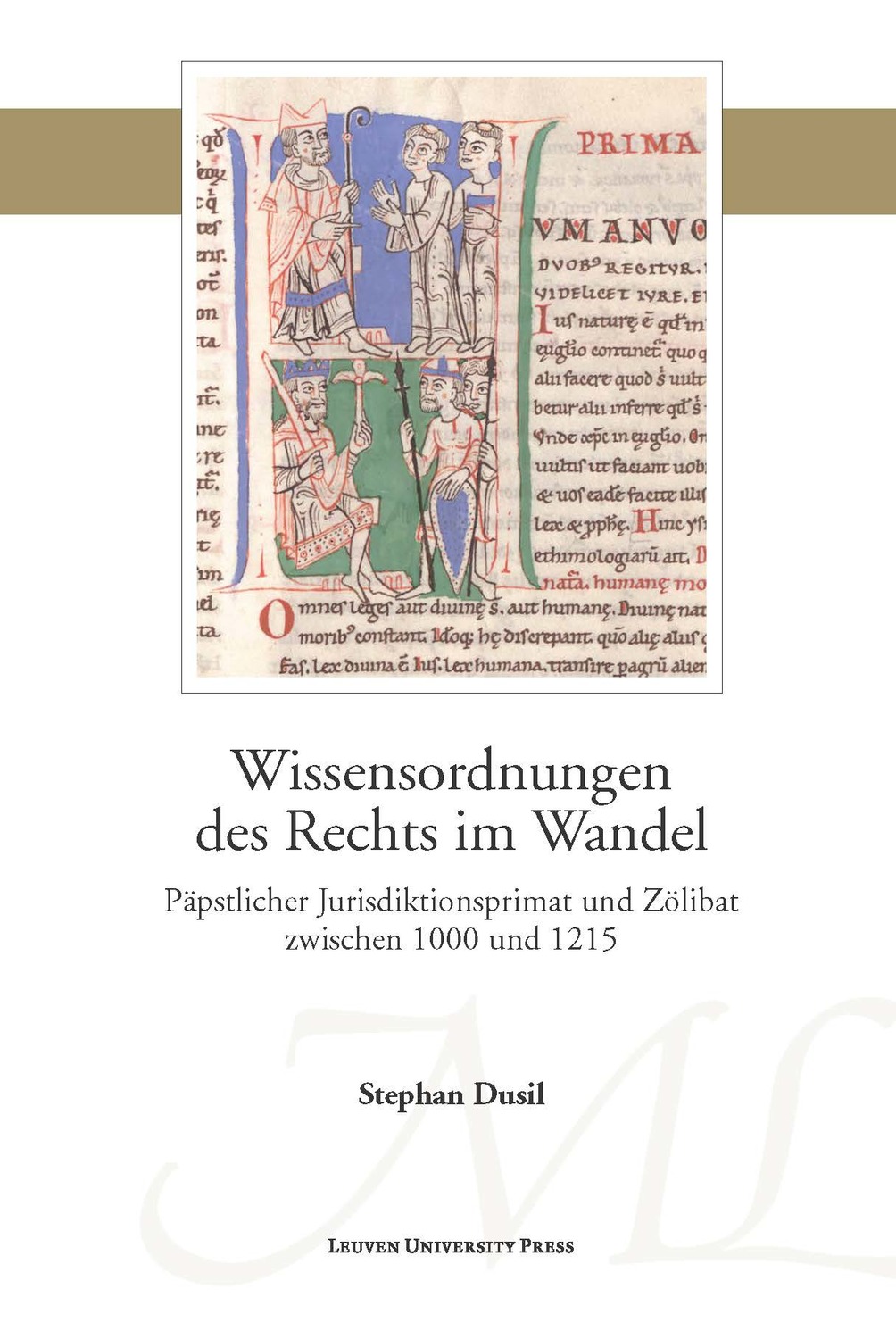

After 1000, work began in earnest to develop Canon Law into a fully developed complex legal system and academic discipline. New book tells the story by following the cases of papal jurisdictional primacy and clerical celibacy.

