by Maia Chance

In 1921, Frances Lester Warner described a Christmas Eve scene in Boston with “red and white crystal” in shop windows, “lights gleaming on the slippery cross-streets, throngs of last-minute shoppers” and “bright posters still cheerfully advising us to do our shopping early.” She wrote of a “tall Santa Claus, bearded and red-cheeked, scarlet-coated, white-furred, with a sprig of holly in his cap,” of girls ringing Salvation Army bells, gaily-colored Christmas magazines on the newsstand, wreaths for sale at the flower stall, and a peddler on the corner selling glossy holly from a crate.

Despite being nearly one hundred years old, this is a familiar, homelike scene to those who have spent Christmases in urban America. There are certainly interesting differences between how Americans celebrated Christmas in the 1920s and today, yet in my research what I have discovered is that some of the elements of Christmas that in 2018 we consider “classic” in fact originated or crystallized in the 20s.

Christmas was increasingly family-centered in the 20s, Susan Waggoner writes, as opposed to the whirl of social and public activities that characterized Christmastime in earlier eras. Nativity plays performed by little children became the norm. For example, the cast of characters for Maude Summer Smith’s The Busy Christmas Fairies: A Short Operetta for Kindergarten or First Grade Children, published in 1922, includes:

The Wicked Night Wind Fairy—a small boy.

Santa Claus—a large boy or girl.

Christmas Fairies—not more than twelve, both boys and girls.

Earth Children—The rest of the Kindergarten.

Sounds absurdly cute, doesn’t it? Radios, available for use in the privacy of the home, also boosted the more domestic nature of Christmas in the decade. And as radio ownership increased, so did the demand for seasonal songs. Chart-topping Christmas songs of the 20s include “Adeste Fideles” performed by the Associated Glee Clubs of America in 1925, and “Auld Lang Syne” performed by the Peerless Quartet in 1921. “Parade of the Wooden Soldiers”—a sprightly march written in 1897 and probably familiar to some of you—was a repeat hit with chart-topping versions performed by the Vincent Lopez Orchestra in 1922, Carl Fenton’s Orchestra in 1922, and Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra in 1923. I admit that “Parade of the Wooden Soldiers” is catchy, but there must be some mysterious ingredient that made it so very beloved to people in the 20s. You can listen to some of these tracks on YouTube and judge for yourself.

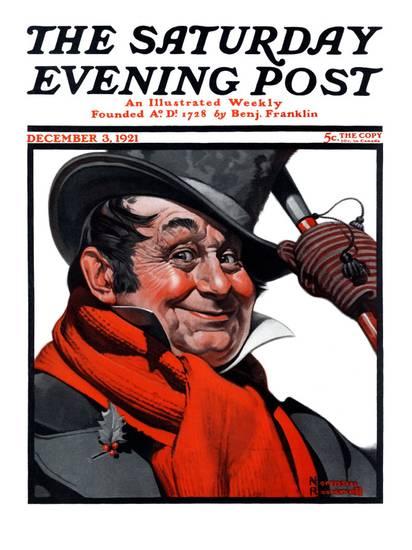

Judith Waggoner writes that “After the shock of World War I, people craved the comfort of more innocent times. They found it in the world of Charles Dickens. There were four different film versions of A Christmas Carol to choose from, and magazine covers of the era often depicted scenes with the flavor of merry old England.” The “old English” sort of Christmas, by the way, never really existed in America; U.S. Puritan heritage has been decidedly opposed to Christmas merrymaking. Thus, the pseudo-Dickensian yuletide of the 1920s amounted to pure nostalgic fantasy. This nostalgia translated into decorations with carriage lantern and antique candle holder motifs, and Victorian-style paper silhouettes, while English holly, rather than today’s pine boughs, were the favored holiday greenery. (In fact, in my home region of Western Washington State, holly planted in the 1920s as a holiday cash crop is now considered an out-of-control invasive species.) In keeping with that pseudo-Dickensian theme, Norman Rockwell’s cover for The Saturday Evening Post’s December 3, 1921 issue depicts a ruddy-cheeked coachman in a Victorian top hat and collar, with holly on his lapel. Similarly, Rockwell’s December 8, 1928 cover shows a man and woman in mid-nineteenth-century attire dancing beneath the mistletoe. They, too, are ruddy-cheeked. Must be something in the punch.

