by Arnold van de Laar

When Erik Weisz died on 31 October 1926, it was world news. Like Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, Erik Weisz typified the spirit of that wonderful time in America. Almost no one knew his real name but his stage name is still—almost a century later—known around the world and has become synonymous with the art that he developed. Erik Weisz was the world-famous Harry Houdini, the escape artist who had himself buttoned up into a straitjacket and hoisted up in the air by his feet, wrapped in chains and sealed in a wooden chest and then thrown overboard in New York harbor, handcuffed and shut in a milk churn full of beer. And he always emerged unharmed, even after being buried alive in a bronze coffin. Many will think that his death was as spectacular as his life, that he drowned while performing his legendary Chinese Water Torture Cell act—handcuffed, upside down and underwater, on stage, in front of a packed theatre. But nothing is further from the truth.

Houdini ornamented his spectacular escape acts with Spiritism and classical circus tricks. He was a juggler, an acrobat and a strong-man. He claimed, for example, that his abdominal muscles could withstand any blow and challenged everyone to try it out. For a long time, it was assumed that his death had been caused by one of these hefty punches in his stomach, but we know now that it had nothing to do with his stunts and was largely down to his stubborn refusal to go to a doctor.

Gordon Whitehead, Jacques Price and Sam Smilovitz were three Canadian students. They visited Houdini in his dressing room in the theatre in Montreal on 22 October 1926, the morning after his performance. Houdini lay on a divan to pose for Smilovitz, who wanted to draw a portrait of him. Whitehead asked him if it was true that he could withstand any blow to his stomach and whether he could give it a try. Houdini agreed and the student immediately started to punch him. He hit Houdini several times extremely hard in his right lower abdomen. The two other young men later stated that the escape artist was clearly not ready for their friend’s rapid attack. They saw that he had only been able to tense his abdominal muscles sufficiently after the third blow and they noticed that, as the tough escape artist—who had been so magnificently indestructible on the stage the previous night—lay there on the divan, he seemed to be suffering unexpected terrible pain from the few well-aimed punches.

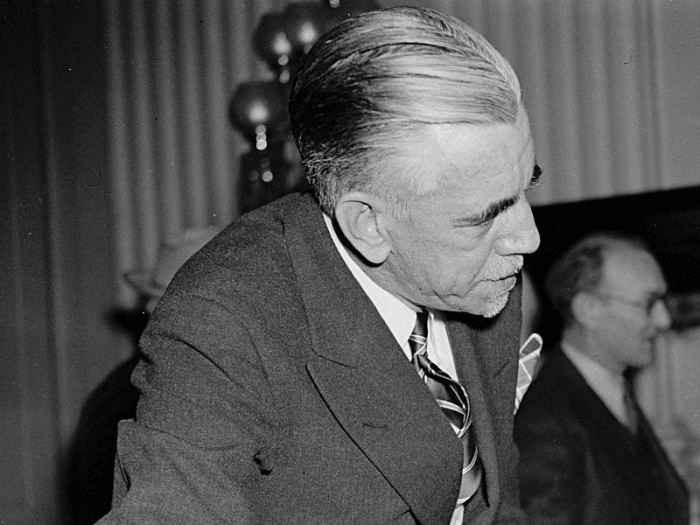

Harry Houdini, circa 1905. Image is in the public domain via Wikipedia.

Houdini left the following day, after his evening show, taking the train to Detroit, the next stop on his tour. He was not feeling well and sent a telegram ahead asking to see a doctor when he arrived. But once he got to the city, he had no time to be examined and started the final performance of his life with a high fever. He may have performed his underwater escape act, which entailed him holding his breath for several minutes—a fantastic achievement considering that, after the show, a doctor had no hesitation in concluding that he needed to be operated on immediately. The audience thus had no idea just what an incredible stuntman they were watching up there on the stage.

The surgeon at the hospital in Detroit made his diagnosis with a simple physical examination. Laying his hand on Houdini’s abdomen, he declared that the escape artist was suffering from an everyday complaint—appendicitis—but which was only just then starting to be understood. It had only been correctly described for the first time forty years earlier (when Houdini was twelve years old) by Reginald Fitz in Boston. That is remarkable for a life-threatening illness that must have been affecting people for thousands of years. There is no mention of it in ancient Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek or Roman medical texts, while it must have been prevalent in these old civilizations, where knowledge of medicine was already quite advanced. It was first described by Giovanni Battista Morgagni, an eighteenth-century anatomist, but he too was unable to put his finger on the correct cause of its lethal consequences. Only in 1887 did it become clear that this illness did not have to end in the death of the patient when Dr. Thomas Morton in Philadelphia conducted the first successful operation to treat it.