Wissensordnungen des Rechts im Wandel

Päpstlicher Jurisdiktionsprimat und Zölibat zwischen 1000 und 1215

By Stephan Dusil

Series: Mediaevalia Lovaniensia – Series 1-Studia 47

Leuven University Press 2018

Abstract:

Between 1000 and 1215, the knowledge of canon law changed fundamentally. Although ecclesiastic rules of law had been linearly collected by 1000, they had evolved into complex, highly interlinked carriers of knowledge by 1215. By carefully examining manuscript transmission, this book elucidates the evolution of legal knowledge, taking papal jurisdictional primacy and clerical celibacy as an illustrative example. Furthermore, it shows the influence the artes liberales and rhetoric had on the organisation of canon law. This study thus offers fascinating insights into the origins of canon law as an academic discipline, thereby also demonstrating the diversity and multi-layeredness of legal knowledge in the High Middle Ages. (This publication is GPRC-labeled (Guaranteed Peer-Reviewed Content).

About the Author:

Stephan Dusil is a professor of the Faculty of Law at KU Leuven.

Table of Contents

Vorwort

Vorwort

Einleitung

Kapitel 1: Wissen über Jurisdiktionsprimat und Zölibat. Fragestellung und methodischer Ansatz

1. Zum Begriff des Wissens

a) Ausgangsbefunde: Ansätze in den Geisteswissenschaften

b) Zuspitzung: Rechtswissen in der historischen Kanonistik

2. Untersuchungsfelder: Päpstlicher Jurisdiktionsprimat und Zölibat

a) Tu es Petrus: Der Jurisdiktionsprimat des Bischofs von Rom im mittelalterlichen Kirchenrecht

(1) Ausgangspunkt: Der Jurisdiktionsprimat im heutigen Kirchenrecht

(2) Rückblick: Die Herausbildung des Jurisdiktionsprimats bis zum Hochmittelalter

α) Die frühe Kirche

β) Ansätze zur primatialen Verdichtung

γ) Frühmittelalterliche Entwicklungslinien

δ) Die Durchsetzung des Jurisdiktionsprimats im Hochmittelalter

ε) Zusammenfassende Überlegungen

(3) Konkretisierung: Der Jurisdiktionsprimat als Untersuchungsgegenstand

b) propter regnum caelorum: Der Zölibat im mittelalterlichen Recht

3. Wissensordnungen im Wandel: Entwicklung der Fragestellung aus der Perspektive der historischen Kanonistik

Kapitel 2: Ausgangspunkt: Kanonessammlungen im 11. Und 12. Jahrhundert

1. Quellenkunde: Vorgratianische Kanonessammlungen

2. Primus liber continet: Die Darstellung des Jurisdiktionsprimats und des Zölibats in vorgratianischen Sammlungen

a) primae sedis episcopus aut princeps sacerdotum? Der Jurisdiktionsprimat zwischen episkopal-dezentraler und römisch-primatialer Perspektive

(1) Das Decretum Burchards von Worms

(2) Die Collectio 74 Titulorum

(3) Die Panormia

(4) Die Collectio Canonum Deusdedits

(5) Wissensproduktion im Wandel: Resümierende Beobachtungen

b) ut de carnali fiat spiritale coniugium: Der Zölibat

(1) Das Decretum Burchards von Worms

(2) Die Collectio 74 Titulorum

(3) Die Panormia

(4) Konstante Wissensbestände: Zusammenfassende Gedanken

c) Wandel und Konstanz kirchlichen Rechtswissens im 11. und 12. Jahrhundert: Jurisdiktionsprimat und Zölibat im Vergleich

