St. Martin was a Roman soldier, who turned into a Christian ascetic. Later he was adopted as a national saint for France, as well as a soldier of Christ. His final disguise, though, was as a popular saint

While St. Martin was busy competing with other national saints, he was also recruited as a prominent player in the Benedictine reform movement. Launched by Abbot Odo of Cluny in the 10th century, it set its mark on the coming millennium. In 903 the great Basilica at Tours had burned to the ground. Odo, who witnessed this event in his youth, relived the horror in the 940s, and used it as inspiration for a famous sermon, “de combustione”, in which Odo presented the fire as a divine reprobation prompted by the sinful life, the wasteful sloth, and especially their luxurious clothes and impure lifestyle, which characterised the monastic and ecclesial communities at Tours. Through this sermon, Odo peddled his Cluniac version of monastic reform to his listeners and readers claiming St Martin as its spearhead. In tune with this, Odo returned to Tours when he was dying.

Odo’s endeavour was without a doubt widely successful. Just as important, though, was the German Reform Movement, which originated in 933 at the Abbey of Gorze, near Trier. This Abbey was dedicated to yet another high-ranking Roman officer, Gorgonius of Rome, an early Christian martyr. The location of the Abbey of Gorze, near another famous Abbey at Tholey, dedicated to St. Maurice, and the less prominent Abbey of St. Martin at Trier, indicates that the frontier between East and West was peopled with competing soldier-saints, all ready to be enrolled in the project of civilising both rulers, religious institutions, and their dependant warriors, as well as enhancing the status and power of their respective realms. To this might be added St. George, who entered the Pantheon from the south (Greece and Italy).

St. Martin and his Cloak

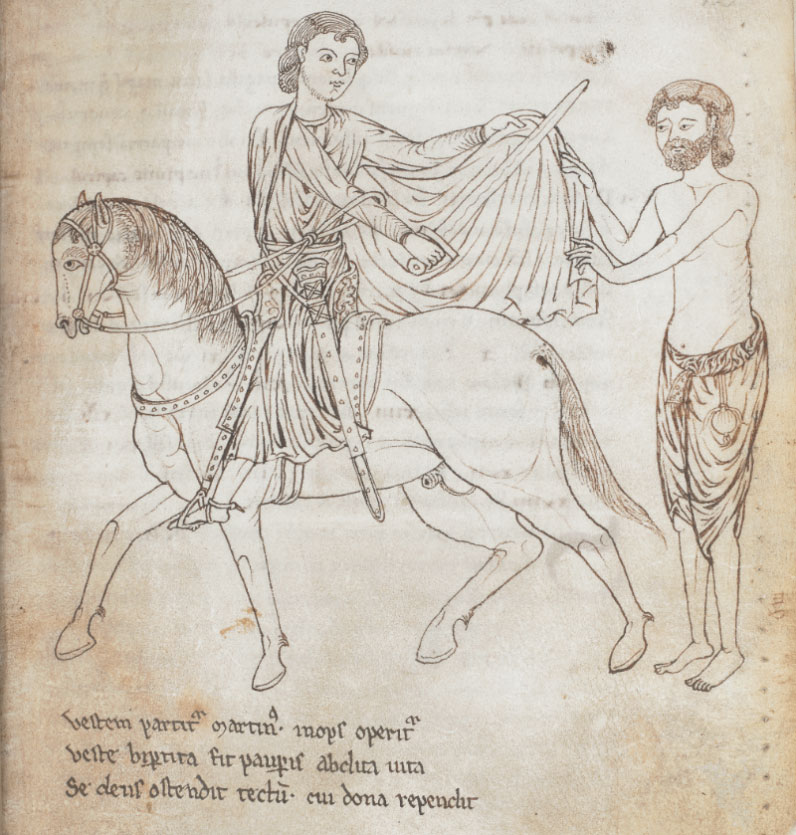

St. Martin, though, succeeded where others failed in also becoming a particularly popular saint. It is likely this fame rested upon what seems for us to be the primary symbol of his life, the miracle of how St Martin shared his cloak with a beggar and discovered in his dream, it was Jesus, he had encountered.