Judith Waggoner writes that “After the shock of World War I, people craved the comfort of more innocent times. They found it in the world of Charles Dickens. There were four different film versions of A Christmas Carol to choose from, and magazine covers of the era often depicted scenes with the flavor of merry old England.” The “old English” sort of Christmas, by the way, never really existed in America; U.S. Puritan heritage has been decidedly opposed to Christmas merrymaking. Thus, the pseudo-Dickensian yuletide of the 1920s amounted to pure nostalgic fantasy. This nostalgia translated into decorations with carriage lantern and antique candle holder motifs, and Victorian-style paper silhouettes, while English holly, rather than today’s pine boughs, were the favored holiday greenery. (In fact, in my home region of Western Washington State, holly planted in the 1920s as a holiday cash crop is now considered an out-of-control invasive species.) In keeping with that pseudo-Dickensian theme, Norman Rockwell’s cover for The Saturday Evening Post’s December 3, 1921 issue depicts a ruddy-cheeked coachman in a Victorian top hat and collar, with holly on his lapel. Similarly, Rockwell’s December 8, 1928 cover shows a man and woman in mid-nineteenth-century attire dancing beneath the mistletoe. They, too, are ruddy-cheeked. Must be something in the punch.

However, at the same time that the Prohibition era gazed back, misty-eyed, to a more wholesome Christmas Past, it also embraced new technology and design during the Christmas season. For example, General Electric introduced its new cone-shaped Christmas tree light bulbs in 1922, Art Deco motifs emerged on wrapping paper, newfangled toys like Pogo sticks and Lincoln Logs showed up beneath Christmas trees, and innovations in plastic allowed Kewpie dolls to come into existence (Oh happy day). What is more, once the financial prosperity of the 20s really got rolling, it helped to solidify the frantic shopping that Americans to this day both celebrate and lament.

The New Butterick Cook-Book, published in 1924, offers these two menu options for Christmas dinner:

Christmas Dinner: No.1: Oyster Cocktails in Green Pepper Shells, Celery, Ripe Olives, Roast Goose with Potato Stuffing, Apple Sauce, String Beans, Potato Puff, Lettuce Salad with Riced Cheese and Bar-le-Duc French Dressing, Toasted Wafers, English Plum Pudding, Bonbons, Coffee. No.2: Cream of Celery Soup, Bread Sticks, Salted Peanuts, Stuffed Olives, Roast Beef, Yorkshire Pudding, Potato Soufflé, Spinach in Eggs, White Grape Salad with Guava Jelly, French Dressing, Toasted Crackers, Plum Pudding, Hard Sauce, Bonbons, Coffee.

Christmas Dinner: No.1: Oyster Cocktails in Green Pepper Shells, Celery, Ripe Olives, Roast Goose with Potato Stuffing, Apple Sauce, String Beans, Potato Puff, Lettuce Salad with Riced Cheese and Bar-le-Duc French Dressing, Toasted Wafers, English Plum Pudding, Bonbons, Coffee. No.2: Cream of Celery Soup, Bread Sticks, Salted Peanuts, Stuffed Olives, Roast Beef, Yorkshire Pudding, Potato Soufflé, Spinach in Eggs, White Grape Salad with Guava Jelly, French Dressing, Toasted Crackers, Plum Pudding, Hard Sauce, Bonbons, Coffee.