3. Die Formierung juristischen Wissens. Zu Texteingriffen, Rubriken und Ordnungskonfigurationen

a) Methodische Beobachtungen zum Umgang mit Kanones

(1) Das Decretum Burchards von Worms

α) Kanones zum Jurisdiktionsprimat

β) Kanones zum Zölibat

(2) Die Collectio 74 Titulorum

α) Kanones zum Jurisdiktionsprimat

β) Kanones zum Zölibat

(3) Die Panormia

α) Kanones zum Jurisdiktionsprimat

β) Kanones zum Zölibat

(4) Die Collectio Canonum Deusdedits

b) aliter se habet orientalium traditio ecclesiarum, aliter huius sancte Romane ecclesie.Vom Texteingriff zur Interpretation?

4. mihi canones facere non licet? Zur Reflexion des Umgangs mit normativen Texten

a) Prologe zu Kanonessammlungen als Spiegel der Ordnungsvorstellungen der Kompilatoren

(1) colligere: Das Vorwort zum Decretum Burchards von Worms

(2) discretio: Die Praefatio zur Collectio Canonum des Deusdedit

(3) dispensatio: Der Prolog Ivos von Chartres

b) Von Sammlern und Interpreten: Resümierende Beobachtungen

Kapitel 3: Die gemachte und die gedachte Ordnung. Ordnungsvorschläge und ihre Umsetzung

1. Die gedachte Ordnung

a) Ein hinführendes Beispiel: Bernold von Konstanz

b) Bausteine des Ordnens

(1) Isagoge und inventio: Zum Lektürekanon und zur Schulbildung im 11. und 12. Jahrhundert

(2) Schweinehirt und König: Zur Verwendung dialektischer und rhetorischer Figuren im normativen Kontext

(3) circumstantia: Autoritätskonstruktion und Autoritätsrelativierung

(4) exempla: Zur Verwendung historischer Beispiele

(5) dispensatio und necessitas: Das Abweichen von der Norm als Standard

(6) auctoritates: Hierarchie als Ordnung

c) diversi, sed non adversi: Zusammenfassende Überlegungen

2. Die gemachte Ordnung

a) Ein hinführendes Beispiel: Bernold von Konstanz liest Burchard von Worms

b) Zur Überarbeitung älterer Sammlungen

(1) Zwischen Erhaltung und Adaption. Zur inhaltlichen Rezeption von Jurisdiktionsprimat und Zölibat

α) Das Decretum Burchards von Worms

β) Die Collectio 74 Titulorum

αα) Konstanz und Wandel

ββ) Ein neuer Entwurf? Zur Redaktion der schwäbischen Version

γγ) Überarbeitung oder neue Sammlung? Zu einigen Derivaten der Collectio 74 Titulorum

γ) Die Panormia

δ) Appendizes – ein Sonderfall?

αα) Das Decretum Burchard von Worms

ββ) Die Collectio 74 Titulorum

γγ) Die Panormia

δδ) Zusammenfassende Beobachtungen

ε) Zur Tradition der Ordnung: Bilanzierende Überlegungen

(2) Notandum quod… Überarbeitungen älterer Kanonessammlungen in methodischer Hinsicht

c) Neues Ansetzen? Die Collectio Trium Librorum, der Polycarpus sowie Bonizos De vita christiana und Algers De misericordia et iustitia

(1) Die Collectio Trium Librorum und der Polycarpus

(2) Bonizos von Sutri Liber de vita christiana

(3) Algers von Lüttich De misericordia et iustitia

(4) Vom Aufbrechen der Gattungen: Zusammenfassende Überlegungen

3. Zwischen Theorie und Praxis: Bilanz

Kapitel 4: Eine janusköpfige Kompilation? Das Decretum Gratiani

1. Quellenkunde: Das Decretum Gratiani

a) Die vielen Gratiane

b) Zur Überlieferung des Decretum Gratiani

(1) Die erste Version (Gratian 1)

(2) Die zweite Version (Gratian 2)

