For people in the Middle Ages keeping track of time was all important. One chalennge was to know when markets were held. Another when to sow, harvest and feast. Early on, the Church set up itself as timekeeper par excellence. But how did clerics keep the time? New book introduces the student to the intraicacies of medieval timekeeping.

For people in the Middle Ages keeping track of time was all important. One chalennge was to know when markets were held. Another when to sow, harvest and feast. Early on, the Church set up itself as timekeeper par excellence. But how did clerics keep the time? New book introduces the student to the intraicacies of medieval timekeeping.

The Medieval Calendar

Locating Time in the Middle Ages

By Roger S. Wieck

The Morgan Library and Museum, New York. In association with Scala Arts Publisher, Inc. 2017

Review

More calendars survive from the Middle Ages than any other type of document, writes Colin A. Baily in his foreword to a new book, published in connection with an exhibition at The Morgan Library and Museum in New York, spring 2018. This remark from the director of the museum is probably not entirely correct. Gospels, theological treatises and religious handbooks in the form of missals, breviaries and psalters – or for lay people, books of hours – would constitute the bulk. Calendars seldom constituted “books” on their own. As a matter of necessity, however, most of these types of books would also hold Easter tables and later calendars. The point, though, that these manuscripts often included or were organised as calendars, thus indicate that the observation is not far from the target.

The fact is, that time mattered immensely to medieval people. The question is only how and in what way medieval timekeeping differed from ours? And how it set its mark on medieval imagery?

These questions are central to this new book written by Roger S. Wieck. Apart from being the curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts at Morgan, he also teaches an introductory course at the “Rare Book School” – http://www.medievalhistories.com/rare-book-school/ – in Virginia. The present book holds the sum of this teaching and is as such a generous gift to all those students who have not been able to partake in these courses, but who might nevertheless benefit mightily from sharing the experiences of a man, who has handled manuscripts most of his life. More precisely, the book aims to enlighten about how we should go about localising calendars and what we as students might learn apart from delving into the eye-candy of the miniatures, with which medieval calendars were so often embellished.

The Book is divided into three chapters of which the first is a general introduction to the genre, the second a case-study of the Calendar for the Sainte-Chapelle in France and the third delves into the more tricky question of how to identify and localise a Calendar.

In the general introduction, we learn how calendars’ primary purpose was to identify and rank religious feasts, be they of the global, national or local variety. Such feasts were the backbone of the rhythm of any year. To men, they might indicate when to start or not on a journey or a commercial enterprise, something which was not propitious to embark upon on one or the so-called bad-luck days, of which each month held several. Or it might be pertinent for a wife to know when not to engage in connubial activities, which were prohibited for long stretches of time, on fast-days etc. What is even more interesting is to get of sense of how to compute when the movable feast of Easter would fall. Something, which might be highly valuable in case you were invited to spend the holidays at the castle of your lord, and you needed to prepare to set out in time. Here a medieval calendar was a necessary tool. Fitted with Golden Numbers and Sunday Letters any calendar would help you on the way if only you (or your resident friar or priest) knew how to compute it. But don’t despair, Roger Wieck tells you how to proceed, if you do not take the lazy way out and consult a modern “eternal calendar” (as I always do). This chapter, however, also introduces the reader to an overview of the art and miniatures, which so often accompanied the calendars. Local conditions might vary, but it nevertheless seems there early on was a distinct symbolic activity connected with each month (warmth for January etc.). Harvesting wine, though, which the standard indicates should take place in October, hardly characterised the yearly round in medieval Scandinavia. Here sowing of winter seed (rye) would be more appropriate. The introduction presents us with multiple examples of these differences as well as how they were accompanied by the proper zodiacal signs.

Moving on to the Calendar for Sainte Chapelle (MS M.1042) in a breviary made in the late 13th century in Paris, we get a slow and careful walk through the specifics, as presented in the introduction. Here any budding codicologist may explore the way in which a proper description and analysis of a medieval manuscript may be carried through. This calendar is chosen, as it is easily identified through its near twin, the royal breviary of Philippe Le Bell (BNF Lat1023) – http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90665543/f3.image .

Complete with a table of abbreviations and page-for-page reproduction, transliteration and commentary it becomes a real joy to explore this particular manuscript guided by a master-hand. We know that the celebration of the morning mass was an obligatory part of any royal or seigniorial household. With the present edition, we get the chance in the grey morning light of dawn to follow in the footsteps of Jeanne de Navarre up the stairs and into the upper chapel of the Sainte-Chapelle to share the particular readings for each feast day.

Finally, we get a manual on how to localise a calendar. In what language is it written? Which saints does it celebrate? Which websites should you consult to identify the particular saints and their feast-days? As an additional service, we are carried through additional exercises: the Hours of Charlotte of Savoy, the Psalter of Charles VIII etc

This is indeed a delightful book. As a non-codicologist, I confess, I learned a lot about how to delve into local calendars and get them to bleed information on a less superficial level.

Should one add a caveat, though, it would be that the manuscripts presented are nearly all French or Flemish. We are obviously digging the yard of the sublime collections at Morgan. Not every calendar, though, can as easily be identified. Some calendars might have changed hands and hence been subject to additions and corrections mudding the waters. For instance, The Christina Psalter (GKS 1606 4°) a thirteenth-century Parisian Manuscript in the Royal collections in Copenhagen was traditionally associated with Christina of Norway, a Norwegian princess (1234 -1262). The manuscript, however, was later amended as it moved from one owner to the next adding to and erasing saintly feasts as seemed appropriate. Not only might all calendars not be localised, as Wieck writes. They might also carry traces of different localisations, thus obscuring their sites of production and their primary owner.

Calendars are wonderful pieces of art. As such, it is important to know exactly where, when and by whom they were created. Just as important though is to know for whom, as well as the where and how they were used.

Beautifully illustrated with copious illustrations from the collections of Pierpont Morgan, the book is highly recommended as an introduction to the field of medieval calendars.

Karen Schousboe

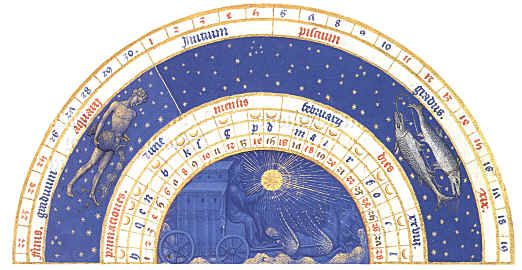

FEATURED PHOTO:

Liturgical calendar for Ravenna, Italy, Milan (?), 1386, illustrated by a follower of Giovannino de’ Grassi, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.355, fol. 8v (detail), purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

The post The Medieval Calendar in Books of Hours appeared first on Medieval Histories.

Powered by WPeMatico