by Lucy Worsley

Drawing from the vast collection of Victoria’s correspondence and the rich documentation of her life, author Lucy Worsley recreates twenty-four of the most important days in Victoria’s life. Each day gives a glimpse into the identity of this powerful, difficult queen and the contradictions that defined her. Queen Victoria is an intimate introduction to one of Britain’s most iconic rulers as a wife and widow, mother and matriarch, and above all, a woman of her time. Keep reading for an excerpt.

* * * * *

‘I will be good’: Kensington Palace, March 11, 1830

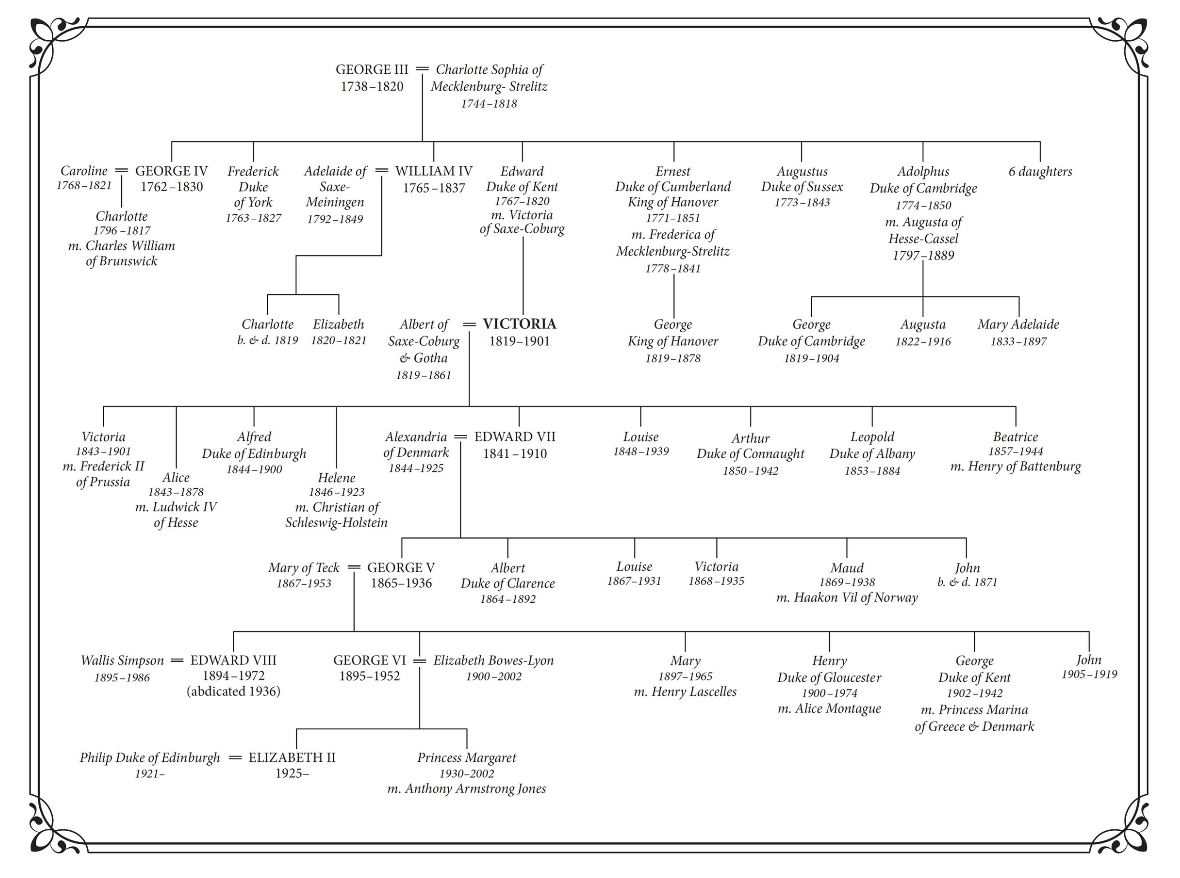

Her teacher hands her a book. Folded within its pages is a chart listing Britain’s kings and queens. Victoria, in her white dress and coral necklace, has pretty light brown hair and a chubby lower lip that tends to fall open unless she remembers to keep it closed. She’s just short of eleven years old. The knowledge of her place in the succession has so far been kept from her. Look at the chart, she is told. Her uncle the king George IV is gravely ill. He cannot live long. Who will come next?

