by Therese Anne Fowler

Alva Smith, her southern family destitute after the Civil War, married into one of America’s great Gilded Age dynasties: the newly wealthy but socially shunned Vanderbilts. Ignored by New York’s old-money circles and determined to win respect, she designed and built nine mansions, hosted grand balls, and arranged for her daughter to marry a duke. But Alva also defied convention for women of her time, asserting power within her marriage and becoming a leader in the women’s suffrage movement.

In A Well-Behaved Woman, with a nod to Jane Austen and Edith Wharton, Therese Anne Fowler paints a glittering world of enormous wealth contrasted against desperate poverty, of social ambition and social scorn, of friendship and betrayal, and an unforgettable story of a remarkable woman. Meet Alva Smith Vanderbilt Belmont, living proof that history is made by those who know the rules—and how to break them. Keep reading for an excerpt of A Well-Behaved Woman.

* * * * *

Alva decided to attend a meeting of the Society for the Betterment of Working Children, which Armide had joined not long before. The group met once each month at the home of its president. Miss Annalisa Beekman was a young Knickerbocker lady whose pale eyes and pale hair and pale skin made her vulnerable to disappearance if she stood too near draperies or wallpaper of similar tones. Alva joined her and some ten other young ladies in the Beekman drawing room, which looked out onto Tenth Street. Among those ten: Lydia Roosevelt, who upon seeing Alva assessed her figure and said, “Well, Mrs. Vanderbilt, who would have expected you here?”

Alva decided to attend a meeting of the Society for the Betterment of Working Children, which Armide had joined not long before. The group met once each month at the home of its president. Miss Annalisa Beekman was a young Knickerbocker lady whose pale eyes and pale hair and pale skin made her vulnerable to disappearance if she stood too near draperies or wallpaper of similar tones. Alva joined her and some ten other young ladies in the Beekman drawing room, which looked out onto Tenth Street. Among those ten: Lydia Roosevelt, who upon seeing Alva assessed her figure and said, “Well, Mrs. Vanderbilt, who would have expected you here?”

“This is a cause I support heartily. When my sister told me of the meeting, I didn’t wish to miss it.”

“How good of you. Do accept my condolences on the loss of your husband’s grandfather. Who knew he was so well off? It does, of course, enable you to be charitable—which is only to our benefit.”

“Rather, to the benefit of the children, you mean,” Alva said.

“Of course.”

“Of course. And you will recall that I have been engaged with charitable

efforts for years.”

Miss Beekman said, “Ladies, shall we come to order?”

“Do forgive me for being late,” called Armide as she hurried into the room. Behind her was a young lady Alva didn’t recognize. Armide ushered the lady in with her.

“Allow me to introduce Miss Mabel Crane. She’s newly arrived from San Francisco, California, and is eager to involve herself with good endeavors.”

The others gave polite smiles. Miss Beekman said, “California, you say? My, that’s far from here.”

“It was a really long journey,” said Miss Crane. She was a handsome girl, and well dressed. There was, however, no question that she was different. Her skin tone was more golden, her cheeks freckled, her hairstyle less formal than anyone else’s here. She was dressed as well as any of them, though, suggesting to Alva that she came from money but that the money was new.

“And will you be in our city for a while?” asked Miss Roosevelt.

“Oh, yes, I live here. My father got a house on Park Avenue near Fortieth—which I guess is a good part of town?”

“Many new residents are buying there,” Miss Roosevelt said. “Most of us live here in this area of town, where New York’s first families settled.”

Alva said, “Thank you, Miss Roosevelt. We all needed that history lesson.”

Armide and Miss Crane found seats, and Miss Beekman, appearing flustered, said, “I was about to bring us to order, so I’ll proceed.”

“Yes, do,” said Alva. “I know we are all eager to get to the business of this event.”

Miss Beekman laid out the agenda for the meeting, the first item being the secretary’s report on what they’d done at the previous month’s meeting, followed by another report of the activities they had accomplished on behalf of the society in the intervening weeks as well as in recent months. Alva listened with diminishing attentiveness; her back was aching, and the baby kept kicking her beneath her left ribs, and these reports were interminably boring.