In keeping with that pseudo-Dickensian nostalgia, notice that the menus include the Tiny Tim Cratchit-worthy entrees of roast goose and roast beef with Yorkshire pudding, and both menus include the oh-so-English plum pudding. On the other hand, the 20s were positioned near the beginnings of Big Food: “Wonder Bread, Girl Scout cookies, Kool-Aid, and Popsicles all made their first appearance during the decade,” P. J. Hamel writes, “Jell-O, introduced in 1897, became a pantry staple, and by the 1920s was termed ‘America’s most favorite dessert’.” In 1911, Proctor & Gamble had placed Crisco on market shelves, and although the product at first was met with resistance from cooks reluctant to replace butter and lard, by the 20s it had become a common household staple.

Last but not least, there was the outlawed booze. A coveted Christmas gift for the fellows was top-shelf tipply smuggled down from Canada. A single bottle of illicit Seagram’s cost the equivalent of $142 in today’s currency once it reached New York City. Judith Flanders writes of an eyebrow-raising connection between Santa Claus and black-market alcohol. During the 20s, the image of a florid, jelly-bellied Santa Claus, although around since the mid-Nineteenth Century, was cemented as “the” image and became mass-produced, particularly in print ad campaigns.

“One of the earliest extended campaigns to make use of Santa was that of the Wisconsin-based White Rock mineral-water company, which ran advertisements from 1915 to 1925 showing Santa at home, at work, making deliveries. Although White Rock was merely carbonated water, it was used as a mixer for alcoholic drinks. Gradually, therefore, as the advertisements ran during Prohibition, White Rock became a synonym for alcohol.”

Naughty, naughty, Santa.

Here are a few more fun facts about 1920s American Christmases:

- Americans had a preference for girthy, round Christmas trees, the bulgier the better.

- Lametta, a type of tinsel manufactured in Germany, was made of lead alloy foil with tin bonded on top. Keep that away from the kids. Other tinsel was ultra-flammable paper-covered aluminum.

- Paper decorations were popular, including the ubiquitous red tissue honeycomb bell.

- Snow Babies figurines (you’ve seen those, right?) date back to the 20s.

- Since Scotch tape had not yet been invented, gift-wrappers had to make do with decorative, lick ‘em adhesive seals.

Maia Chance is the author of several mystery novels, including The Discreet Retrieval Agency mysteries, the Agnes and Effie Mysteries, and the Fairy Tale Fatal series. Her latest mystery, Naughty on Ice (Discreet Retrieval Agency #4), set during Christmastime in 1923 Vermont, is available wherever books are sold. Find Maia at facebook.com/MaiaChance and at maiachance.com.

Works Cited:

Drahl, Carmen. “What Is Tinsel Made Of?” C&EN: Chemical Engineering News, 15 December 2014, cen.acs.org/articles/92/i50/Tinsel-MadeChanged-Over-Years.html.

Editors of Peter Pauper Press. A Century of Christmas Memories: 1900-1999. White Plains NY: Peter Pauper Press Inc., 2009.

Flanders, Judith. Christmas: A Biography. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2017.

Forbes, Bruce David. Christmas: A Candid History. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007.

Hamel, P. J. “American Baking Down the Decades, 1920-1929: Cake Meets Technology.” Flourish, 9 March 2015, blog.kingarthurflour.com/2015/03/09/american-baking-decades-1920-1929

Macdonald, Fiona. Christmas: A Very Peculiar History. Brighton, UK: The Salariya Book Company Ltd., 2012.

Olver, Lynne. “Historic American Christmas Dinner Menus.” Food Timeline, 3 January 2015, foodtimeline.org/christmasmenu.html.

Smith, Maude Summer. The Busy Christmas Fairies: A Short Operetta for Kindergarten or First Grade Children. Franklin, Ohio: Eldridge Entertainment House, 1922.

Waggoner, Susan. Christmas Memories: Gifts, Activities, Fads, and Fancies, 1920s-1960s. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 2009.

Waggoner, Susan. Have Yourself a Very Vintage Christmas. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 2011.

Warner, Frances Lester. Merry Christmas from Boston. Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1921.

The post Christmas in 1920s America appeared first on The History Reader.

Powered by WPeMatico