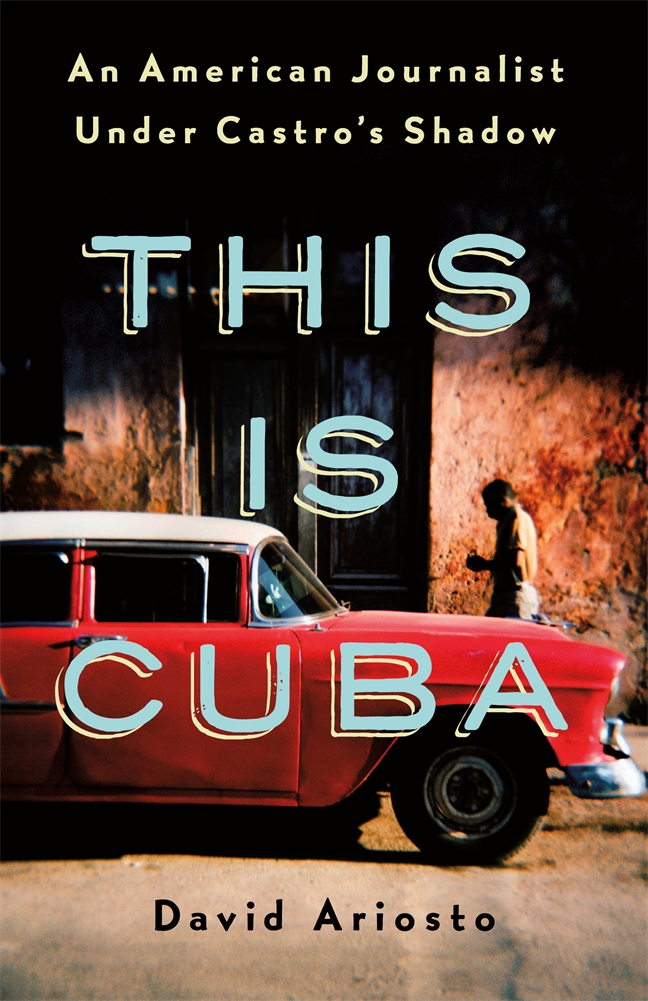

by David Ariosto

For David Ariosto, the island of Cuba is an intriguing new world, unmoored from the one he left behind. From neighboring military coups, suspected honey traps, salty spooks, and desperate migrants to dissidents, doctors, and Havana’s empty shelves, Ariosto uncovers the island’s subtle absurdities, its Cold War mystique, and the hopes of a people in the throes of transition. Beyond the classic cars, salsa, and cigars lies a country in which black markets are ubiquitous, free speech is restricted, privacy is curtailed, sanctions wreak havoc, and an almost Kafka-esque goo of Soviet-style bureaucracy still slows the gears of an economy desperate to move forward.

But life in Cuba is indeed changing, as satellite dishes and internet hotspots dot the landscape and more Americans want in. Still, it’s not so simple. The old sentries on both sides of the Florida Straits remain at their posts, fists clenched and guarding against the specter of a Cold War that never quite ended, despite the death of Fidel and the hand-over of the presidency to a man whose last name isn’t Castro.

And now, a crisis is brewing.

In This Is Cuba, Ariosto looks at Cuba from the inside-out over the course of nine years, endeavoring to expose clues for what’s in store for the island as it undergoes its biggest change in more than half a century. Keep reading for an excerpt.

* * * * *

I sipped an amber rum. Habana Club. Seven years. No ice. He palmed a Bucanero beer, half wrapped in a flimsy white paper napkin. Curls of Cohiba smoke wafted between us, giving the room a translucent look and an acrid taste. Castro was having a drink. And so was I. It was a Friday evening in late November 2010, and we were ensconced on opposite ends of a small subterranean saloon on the western outskirts of Havana. It was my last night in Cuba.

I sipped an amber rum. Habana Club. Seven years. No ice. He palmed a Bucanero beer, half wrapped in a flimsy white paper napkin. Curls of Cohiba smoke wafted between us, giving the room a translucent look and an acrid taste. Castro was having a drink. And so was I. It was a Friday evening in late November 2010, and we were ensconced on opposite ends of a small subterranean saloon on the western outskirts of Havana. It was my last night in Cuba.

Jammed in the crevices of my back pocket was a one-way ticket to Miami, scheduled for the following morning, the first leg of a connecting flight to New York City. For the past year and a half, Havana had been home during my stint as a photojournalist for CNN on an island still forbidden to most Americans. But now I was ready to leave—forever, I thought. My father, who lived in the pinelands of southern New Jersey, had been sick following acute kidney failure, which punctuated my own recognition that life in Castro’s Cuba didn’t much suit me anymore. So I had found a job as an editor in New York, exchanged my house on the Caribbean for a studio apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and traded the guayabera for a suit and tie; Cuban heat for a wintry chill. Crazy, it seemed, but Gotham was beckoning.

Then again, this was my last night in Havana. Better make the most of it.

“Do you know who that is?” whispered Antonina, a server in La Fontana, the private, family-run restaurant, or paladar, to which that smoky bar was attached.

“No,” I replied. “Who?”

There was usually a breezy familiarity in the way she spoke, imbued with a Caribbean warmth and that marbles-in-your-mouth accent for which much of Cuba is known. The banter was usually light. The topics rarely serious.

But tonight was different. Antonina seemed different, the burden of her words a bit heavier than usual. Inside that paladar, a steady crop of regulars had shuffled in. Rum and cigars, coupled with a live singer or guitarist, usually helped to lighten the mood. But tonight, a palpable tension gripped the air. And the staff seemed to feel it. It was a sensation to which many had grown accustomed.