What follows is one of the best-known and most dramatic scenes in Victoria’s life. Sitting at the rosewood table in Kensington Palace where she did her lessons, she studied the chart, thought it through and worked it out. When her oldest uncle George died, her next oldest uncle William would take over. And when he died, she must herself become queen.

‘I see I am nearer the throne than I thought,’ Victoria is supposed to have said. ‘I will be good!’

‘I see I am nearer the throne than I thought,’ Victoria is supposed to have said. ‘I will be good!’

It would become the most celebrated statement of Victoria’s childhood, rousing words, with a message of responsibility and duty: one must step up to the challenge of ruling one’s country, as well as learning one’s French.

But did it really happen?

One detail at least is agreed by all sources: that the setting was Kensington Palace. It was the sleepiest and most sedate of the numerous royal palaces. Kensington was ‘a place to drink tea’, by contrast to Windsor Castle – ‘a place to receive monarchs’ – and Buckingham Palace, where you went ‘to see fashion’. During Victoria’s Kensington childhood, anyone going for a walk ‘quietly along the gardens, fancies no harsher sound to have been heard from the Palace windows, than the “tuning of the tea-things”’, or the playing of a piano.

Behind closed doors, though, the atmosphere at Kensington was far from peaceful. Victoria would come to believe it was not so much a palace as a prison. Deep in the gardens, she was growing up in isolation. Her guardians deliberately kept her well away from both the greedy eyes of her future subjects, and the disreputable, high-society world of George IV. She was comfortable, she was well-fed, she had toys. But she was also under considerable psychological strain. She formed the center of a small and close-knit circle whose adoration placed her under what was sometimes intolerable pressure.

Into this pressure-cooker of adulation came the bracing influence of Johanna Clara Louise Lehzen. She’d arrived at Kensington in 1819 as Feodore’s governess. Five years later, Victoria was old enough to need a governess of her own. Prince Leopold, still giving financial help to his sister’s household, decided that Lehzen should do the job. Although he did not live at Kensington, his influence was very great. Victoire had £6,000 a year, voted by Parliament at the time of her marriage. Leopold, though, had £50,000 annually, a wildly generous provision made at the time of his short-lived marriage to the late Princess Charlotte. The wider royal family considered that Leopold could easily bear some of the living costs of his sister and niece. Yet leaving Leopold to shoulder the financial responsibility like this meant that the royal family also sacrificed a good deal of their own power over Victoria. Because he paid for things, Victoria would become almost the property, indeed the puppet, of her beloved ‘Uncle Leopold’.

And Leopold now chose Lehzen. This was partly because he thought she would be a counter-influence against Captain Conroy, who controlled much of what went on at Kensington, and whom Leopold distrusted. ‘Lehzen’, as the household called her, was an intense character, with dark-eyed, dark-haired ‘Italian’ looks, and a disordered digestion. She’d say that she ‘did not know the feeling to be hungry’ – something that would later cause trouble with her pupil – and that all she ever ‘fancied were potatoes’. She suffered from migraines, which some people misinterpreted as a drinking problem. It was family tragedy that had forced Lehzen to find work as a governess. She was the youngest daughter of a pastor in Hanover; her mother had died when she was young, and three of her sisters had also passed away before reaching twenty. Lehzen was born the wrong side of the scenes to sit down at table with aristocrats and courtiers, and was eventually made a baroness to eliminate the difficulties in etiquette that this caused.