Houdini should, therefore, have simply gone to the hospital in Montreal, where he could have been saved by an operation. Was he too stubborn, too vain, too money-driven, or simply afraid of doctors? He probably thought ‘the show must go on’. Consequently, he was not operated on until three days later in Detroit. The surgeon discovered peritonitis, which develops from the bursting of the appendix. Houdini’s abdominal cavity was completely infected with pus. Four days later his abdomen had to be opened up again to be rinsed out. But the situation did not improve and there were at that time no antibiotics to fight the infection.

Harry Houdini died two days later, at the age of fifty-two. He was buried in Queens, New York, amid a whirl of public attention, in the same bronze coffin he had used for his escape acts. Erik Weisz, juggler, stuntman, Spiritist and, above all, escape artist—known around the world as The Great Houdini—died of a banal, everyday complaint: appendicitis.

Appendicitis is a very common disease. More than 8% of men and almost 7% of women contract appendicitis at some time in their lives. It can occur at any age and is the most common cause of acute abdominal pain. The appendix—more correctly the vermiform (‘worm-shaped’) appendix—is a blind-ended intestinal tube starting from the great bowel near the junction with the small bowel, located in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. It is less than a centimeter in diameter and some ten centimeters long.

Doctors knew about the small organ for a long time, but it had never occurred to anyone that such a small thing could have such disastrous consequences. It is because it is so small that, once it is inflamed, it can burst quite quickly. The contents of the intestines are then released into the abdomen, which causes peritonitis, inflammation of the entire peritoneum, the lining of the abdominal cavity. And that is why the link was never made between that small appendix and the fatal consequences of an abdominal inflammation. Before surgeons dared to open up a living patient’s abdomen with any degree of success in the nineteenth century, they only saw the final state of the appendix in the body of the deceased. During the autopsy, amid the debris of full-scale peritonitis, no one had ever noticed the rupture of that tiny, worm-shaped appendage.

Appendicitis generates a typical series of symptoms that reflect the successive stages of the disease, starting with the inflammation of the appendix itself. This causes a vague organic pain in the center of the upper abdomen. Within a day, the inflammation expands around the appendix and starts to irritate the peritoneum in the area where it is located, on the right side of the lower abdomen. This local pain is much more acute and pronounced than the vague organic pain. Typically, patients with appendicitis describe the pain as moving downwards from the center to the lower right of the abdomen, increasing in severity as it does so. The local irritation of the peritoneum also causes fever, loss of appetite (anorexia) and, above all, pain during movement. Patients can no longer tolerate being touched or making sudden movements, and prefer to lie still, flat on their backs with their legs pulled up. For a normal person in this stage of the disease, it would seem impossible to remain standing in front of a theatre full of people, not to mention allow themselves to be tied up, hung upside down and immersed in the Chinese Water Torture Cell as Houdini did.

Pus then forms around the appendix. At first, the pus can be contained by the surrounding intestines, but in the next stage the appendix dies off locally and bursts. Feces and intestinal gases are then released into the abdominal cavity. The patient experiences a sudden increase in the pain in the lower right of the abdomen, which then spreads throughout the whole abdomen and becomes so severe that it is no longer possible to say exactly where it is coming from. This is the stage of life-threatening peritonitis.

The total picture that fits in with peritonitis is typically that of an ‘irritated abdomen’. The abdominal muscles are tense, the abdomen is hard and every movement is painful. It is not only painful when the abdomen is touched, but even more so when it is released—this is known as ‘rebound tenderness’. The patient’s face is pale, anxious and tense, with sunken eyes and cheeks. The intestines in the abdomen respond to the inflammation by stopping their normal movements. Through a stethoscope, the abdomen is unnaturally quiet. All of these symptoms are so typical of peritonitis that it can be diagnosed in a couple of seconds, with a quick look at the patient (face and position), a few questions (where does it hurt and where and when did it start?), pressing the abdomen once (hard and painful when pressure is applied and released) and listening with the stethoscope (no audible intestinal movements). In the final stage, the patient experiences septic shock caused by blood poisoning; the peritoneum has a large surface area, allowing a mass release of bacteria into the bloodstream. That leads to general poisoning of the body, causing high fever and affecting all organs, with death as the result.