“Forgive the interruption,” she said, shifting in her chair. “I want to be certain I understand the nature of this group. By what I’ve just heard, it appears that you raise money by hosting subscription teas and luncheons and dinner dances, and then the society writes a check to one children’s aid agency or another.”

“Yes,” said Miss Beekman. “That’s correct.”

“How many of the workplaces have you seen in person? That is to say, do you visit the factories? And what about the hospitals or the homes where the maimed children convalesce? This is not to malign any particular agency—but how do you know how the money is being spent?”

Miss Roosevelt said, “Have you forgotten our visit to that horrible tenement? I told these ladies all about it. None of us is interested in going to those places.”

“She said it was quite horrible,” Miss Beekman reiterated. “Seeing a dead girl—”

“Miss Roosevelt did not see the girl, she—”

“We prefer not to risk exposure,” Miss Roosevelt pressed on. “We send money.”

Alva smiled. “Well, this is of course commendable. But it risks ineffectiveness,” she said, addressing the group. “I believe we should see for ourselves what the real needs are, and then direct the money specifically and confirm its uses. Certainly you read the newspapers; too often the money ends up in the pockets of crooks. I’d like to propose an outing for midmorning tomorrow. We’ll visit the hospitals and inquire as to what materials these children most need.”

“That is a fine idea,” Miss Crane said. “We should have specifics, and give money directly.”

Miss Roosevelt sat forward in her chair. “Miss Beekman, it is apparent to me that there is a tremendous chasm between our approach and that of our prospective new members. Rather than see an eruption of conflict, which might delay our charitable efforts unduly, I move to invite those prospective new members to form their own society, separate from this one.”

Stadler Photographing Co., New York-Chicago. Image is in the public domain via Wikipedia.

Alva said, “You’re denying my membership?”

“Yours and Miss Crane’s, and any others who prefer your approach. All in favor?”

The secretary said, “You need someone to second your motion.”

“I second it,” said one of the other ladies.

“All in favor?” Lydia said, looking straight at Alva while she raised her hand.

Alva stood up, her own hand raised. “I could not approve more heartily.”

The next morning found Alva, Armide, Miss Crane, and Alva’s younger sisters at Charity Hospital on Blackwell’s Island, their first stop on a tour of welfare facilities throughout New York City. Avoiding the wards housing prisoners or anyone with contagions, they met children missing limbs and eyes, children who cried about being unable to work again, children who stared blankly at dingy walls and did not respond to conversation. They questioned nurses and doctors about how best to help and made lists of needed supplies.

In Alva’s parlor that evening, Jenny made tallies while Alva poured wine for everyone. She handed around the glasses. All of them were weary and overwhelmed by what they’d seen.

Julia said, “I didn’t wish to go this morning, but I suppose I’m glad I did. We almost ended up like those people. I mean, not injured, but so poor! If Alva hadn’t married William… ”

Miss Crane said, “Before my daddy found himself a little bit of gold and started building hotels, we lived in a two-room shack that didn’t even have water. I had a job digging rocks out of wherever the city was putting sidewalks in.”

Jenny drank her wine all in one go, then handed back the glass to Alva for refill. “I’ll go slower this time, don’t worry.”

Armide said, “One can see why Miss Roosevelt and the others prefer their approach.”

“Yes, it is easy to see,” Alva replied. “In the morning, I’ll make a list of the factories we should visit next week.”

THERESE ANNE FOWLER is the author of the New York Times bestselling novel Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald. Raised in the Midwest, she moved to North Carolina in 1995. She holds a BA in sociology/cultural anthropology and an MFA in creative writing from North Carolina State University.

The post Therese Anne Fowler’s A Well-Behaved Woman: A Novel of the Vanderbilts appeared first on The History Reader.