Lehzen had the self-discipline, plus the selfless dedication, that her position demanded. But she considered the job offer that Leopold made (via Victoire) very carefully before accepting. ‘After a short silence,’ Lehzen recollected of the interview, ‘I said that I had often thought of the great difficulties which such a person might have to encounter in educating a Princess. As a condition of her service, Lehzen asked that she might always be present when Victoria met third parties, so that her influence would be paramount. Although Victoria met few outsiders, this did not mean that she spent much time alone. Every aspect of her progress through girlhood was kept constantly under watch. ‘I never had a room to myself,’ Victoria claimed in later life, ‘till I was nearly grown up always slept in my Mother’s room.’ Victoria told one of her own children that she was not even allowed to walk downstairs unaccompanied in case she fell. Even when she walked out in Kensington Gardens, the young princess felt, people constantly ‘look at me … to see whether I am a good child’.

As she was already living at Kensington Palace, Lehzen must have been aware that her charge would be difficult to manage. The celebrated fiery temper of the Hanoverian dynasty was already visible in the little girl: people called her ‘le roi Georges in petticoats’. ‘Did she not feel unhappy when she had done wrong?’ a tutor once asked her. ‘Oh no,’ Victoria replied. Her mother Victoire was still finding all this very difficult. Her younger daughter ‘drives me at times to real desperation’, she admitted.

Victoire watched Victoria so closely and carefully because of the legitimate fear that despite her late husband’s will, George IV might at any time try to remove her daughter from her care. Previous kings had always made their own educational arrangements for their heirs, and precedent was everything in the royal family. George IV’s personal dislike of Victoire meant he was constantly ‘talking of taking her child from her’.

The lonely Victoire, with her debts and responsibilities and grief, was scatterbrained and prone to making poor judgments of character. But she redeems herself with her charm and warmth, and clearly loved her children. ‘Her kindness and softness,’ it was said of her, ‘are very delightful in spite of want of brains.’ She was gradually learning the language of her adopted country, but still apologized to visitors ‘for not speaking English well enough to talk it’. This is one of the reasons she had grown so dependent upon Captain Conroy.

Victoire never wrote – nor presumably spoke – quite as a native. Did she, therefore, talk to her daughter in German? The unpopularity of the German Hanoverians in Britain explains Victoria’s own later insistence that she did not. ‘Never spoke German … not allowed to,’ she stoutly claimed. Her schoolroom timetable does reveal, however, that she had a formal German lesson twice a week. And the German accents of Victoria’s mother, Lehzen and Späth did certainly affect her spoken English. Her tutor Mr. Davys, brought in to supplement Lehzen with more formal lessons, recollected that at first ‘she confused the sound of the “v” with that of “w”, and pronounced much as muts.’

It must have been hard for Victoire when her own daughter began to talk about ‘my angelic dearest Mother, Lehzen, who I do so love!’ But a coldness was gradually creeping into Victoire’s relationship with Victoria, not least because Victoria had picked up on her Uncle Leopold and Lehzen’s distrust of Captain Conroy. ‘I have grown up all alone,’ Victoria later declared. This was not technically true; it was more that she felt alone. In reality, she was constantly surrounded not only by servants but also, as time went on, by Conroy’s family. His wife was a frequent visitor, and his daughters, Jane and another Victoire, became Victoria’s approved playmates. With them, she played with rudimentary jigsaws called ‘dissected prints’, made cottages out of cards, dressed up as ‘Nuns’ or ‘Turks’ or rode upon a pony called Isabel. It doesn’t sound like a lonely life, but the loneliness that she experienced stemmed from the fact that her intimates were chosen for her.

Conroy, for his part, had insinuated himself completely into Victoire’s confidence. It’s clear that he was adept at exploiting her lack of self-belief. ‘So often, so very often,’ she confessed to him, ‘what you said so often and what hurt me, but unhappily is true, I am not fit for my place, no, I am not. – I am just an old stupid goose.’ Victoire also worried that Conroy had appointed a rather dubious clerk to pay the palace bills. She later admitted that ‘she was afraid of him – he might be dishonest’. Victoire’s own vagueness confused and irritated Conroy in return. ‘The Duchess lives in a mist,’ he said, ‘and therefore she is very difficult to deal with.’

