by Tasha Alexander

…let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings;

How some have been deposed; some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed;

Some poison’d by their wives: some sleeping kill’d;

All murder’d…

—William Shakespeare, Richard II

When we think about the kings—and queens—of England, we generally consider the triumphs and failures of their reigns, the elegant palaces in which they lived, and the scandals of their courts. For monarchy to work, both the ruler and his or her subjects have to believe there is something that sets the royals apart from everyone else. Take the concept of divine right, for example, in which God grants the king his power, making the monarch subject to no human authority. The definition of aristocracy in the Oxford English Dictionary reminds us that nobles are supposed to be the best citizens, above everyone else. And the king sits at the top of the aristocracy. So it’s easy to see why many people are programmed to think these individuals are somehow better than the rest of us.

In fact, they’re just as human—and flawed—as everyone else, something that is driven home by many of their deaths.

Queen Victoria’s death at Osborne House in 1901 conforms to the stereotype of a noble death: she succumbed to illness after a long and celebrated reign, surrounded by family, mourned by her empire. But not all of her compatriots went so gently into that good night.

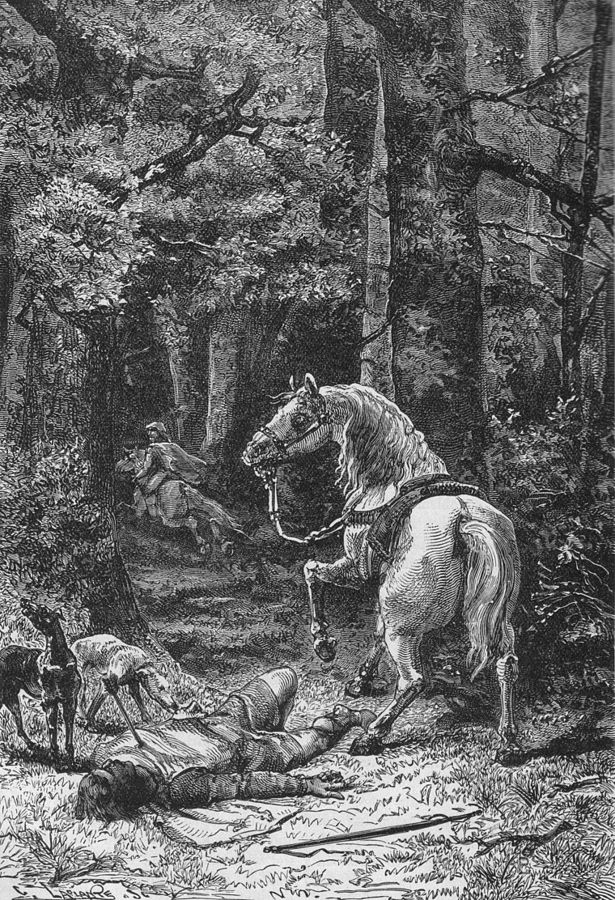

Death of William Rufus, lithograph by Alphonse de Neuville, 1895

In 1135, William II overindulged during a raucous evening, after which he slept poorly, tormented by bad dreams. The next morning, probably suffering from a profoundly human hangover and still troubled by the memories of his nightmares, he was less than enthusiastic about his plan to hunt that day. But hunt he did. Unfortunately for him, the only other member of his party, aiming his crossbow at a stag, hit the king instead. The Chronica Maiora tells us: The shaft flew, and glancing off a tree pierced the King full in the heart, so that he instantly dropped dead.

A dreadful accident. Or was it?

First of all, two parties had gone out hunting. The king’s consisted only of himself and Walter Tyrrel, a skilled archer. After William fell, Tyrrel fled, leaving the royal body in the New Forest. Tyrrel joined a crusade—guilty conscience?—and locals found William’s remains. Conveniently, William’s brother Henry, keen to see himself one the throne, was with the other, larger party, and he lost no time in getting to Winchester, where, the next day, he was proclaimed king. The timing was more than a little convenient, as the other potential claimant, his older brother Robert, was away from England on crusade. Strong, popular, and, as the eldest son in the family, Robert would have proven a formidable opponent for the crown. Had William died when both his brothers were in England, Henry might never have been king.

Poor William, so unloved, was quietly buried in Winchester, his courtiers not bothering to attend the funeral.

It all worked out well for Henry. At least that’s how it seemed.

Henry I ruled for 35 years and had a reputation for cruelty. Perhaps it was a bit of divine justice that after gorging on lampreys—against his doctors’ advice—he fell suddenly and fatally ill. Regardless, his death could never be held up as dignified, let alone noble and courageous. Like the rest of us, he was human, and let his appetite get the better of him.

TASHA ALEXANDER, the daughter of two philosophy professors, studied English Literature and Medieval History at the University of Notre Dame. She and her husband, novelist Andrew Grant, live on a ranch in southeastern Wyoming. She is the author of the long-running Lady Emily Series as well as the novel Elizabeth: The Golden Age.

The post The Death of Kings appeared first on The History Reader.

Powered by WPeMatico