Peritonitis is an acute surgical emergency. The surgeon has to repair or remove the cause as soon as possible and rinse the abdominal cavity. This should be done at the earliest stage possible, preferably before the onset of septic shock or, even better, before the stage of general peritonitis, but the best time is while the problem is still restricted to the affected organ, the tiny appendix. Acute appendicitis is therefore already a surgical emergency.

In 1889, American surgeon Charles McBurney described these principles for operating on appendicitis, namely the sooner the operation is performed, the greater the chances of a full recovery, and that it is sufficient to remove the inflamed organ as long as peritonitis has not yet developed. This linked McBurney irrevocably to appendicitis. The spot on the abdomen where the most pain usually occurs is known as McBurney’s point and the incision in the abdominal wall to perform the appendectomy is also named after him. Every surgeon knows immediately what the problem is if a colleague says that a patient has ‘tenderness at McBurney’s point’.

A classical operation for appendicitis proceeds as follows. The patient lies on his back, the surgeon standing to his right and the assistant to the left. The surgeon makes a small, diagonal incision in the lower right of the abdomen, at McBurney’s point, which is exactly two-thirds of the way down an imaginary line between the navel and the bony projection of the iliac crest, the outer edge of the pelvis. There, beneath the skin and the subcutaneous tissue, are three abdominal muscles on top of each other. At exactly this point in the abdominal wall, these muscles can be passed without cutting them, by maneuvering between the muscle fibers, as though you are opening three pairs of curtains. Below the third muscle is the peritoneum. You have to take hold of this carefully and open it up, making sure you do not damage the intestines. If you are lucky, you can now see the appendix but, usually, it is hidden away somewhere in the depths of the abdomen. You can feel around for it with your finger, free it carefully and pull it outwards. Using a small clamp and an absorbable thread, you first divide and tie off the blood vessel feeding the appendix. You then do the same with the appendix itself. You can now close the peritoneum, move the muscles back in place, and close the aponeurosis, the flat tendon of the outermost of the three abdominal muscles. Lastly, you close the subcutaneous tissue and the skin. The whole business takes about twenty minutes. Today, however, the appendix is no longer removed using the classical procedure. Now, a laparoscopic appendectomy is preferred, using keyhole surgery via the navel and two very small incisions.

Houdini’s symptoms were typical of appendicitis—fever and pain in the lower right of the abdomen. The doctor who was only permitted to examine him in his dressing room in Detroit after the show encountered a seriously sick man with an irritated lower right abdomen. The symptoms were so obvious that the doctors did not even consider the punch in the stomach that Gordon Whitehead had given Houdini three days previously. The diagnosis was confirmed during the operation – they found a perforated appendix and the consequential peritonitis. And yet, it was the punches to the stomach that were the focus of attention later. Other cases of alleged ‘traumatic appendicitis’ – that is, caused by a direct blow, fall or other trauma to the abdomen—were cited. No causal link has, however, ever been found between trauma and appendicitis, and the fact that these two events occurred within days of each other must be seen as coincidence. Nevertheless, the cause of appendicitis is by no means always clear. We do not know why some people contract appendicitis at a certain moment, while others never do.

Harry Houdini and his wife Beatrice. Image is in the public domain via Wikipedia.

In the case of Houdini, it was apparently important to find a cause. The three students were extensively interrogated by the police and the punch delivered by poor Gordon Whitehead was established as the clear cause of death. It may have also been significant that Houdini, given his not entirely danger-free profession, had taken out life insurance that included an accident clause. The clause stated that his wife and lifelong assistant Bess Weisz would receive a double pay-out—500,000 dollars—if Houdini died as the result of an accident while performing a stunt.

While a punch in the stomach to demonstrate his strength could be considered as such, an everyday disease like appendicitis of course could not. Fortunately, Whitehead was not prosecuted for grievous bodily harm or manslaughter, as Price and Smilovitz were able to testify that Houdini had given him permission to punch him.