Situated on a leafy street a few blocks from Havana’s rocky northern coast, La Fontana had opened in 1995 when authorities still investigated private restaurants for their numbers of tables and chairs (more than twelve could provoke a raid). Its clandestine feel—there was no sign outside and a surrounding stone wall all but hid the restaurant from view—was part of a broader bid for its very survival. And it looked it. The Castro government had almost never regarded privatization kindly, granting business licenses only when economic forces compelled a drip of liberalizing reform. But in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse, a financial crisis had ensued. For decades, Cuba had relied on subsidies from Moscow. In their absence, it teetered on the brink of collapse. Absent his old Kremlin ally, Fidel looked inward for answers and reluctantly allowed a few private restaurants to surface in a fraught attempt to gin up local commerce. La Fontana’s two owners, Horacio Reyes-Lovio and Ernesto Blanco, were among the beneficiaries of the new tone and would soon become successful restaurateurs—a dangerous prospect on an island dominated by Communist hard-liners who had spent their careers fending off “yanqui capitalists.” New concentrations of wealth were forming that could undermine the Revolution. So the two businessmen kept their profiles low and were quietly, if not begrudgingly, allowed to thrive. Perhaps even government officials were loath to shut down one of the few haunts where they could still score a decent meal.

By the time I arrived in Havana, in June 2009, that old paladar had been transformed into a favorite hangout for politicians, their staffs, and foreign businesspeople alike. It was a place to eat, drink, and—in my case—write, mostly from the vantage point of a still somewhat naïve American journalist. A fixture there, I’d often scratch out pages alone atop one of the few polished wooden tables in back, filling a leather-bound notebook with run-on sentences, notes, and smears of blue ink. They were random observations, mostly. A sort of blind attempt to piece together this confounding puzzle of a nation that I now called home. His approach. Her look. Their meeting. A dribble of insight that seeped through the censors of state-run newspapers.

Typical street in old La Havana, Cuba. Photo Credit: Christophe Meneboeuf

(Creative Common CC-BY-SA License)

After a few months and what amounted to a few notebooks full of mostly useless pages, I had gotten to know the restaurant’s staff. One was Antonina, whose frankness and sharp tongue seemed matched only by her curiosity. It was the former that made us friends and the latter that would drive her to leave the island as a refugee. But before she did, her occasional rum-topped whispers would help fill in my own knowledge gaps, chasms really, when it came to Cuba. Men like Ricardo Alarcon, then president of Cuba’s National Assembly, were among La Fontana’s well-heeled patrons who often chatted and sipped mojitos with a hardy crop of familiar faces. I’d try without much luck to listen in, attempting to discern with whom he was meeting and what they were discussing. Business could be conducted this way, and the eavesdropping went both ways.

But tonight, my last night, I wondered why Antonina was so serious and to whom she had so subtly pointed. Passing behind me with a tray of empty glasses, she leaned into my ear.

“That’s Alejandro,” she whispered, brushing back the unkempt strands of raven-colored hair that dropped in front of her face.

By “Alejandro,” Antonina had meant Alejandro Castro Espín, a colonel within Cuba’s powerful Interior Ministry and a member of the Castro family, whose inherited importance seemed to be out- pacing much of the rest of the Castro clan’s. It was President Raul Castro’s only son who now sat across from me at the bar. How could I not have realized that before? Of course, in November 2010, the extent of Alejandro’s importance was not yet clear. He had yet to broker secret deals in Ottawa and Toronto with top Obama advisers Ben Rhodes and Ricardo Zúñiga, nor had he presided over a spy-for-spy negotiation that would lay the groundwork for détente. What was clear was that Alejandro was already a player and a de facto top adviser to his father. More importantly, he was rumored to be gaining in power atop the senior echelons of the very agency tasked with Cuba’s surveillance and counterintelligence; his ministry spied on journalists and dissidents alike. And by apparent coincidence, in my final hours in Cuba he sat across from me, slouched over a beer.

“Coño!” exclaimed Rafa—employing his favorite Cuban expletive— when I later told him of the encounter. Rafael, or “Rafa” for short, was a driver at CNN, and his eyes bulged as he pronounced just the ño in that typical Cuban habit of dropping whole syllables. Though he quickly recuperated, casually popped his shoulders, and gave me this simple—though at the time nonsensical—explanation:

“This is Cuba.”

I had come to loathe that line, which was by now all too familiar—a favorite amongst those who seemed intent on explaining the unexplainable. In literal terms it meant little. Yet it also perfectly encapsulated everything about Cuba that was maddening, unknowable, and completely out of your hands. Even Cubans without a basis for comparison seem to know, perhaps by way of the trickle of information that seeps in from outside, that their island is somehow different.

“This is Cuba.”

That Alejandro Castro Espín, one of the very men responsible for the sort of paranoid patina that coats the island, just so happened to be seated at my go-to bar on my last night in Havana . . . yeah, “This is Cuba” seemed apt.

DAVID ARIOSTO is Executive Producer of GZERO media at the Eurasia Group. Previously, he has worked for Brut, CNN, NPR, Al Jazeera America, Reuters and National Geographic. Between 2009 and 2010, Ariosto was based in Havana, Cuba, working as a photojournalist for CNN. He continues to make reporting trips to the island several times each year. Ariosto also holds a Master’s of Public Policy degree from George Mason University and a Bachelor’s of History degree from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. He lives in New York.

The post An American Journalist Under Castro’s Shadow appeared first on The History Reader.

Powered by WPeMatico