The

The

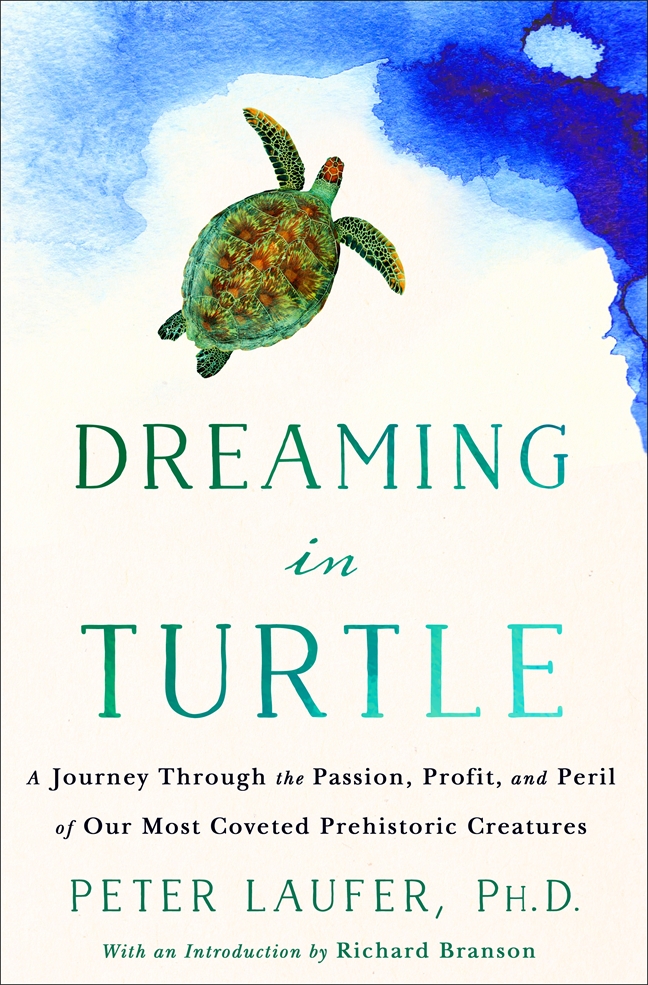

Meanwhile, Rao keeps looking for more, as do competing scientists from Europe and North America. Of course, they are not alone: with the high price tag as an indication of potential compensation for illicit trafficking of Yunnan box turtles, poachers are motivated to be out in force around the province seeking one of the rarest turtle species in the world – not for science but for profit.

Meanwhile, Rao keeps looking for more, as do competing scientists from Europe and North America. Of course, they are not alone: with the high price tag as an indication of potential compensation for illicit trafficking of Yunnan box turtles, poachers are motivated to be out in force around the province seeking one of the rarest turtle species in the world – not for science but for profit.

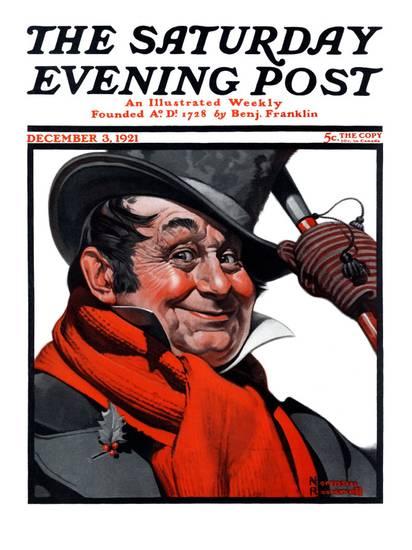

Judith Waggoner writes that “After the shock of World War I, people craved the comfort of more innocent times. They found it in the world of Charles Dickens. There were four different film versions of A Christmas Carol to choose from, and magazine covers of the era often depicted scenes with the flavor of merry old England.” The “old English” sort of Christmas, by the way, never really existed in America; U.S. Puritan heritage has been decidedly opposed to Christmas merrymaking. Thus, the pseudo-Dickensian yuletide of the 1920s amounted to pure nostalgic fantasy. This nostalgia translated into decorations with carriage lantern and antique candle holder motifs, and Victorian-style paper silhouettes, while English holly, rather than today’s pine boughs, were the favored holiday greenery. (In fact, in my home region of Western Washington State, holly planted in the 1920s as a holiday cash crop is now considered an out-of-control invasive species.) In keeping with that pseudo-Dickensian theme, Norman Rockwell’s cover for The Saturday Evening Post’s December 3, 1921 issue depicts a ruddy-cheeked coachman in a Victorian top hat and collar, with holly on his lapel. Similarly, Rockwell’s December 8, 1928 cover shows a man and woman in mid-nineteenth-century attire dancing beneath the mistletoe. They, too, are ruddy-cheeked. Must be something in the punch.