Among the audience at Houdini’s last performance in the Garrick Theater in Detroit on 24 October 1926 was a man called Harry Rickles. He later recalled that the show had been a disappointment. It had started more than half an hour late and Houdini did not look well. He made mistakes, so that the audience could see through his tricks, and he had to be supported by his assistant several times. But when Rickles read that the escape artist had performed with a burst appendix, from which he died several days later, he realized that Houdini had given his life to perform for his admirers right up to the last minute.

ARNOLD VAN DE LAAR is a surgeon in the Slotervaart Hospital in Amsterdam, specializing in laparoscopic surgery. Born in the Dutch town of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, van de Laar studied medicine at the Belgian University of Leuven before taking his first job as general surgeon on the Caribbean Island of Sint Maarten. He now lives in Amsterdam with his wife and two children where, a true Dutchman, he cycles to work every day. Under the Knife is his first book.

The post The Death of an Escape Artist: Harry Houdini appeared first on The History Reader.

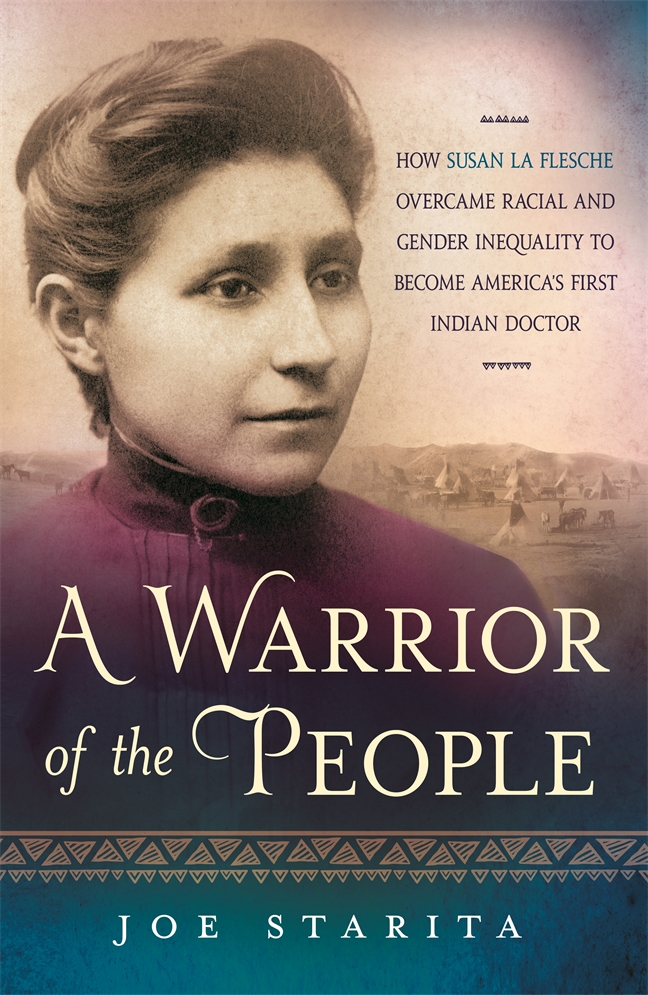

If Susan sought cultural sustenance and inspiration in the hallways of the local Indian orphanages and boys’ homes, her attentions were reciprocated. Not long into her medical studies, her name began to crop up in Indian school publications and conversations, a name increasingly held up as a motivational tool, a role model for others to aspire to. Soon after the joint band concert, Susan described the reaction she got from some of the younger Omaha students. “I think they must have been so glad to see me and I think my graduation honors at [Hampton] must have made them feel so proud of me,” she told Rosalie. The Carlisle school newspaper described her as one of Hampton’s most gifted students, and most of their students knew she had received the gold medal and finished second in her graduating class.

If Susan sought cultural sustenance and inspiration in the hallways of the local Indian orphanages and boys’ homes, her attentions were reciprocated. Not long into her medical studies, her name began to crop up in Indian school publications and conversations, a name increasingly held up as a motivational tool, a role model for others to aspire to. Soon after the joint band concert, Susan described the reaction she got from some of the younger Omaha students. “I think they must have been so glad to see me and I think my graduation honors at [Hampton] must have made them feel so proud of me,” she told Rosalie. The Carlisle school newspaper described her as one of Hampton’s most gifted students, and most of their students knew she had received the gold medal and finished second in her graduating class.