By early 1830, when Victoria was ten, it was clear that George IV – blind, obese, addicted to laudanum and hiding away at Windsor – was dying. Lehzen has left a description of her pupil in early adolescence. ‘My Princess,’ as Lehzen calls her, ‘is not tall, but very pretty, has dark blue eyes, and a mouth which, though not tiny, is very good-tempered and pleasant, very fine teeth, a small but graceful figure, and a very small foot.’59 Victoria’s minuscule feet were well displayed in the pretty, flat, ribboned pumps of contemporary fashion. At the age of fifteen, her foot would be 21.3 centimeters long, making her, in modern terms, a British size two.

By early 1830, when Victoria was ten, it was clear that George IV – blind, obese, addicted to laudanum and hiding away at Windsor – was dying. Lehzen has left a description of her pupil in early adolescence. ‘My Princess,’ as Lehzen calls her, ‘is not tall, but very pretty, has dark blue eyes, and a mouth which, though not tiny, is very good-tempered and pleasant, very fine teeth, a small but graceful figure, and a very small foot.’59 Victoria’s minuscule feet were well displayed in the pretty, flat, ribboned pumps of contemporary fashion. At the age of fifteen, her foot would be 21.3 centimeters long, making her, in modern terms, a British size two.

It was George IV’s impending death that eventually made it clear that the truth of Victoria’s position must be revealed to her. William, Duke of Clarence, and his wife Adelaide (from the double wedding at Kew) were next in line to reign. But the tragic early deaths of their four children meant that when William took the crown, Victoria would become his heir presumptive. This she needed to know.

There are two rival accounts, Lehzen’s and Mr. Davys’s, of how she learned of her future fate, and 11 March 1830 is the most likely date. Yet each witness has a self-serving desire to claim the honor of having announced her destiny to the little girl, and their accounts are incompatible.

Mr. Davys later told his son that he had been the one to reveal her future to Victoria. During lessons, he says, he had ‘set her to make a chart of the kings and queens. She got as far as “Uncle William”, before coming to a stop.’ Who, Mr. Davys asked, was the next heir to the throne? ‘She rather hesitated, and said, “I hardly like to put down myself.”’ According to Lehzen, though, it was she, not Mr. Davys, who slipped a ‘chronological table’ of the kings and queens of England into Victoria’s history book. Possibly this was a well-known teaching aid called ‘Howlett’s Tables’. ‘When Mr. Davys was gone,’ Lehzen reminisced, years later, ‘Princess Victoria opened, as usual, the book again and seeing the additional paper said: “I never saw that before.”’

‘It was not thought necessary you should, Princess,’ Lehzen answered.

‘I see I am nearer to the Throne than I thought,’ Victoria declared. Lehzen next produces a record of a speech that is quite frankly implausible for a little girl. ‘Many a child would boast,’ Victoria is supposed to have said, ‘but they don’t know the difficulty; there is much splendor, but there is more responsibility!’

In Lehzen’s sentimental – and highly Victorian – version of the scene, Victoria then raised her right forefinger, as if making an oath. She ‘gave me that little hand’, Lehzen continued, saying the words that everyone remembers.

‘I will be good!’ the princess promised.

It seems too good to be true, a parable told by a fond governess that shows both teacher and pupil in the best possible light. Yet Victoria, reading this account years later, certainly recollected that something along those lines had indeed occurred. She noted her own memory of the day in the margin of Lehzen’s account: ‘I cried much,’ she records, on learning that she would be queen, ‘and ever deplored this contingency.’

On 13 March 1830, Victoire reported to the Bishop of London that her daughter knew all, and that there had been no stage management by Lehzen or Davys and their family trees and exhortations. ‘What accident has done,’ Victoire wrote, ‘I feel no art could have done half so well … we have everything to hope from this Child!’

