but not to the taste of Kirbo, who recalled that it was “the first time I saw that damn pollster with the long hair.” But gradually the Carter team coalesced into a fighting force with awesome political skills.

Carter’s ambition to gain the presidency was reinforced by measuring himself against the stream of potential candidates who visited him at the governor’s mansion seeking his support. He remembered that “after spending several hours with them drinking beer and so forth, I didn’t see that they were any more qualified than I was… I was amazed at how parochial they were and how narrow-minded they were.” As governor, he had to implement laws they had put through Congress, which Carter said they could barely remember. Still, it seemed presumptuous—even absurd in Ham’s view—for Carter to think or at least talk openly about the presidency until prompted by supporters outside his inner circle. The first formal memorandum came from Dr. Peter Bourne, a physician who had helped draft speeches for Carter’s gubernatorial campaign. With the Vietnam War dragging to a close and Watergate further coloring the voters’ suspicion of Washington, Bourne correctly realized that the forthcoming 1976 presidential campaign might be a time for an outsider with a fresh approach. He wrote Carter a long letter in the summer of 1972, arguing that this was his moment and that he needed to start building a political base. He urged him to travel the country campaigning for Democratic congressional candidates and to write an autobiography; Carter did both.

This sparked a series of meetings in Atlanta throughout the 1972 presidential campaign with Ham, Rosalynn, and his cousin Don Carter, a journalist with Knight-Rider newspapers. The regulars at the mansion joined in. On October 17, Ham started off lightly: “Governor, we have come to talk to you about your future. I don’t know any other way to say this, and it’s hard to bring myself to say the words, but I guess I will just have to say it.” After hesitating for a second, he got it out: “We think you should run for president.” Carter put off his decision until the day after McGovern’s overwhelming defeat. When she realized he intended to run, Rosalynn called his sister Ruth and exclaimed, “ ‘Jimmy’s going to run for p-p-p… ’ I couldn’t even say the word, it was so unreal to me.” On November 5 he convened another meeting of his inner circle at the mansion; they realized they needed a concrete plan, and Carter asked Ham to pull together all the ideas in their recent meetings into one memorandum. The result was Ham’s seventy-two-page outline of his brilliant strategy for catapulting the unknown governor of a medium-sized Southern state to the White House. It became one of the most famous campaign blueprints in modern American political history.

This sparked a series of meetings in Atlanta throughout the 1972 presidential campaign with Ham, Rosalynn, and his cousin Don Carter, a journalist with Knight-Rider newspapers. The regulars at the mansion joined in. On October 17, Ham started off lightly: “Governor, we have come to talk to you about your future. I don’t know any other way to say this, and it’s hard to bring myself to say the words, but I guess I will just have to say it.” After hesitating for a second, he got it out: “We think you should run for president.” Carter put off his decision until the day after McGovern’s overwhelming defeat. When she realized he intended to run, Rosalynn called his sister Ruth and exclaimed, “ ‘Jimmy’s going to run for p-p-p… ’ I couldn’t even say the word, it was so unreal to me.” On November 5 he convened another meeting of his inner circle at the mansion; they realized they needed a concrete plan, and Carter asked Ham to pull together all the ideas in their recent meetings into one memorandum. The result was Ham’s seventy-two-page outline of his brilliant strategy for catapulting the unknown governor of a medium-sized Southern state to the White House. It became one of the most famous campaign blueprints in modern American political history.

Watch the official book trailer for President Carter: The White House Years

STUART E. EIZENSTAT has served as U.S. Ambassador to the European Union and Deputy Secretary of both Treasury and State. He is the author of Imperfect Justice and President Carter. He is an international lawyer in Washington, D.C.

The post President Carter: The White House Years appeared first on The History Reader.

Powered by WPeMatico