As the Case Agent of the UCO, I would be managing everything from behind the scenes. I also needed people to help me with logistics and the enormous amount of FBI paperwork that would be generated. From our Squad, I selected a young African American FBI Special Agent named Hank Roberts, whom I had just finished training to be my #2, and another Squad Agent named Wayne Kent, to be the admin guy. (More on Kent later.)

As the Case Agent of the UCO, I would be managing everything from behind the scenes. I also needed people to help me with logistics and the enormous amount of FBI paperwork that would be generated. From our Squad, I selected a young African American FBI Special Agent named Hank Roberts, whom I had just finished training to be my #2, and another Squad Agent named Wayne Kent, to be the admin guy. (More on Kent later.)

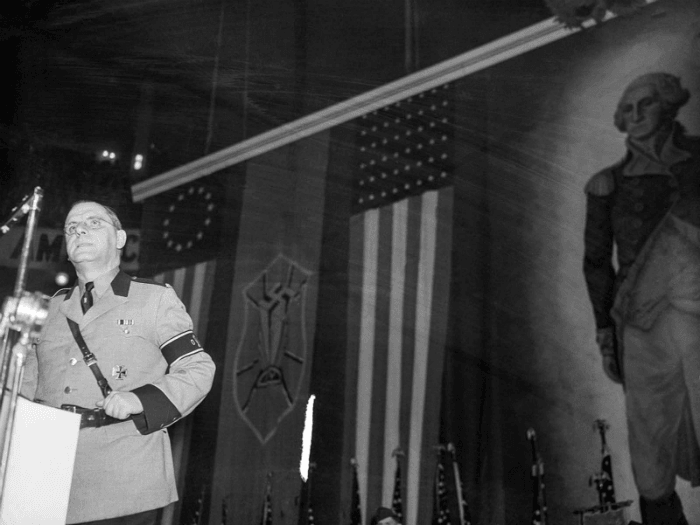

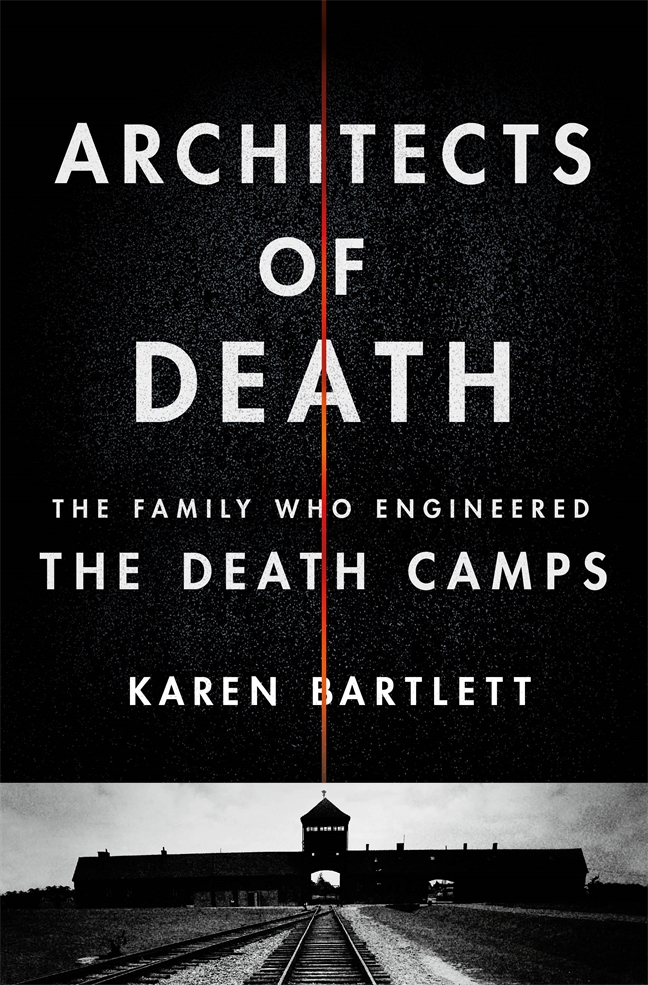

muffle ovens to meet the demands of the SS at Auschwitz, where Nazi administrators calculate that Soviet prisoners will die at a rate of 1,000 per day.

muffle ovens to meet the demands of the SS at Auschwitz, where Nazi administrators calculate that Soviet prisoners will die at a rate of 1,000 per day.