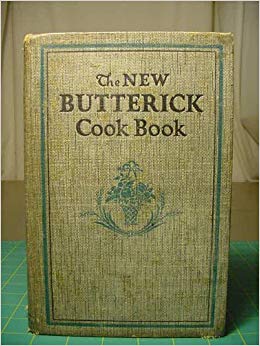

Judith Waggoner writes that “After the shock of World War I, people craved the comfort of more innocent times. They found it in the world of Charles Dickens. There were four different film versions of A Christmas Carol to choose from, and magazine covers of the era often depicted scenes with the flavor of merry old England.” The “old English” sort of Christmas, by the way, never really existed in America; U.S. Puritan heritage has been decidedly opposed to Christmas merrymaking. Thus, the pseudo-Dickensian yuletide of the 1920s amounted to pure nostalgic fantasy. This nostalgia translated into decorations with carriage lantern and antique candle holder motifs, and Victorian-style paper silhouettes, while English holly, rather than today’s pine boughs, were the favored holiday greenery. (In fact, in my home region of Western Washington State, holly planted in the 1920s as a holiday cash crop is now considered an out-of-control invasive species.) In keeping with that pseudo-Dickensian theme, Norman Rockwell’s cover for The Saturday Evening Post’s December 3, 1921 issue depicts a ruddy-cheeked coachman in a Victorian top hat and collar, with holly on his lapel. Similarly, Rockwell’s December 8, 1928 cover shows a man and woman in mid-nineteenth-century attire dancing beneath the mistletoe. They, too, are ruddy-cheeked. Must be something in the punch. Christmas Dinner: No.1: Oyster Cocktails in Green Pepper Shells, Celery, Ripe Olives, Roast Goose with Potato Stuffing, Apple Sauce, String Beans, Potato Puff, Lettuce Salad with Riced Cheese and Bar-le-Duc French Dressing, Toasted Wafers, English Plum Pudding, Bonbons, Coffee. No.2: Cream of Celery Soup, Bread Sticks, Salted Peanuts, Stuffed Olives, Roast Beef, Yorkshire Pudding, Potato Soufflé, Spinach in Eggs, White Grape Salad with Guava Jelly, French Dressing, Toasted Crackers, Plum Pudding, Hard Sauce, Bonbons, Coffee.

Christmas Dinner: No.1: Oyster Cocktails in Green Pepper Shells, Celery, Ripe Olives, Roast Goose with Potato Stuffing, Apple Sauce, String Beans, Potato Puff, Lettuce Salad with Riced Cheese and Bar-le-Duc French Dressing, Toasted Wafers, English Plum Pudding, Bonbons, Coffee. No.2: Cream of Celery Soup, Bread Sticks, Salted Peanuts, Stuffed Olives, Roast Beef, Yorkshire Pudding, Potato Soufflé, Spinach in Eggs, White Grape Salad with Guava Jelly, French Dressing, Toasted Crackers, Plum Pudding, Hard Sauce, Bonbons, Coffee. Alva decided to attend a meeting of the Society for the Betterment of Working Children, which Armide had joined not long before. The group met once each month at the home of its president. Miss Annalisa Beekman was a young Knickerbocker lady whose pale eyes and pale hair and pale skin made her vulnerable to disappearance if she stood too near draperies or wallpaper of similar tones. Alva joined her and some ten other young ladies in the Beekman drawing room, which looked out onto Tenth Street. Among those ten: Lydia Roosevelt, who upon seeing Alva assessed her figure and said, “Well, Mrs. Vanderbilt, who would have expected you here?”

Alva decided to attend a meeting of the Society for the Betterment of Working Children, which Armide had joined not long before. The group met once each month at the home of its president. Miss Annalisa Beekman was a young Knickerbocker lady whose pale eyes and pale hair and pale skin made her vulnerable to disappearance if she stood too near draperies or wallpaper of similar tones. Alva joined her and some ten other young ladies in the Beekman drawing room, which looked out onto Tenth Street. Among those ten: Lydia Roosevelt, who upon seeing Alva assessed her figure and said, “Well, Mrs. Vanderbilt, who would have expected you here?”