And Victoire gains credibility as a witness if you look at the dates on which the various accounts were written. Lehzen’s and Davys’s were set down years later, deep into Victoria’s reign, when each was eager to claim a legacy in the formation of her character. I think that we have, after all, to trust the daffy duchess’s account from just two days after the event, and accept that one of the most dramatic scenes in Victoria’s life – ‘I will be good!’ – was merely dramatic license.

The Duchess of Kent’s educational arrangements also had another advantage. Victoria’s curious upbringing, despite the strain it placed upon her, despite her hostility to Captain Conroy, would turn out to be an excellent strategy in terms of public relations. Her childhood seclusion meant that she could, in due course, be presented to her people as a most interesting young lady.

The most interesting young lady, in fact, that the world contained.

Interested in more from Lucy Worsley? Listen to an excerpt of the Queen Victoria audiobook:

LUCY WORSLEY is a historian, author, curator and television presenter. Lucy read Ancient and Modern History at New College, Oxford and worked for English Heritage before becoming Chief Curator of Historic Royal Palaces. She also presents history programs for the BBC and is the author of several bestselling books, including Courtiers: the Secret History of the Georgian Court, Cavalier: The Story of a 17th Century Playboy, and more. She lives in London, England.

The post Queen Victoria: Twenty-Four Days That Changed Her Life appeared first on The History Reader.

Powered by WPeMatico

In 2014 and during the presidential campaign, activists compelled the media to resurrect many of the dead victims of police violence as full human beings, their deaths recorded on YouTube and debated at political conventions.

In 2014 and during the presidential campaign, activists compelled the media to resurrect many of the dead victims of police violence as full human beings, their deaths recorded on YouTube and debated at political conventions.

I sipped an amber rum. Habana Club. Seven years. No ice. He palmed a Bucanero beer, half wrapped in a flimsy white paper napkin. Curls of Cohiba smoke wafted between us, giving the room a translucent look and an acrid taste. Castro was having a drink. And so was I. It was a Friday evening in late November 2010, and we were ensconced on opposite ends of a small subterranean saloon on the western outskirts of Havana. It was my last night in Cuba.

I sipped an amber rum. Habana Club. Seven years. No ice. He palmed a Bucanero beer, half wrapped in a flimsy white paper napkin. Curls of Cohiba smoke wafted between us, giving the room a translucent look and an acrid taste. Castro was having a drink. And so was I. It was a Friday evening in late November 2010, and we were ensconced on opposite ends of a small subterranean saloon on the western outskirts of Havana. It was my last night in Cuba.

The

The

Meanwhile, Rao keeps looking for more, as do competing scientists from Europe and North America. Of course, they are not alone: with the high price tag as an indication of potential compensation for illicit trafficking of Yunnan box turtles, poachers are motivated to be out in force around the province seeking one of the rarest turtle species in the world – not for science but for profit.

Meanwhile, Rao keeps looking for more, as do competing scientists from Europe and North America. Of course, they are not alone: with the high price tag as an indication of potential compensation for illicit trafficking of Yunnan box turtles, poachers are motivated to be out in force around the province seeking one of the rarest turtle species in the world – not for science but for profit.