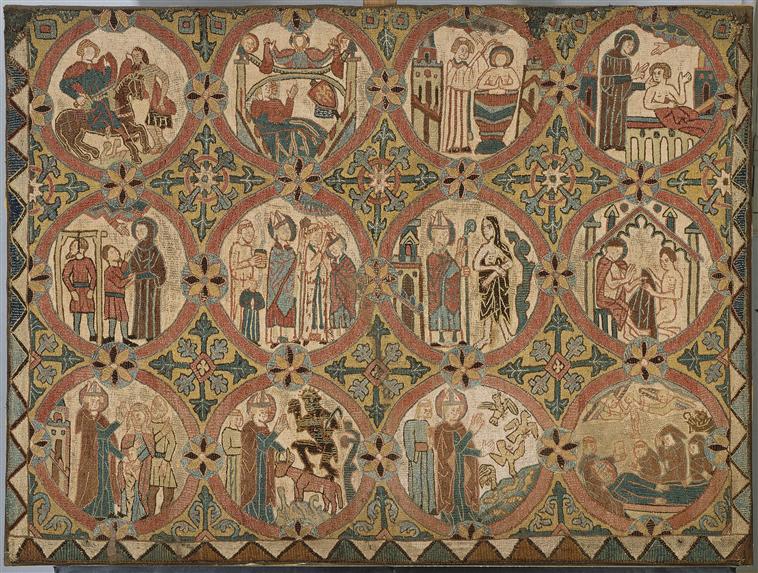

Curiously enough, though, this vignette – called the Charity of St. Martin – had not been part of the visual repertoire until the 10th century. The scene is first found in the so-called Fuldaer Sakramentar from c. 997 – 1011 (Udine, Biblioteca Capitolare, Cod. 76 V – (Udine, Biblioteca Capitolare, Cod. 76 V).

Although St. Martin was widely venerated, traces of earlier paintings narrating events from his vita are sorely missing. It has been suggested that the painting in the manuscript from Fulda is a copy of a painting found on the walls of the Basilica in Tours, which burned down in 903, but this is just speculation. Until then, Martin would solely be rendered in the form of portraits or as bishop. A fine example is an ivory cover to a manuscript from c. 800 – 900, where the beggar is seen at the top, with a teaching bishop below (Berlin, destroyed in 1945). Notably, though, the sharing of the mantel is not featured. Rather, Martin is presented as a bishop engaged in teaching.

Was the story of the beggar suppressed until the 11th and 12th century because it did not fit with the propriety of a saintly bishop? Ælfric was an English Abbot (955 – 1010) and a prolific writer of all sorts of texts – hagiographies, homilies, biblical commentaries, and involved in promoting the English version of the Benedictine reform. In connection with his writings, he became extensively fascinated by St Martin of Tours, who ended up figuring in both his collection of Homilies and his Lives of Saints. In these writings he reused nearly everything, he might lay his hands on from Sulpicius’ early vita to the writings of Gregory of Tours. The interesting question is how he chose to present the holy man to his listeners. In what way did Ælfrics St Martin differ from that of the early biographers? First of all, it appears as if Ælfric chose to ignore Martin’s military career, obviously troubling for a man of the cloth bent on promoting a more civilised world than the very violent one, in which he was living. But also his asceticism and humility seem to have troubled Ælfric, finding it might subtract from his moral status as a bishop, proper. Nowhere is this as evident as in the story of St Martin sharing his tunic. Sulpicius writes that his fellow soldiers laughed at Martin because he was he was unsightly and only half clad. In Ælfric’s writings, however, the holy man is not the object of scorn, instead, the mutilated garment is the cause of their merriment. One might say that Ælfric’s Martin is a sanitised and dignified version. Decorum obviously had to be preserved in late 10th century Anglo-Saxon England. As such, the story of St. Martin and the pauper had to be cleaned up. Dignity, as well as charity, were both important virtues to pursue and preserve at the turn of the first millennium.