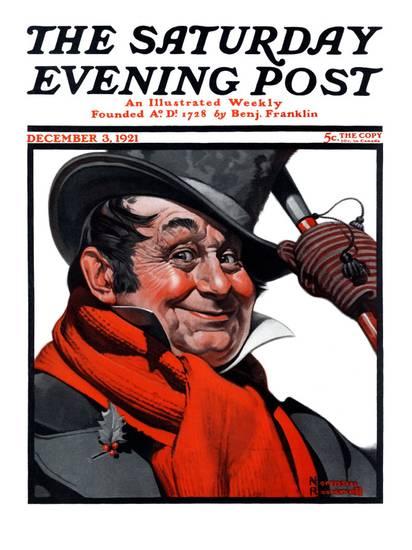

Judith Waggoner writes that “After the shock of World War I, people craved the comfort of more innocent times. They found it in the world of Charles Dickens. There were four different film versions of A Christmas Carol to choose from, and magazine covers of the era often depicted scenes with the flavor of merry old England.” The “old English” sort of Christmas, by the way, never really existed in America; U.S. Puritan heritage has been decidedly opposed to Christmas merrymaking. Thus, the pseudo-Dickensian yuletide of the 1920s amounted to pure nostalgic fantasy. This nostalgia translated into decorations with carriage lantern and antique candle holder motifs, and Victorian-style paper silhouettes, while English holly, rather than today’s pine boughs, were the favored holiday greenery. (In fact, in my home region of Western Washington State, holly planted in the 1920s as a holiday cash crop is now considered an out-of-control invasive species.) In keeping with that pseudo-Dickensian theme, Norman Rockwell’s cover for The Saturday Evening Post’s December 3, 1921 issue depicts a ruddy-cheeked coachman in a Victorian top hat and collar, with holly on his lapel. Similarly, Rockwell’s December 8, 1928 cover shows a man and woman in mid-nineteenth-century attire dancing beneath the mistletoe. They, too, are ruddy-cheeked. Must be something in the punch.

Judith Waggoner writes that “After the shock of World War I, people craved the comfort of more innocent times. They found it in the world of Charles Dickens. There were four different film versions of A Christmas Carol to choose from, and magazine covers of the era often depicted scenes with the flavor of merry old England.” The “old English” sort of Christmas, by the way, never really existed in America; U.S. Puritan heritage has been decidedly opposed to Christmas merrymaking. Thus, the pseudo-Dickensian yuletide of the 1920s amounted to pure nostalgic fantasy. This nostalgia translated into decorations with carriage lantern and antique candle holder motifs, and Victorian-style paper silhouettes, while English holly, rather than today’s pine boughs, were the favored holiday greenery. (In fact, in my home region of Western Washington State, holly planted in the 1920s as a holiday cash crop is now considered an out-of-control invasive species.) In keeping with that pseudo-Dickensian theme, Norman Rockwell’s cover for The Saturday Evening Post’s December 3, 1921 issue depicts a ruddy-cheeked coachman in a Victorian top hat and collar, with holly on his lapel. Similarly, Rockwell’s December 8, 1928 cover shows a man and woman in mid-nineteenth-century attire dancing beneath the mistletoe. They, too, are ruddy-cheeked. Must be something in the punch. Christmas Dinner: No.1: Oyster Cocktails in Green Pepper Shells, Celery, Ripe Olives, Roast Goose with Potato Stuffing, Apple Sauce, String Beans, Potato Puff, Lettuce Salad with Riced Cheese and Bar-le-Duc French Dressing, Toasted Wafers, English Plum Pudding, Bonbons, Coffee. No.2: Cream of Celery Soup, Bread Sticks, Salted Peanuts, Stuffed Olives, Roast Beef, Yorkshire Pudding, Potato Soufflé, Spinach in Eggs, White Grape Salad with Guava Jelly, French Dressing, Toasted Crackers, Plum Pudding, Hard Sauce, Bonbons, Coffee.

Christmas Dinner: No.1: Oyster Cocktails in Green Pepper Shells, Celery, Ripe Olives, Roast Goose with Potato Stuffing, Apple Sauce, String Beans, Potato Puff, Lettuce Salad with Riced Cheese and Bar-le-Duc French Dressing, Toasted Wafers, English Plum Pudding, Bonbons, Coffee. No.2: Cream of Celery Soup, Bread Sticks, Salted Peanuts, Stuffed Olives, Roast Beef, Yorkshire Pudding, Potato Soufflé, Spinach in Eggs, White Grape Salad with Guava Jelly, French Dressing, Toasted Crackers, Plum Pudding, Hard Sauce, Bonbons, Coffee.