In this connection, we might study the illuminations from the Fuldaer Sakramentar (featured above). Careful study of this manuscript, have shown that it was produced at Fulda, but for the use at the bishopric at Hamburg-Bremen. This is probably the reason why the central vignettes – apart from those derived from the scriptures – show missionary events: The baptism and martyrdom of St Bonifatius, the martyrdom of St Paul and St Peter, the martyrdom of St Lawrence, All Saints, the gift of the half mantel to the beggar by St. Martin, and finally the martyrdom of St. Andrew. The choice of miniatures shows the manuscript was made for an episcopal sea overseeing a new missionary field, Scandinavia. Looking at the painting showing St. Martin we notice that what he is sharing is indeed his mantle (and not his tunic as Sulpicius writes). We also see that he does not share his warm hoses, nor his shoes. There are limits to Martin’s generosity, it seems.

A Generous Church

Why would the story of St. Martin sharing his cloak with the beggar suddenly begin to figure more prominently in the 10th and 11th centuries? We might speculate that the church needed the story for two reasons. One was to reaffirm its central role at a time when royal protection for the older religious institutions was harder to come by. To some extent, the religious landscape was shifting with new saints cropping up and others on the wane. To bolster its institutions, the church sought on the one hand to reform itself; on the other hand to position itself as the protector of ordinary people (beggars). Balancing between these considerations was not easy, but a carefully manicured St. Martin might be perfect for the role.

On the other hand, the balance could easily be tipped. An anecdote told of Henry II and Thomas Beckett, while the latter was still chancellor of England, recounts how the two were riding merrily along on one hard winter’s night. Encountering a beggar in the street, the King began to taunt Beckett, prompting him to give up his coat of scarlet cloth lined with grey pelts. “You shall have the credit of this charity”, said the King to the Chancellor, who fought to keep his precious and very valuable cloak. To the merriment and boisterous joy of the king’s men riding behind. No wonder, most late medieval depictions of St. Martin and the Beggar show a luxuriously clad noble sharing a shanty cloak with pitiful freezing beggar!

The winter feast of St. Martin had early on been considered a day of reckoning. November was the end of the agricultural season, when peasants would take stock of their animals, deciding how many might overwinter, and which had to bleed (the month was called “blood-month). This was the time of abundance and the time for calling in rents to be paid. Greedy hands of sheriffs, reeves, and priests demanded their due as well as the choice cuts. At the same time, though, this was also the time for paying servants in kind, distributing their allowance in the form of new shoes and clothes.

Martinmas was definitely a day of reckoning. But it was also an important feast day celebrated with gluttony all over Europe. With abundant meat, wine, and beer, this was arguably the party of the year, perhaps even more so than Christmas and Carnival. Regarding money laid out by accountants, it is possible to see that the feast around Martinmas was ocasionally three times as expensive as that of Christmas and Epiphany. As such, the feast varied from place to place. In England, the main fare was beef, while geese came to be symbolic elements wherever they played a role in the local agrarian economy. In Southern Europe, Martinmas heralded the tasting of the new wine or must. No wonder “ Martinsman” in a Dutch and German context came to mean a jovial drunkard.

What was served? Beef, mutton, calves feet, and pies filled with “numbles”, that is the innards of deers, one source from Southern England from 1492 tells us. From Germany we hear of a present of a goose as early as in 1171. Later songs from the 14th century also document this traditional fare.

SOURCES:

Der Ursprung des Martinsfestes

Von Carl Vlemen

In: Zeitschrift für Vereiens für Volskunde. (1918), pp. 1 – 14

Geiteilte Mantel, Ein Hauch von Fasching und ein neuer Martinskult. Die Verehrund des Martin in der Frühen Neuzeit.

Von Martin Scheutz.

In: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte (2016) Vol 98, 1 pp. 95 – 134

Medieval English “Martinmesse”: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival

By Martin W. Walsh

In: Folklore (2000) Vol 11, No 2, pp. 231 -254

Af Mortensgaasens Historie

By R. Paulli and Marius Kristensen

In: Danske Studier (1932) pp. 166 – 170

The Old English Lives of St. Martin of Tours. Edition and Study

By Andre Mertens.

Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2017

Beggar’s Saint but no Beggar: Martin of Tours in Ælfric’s Lives of Saints.

By Karin E. Olsen

In: Neophilologus (2004) Vol 88, pp. 461 – 475

The post St. Martin – a Popular Saint appeared first on Medieval Histories.

Powered by WPeMatico