2. Wandel und Beharrung: Die Darstellung des Jurisdiktionsprimats und des Zölibats

a) Der Jurisdiktionsprimat

(1) Eine Bleistiftskizze: Gratian 1

(2) Ein farbenprächtiges Gemälde: Gratian 2

b) Konstanz statt Wandel? Der Zölibat

3. Beobachtungen zur Methode Gratians

a) Vom perspektivischen Argumentieren zur ausführlichen Darstellung: Der Jurisdiktionsprimat

(1) Das normative Grundgerüst: Gratian 1

(2) Die umfassende Ausformung: Gratian 2

b) Vom Ordnen und Zerstören: Der Zölibat

(1) Ordnen nach causa, tempus, locus: Gratian 1

(2) Assoziieren und Abschweifen: Gratian 2

c) Von Wissensspeichern und kommentierten Autoritäten: Zusammenfassende Überlegungen

4. Die Einheit der Ordnungen. Eine Bilanz

a) Struktur, inhaltliche Erschliessung und dicta

b) Dialektik und Kanonistik. Zur Aufnahme rhetorischer und dialektischer Techniken

c) Die Autorität zur Autoritätsrelativierung. Isidor als Argument für relative Rechtsgeltung

d) Vorläufer und Einflüsse

e) Nochmals: Die gemachte und die gedachte Ordnung

Kapitel 5: Relationales Rechtswissen. Kanonistik zwischen Kanonessammlungen und Glossa ordinaria

1. Die Unterwerfung des Decretum Gratiani: Die Dekretistik

a) Quellenkunde: Dekretistische Literatur

b) Beobachtungen zu Summen und Glossen

(1) Apparat-Summen: Die Summa Quoniam in omnibus, die Summe Rufins und die Summa Parisiensis

α) Inhaltliche Aussagen zu Jurisdiktionsprimat und Zölibat

β) Apparat-Summen: Eine Mischform der Wissensvermittlung?

(2) Synthese pur? Die Summa Coloniensis

(3) infra ix questione iii aliorum. Einige Beobachtungen zu Glossen

c) Im Spinnennetz des Rechtswissens. Zusammenfassende Überlegungen

2. Die Eroberung der Tradition? Ältere Ordnungsvorstellungen und dekretistischer Neuansatz

a) Steinbrüche. Burchard von Worms als Normlieferant

b) Die einheitliche Wissensordnung. Burchard und Gratian als Argument

c) Die Verwissenschaftlichung des Unwissenschaftlichen: Glossen in vorgratianischen Sammlungen

d) Verweigerungen? Vom Vorteil thematischer Sammlungen

e) Resümierende Beobachtungen

3. Juristisches Experimentieren in einer Transformationsphase: Zusammenführende Überlegungen

Kapitel 6: Rechtswissen im langen 12. Jahrhundert

1. Rückblick

a) Ordnung, Recht, Wissen. Konzepte und Ansätze

b) Vom Kommen und Gehen kanonistischer Diskurse

c) Transformationen der Wissensstruktur

2. Ausblick

a) Mise-en-page und medialer Wandel

b) Von Monstern, die in Doppeltexten leben

c) Vom Kompilator zum Autor – und zurück?

d) Strukturwandel des Rechtswissens im langen 12. Jahrhundert

Anhang

Abkürzungsverzeichnis

Handschriftenstudien

1. Siglenverzeichnis

2. Appendix zur Collectio 74 Titulorum im Manuskript Florenz, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Pluteus 16 cod. 15

3. Glossen zur Collectio 74 Titulorum

Verzeichnis benutzter Quellen und Literatur

1. Ungedruckte Quellen

2. Gedruckte Quellen

3. Lexika, Wörterbücher, Handschriftenkataloge und andere Hilfsmittel

4. Literatur

Register der Handschriften

Register der Personen

Register der Textsammlungen

Register der Textstellen (Konzilien, Dekretalen, sonstige Texte)

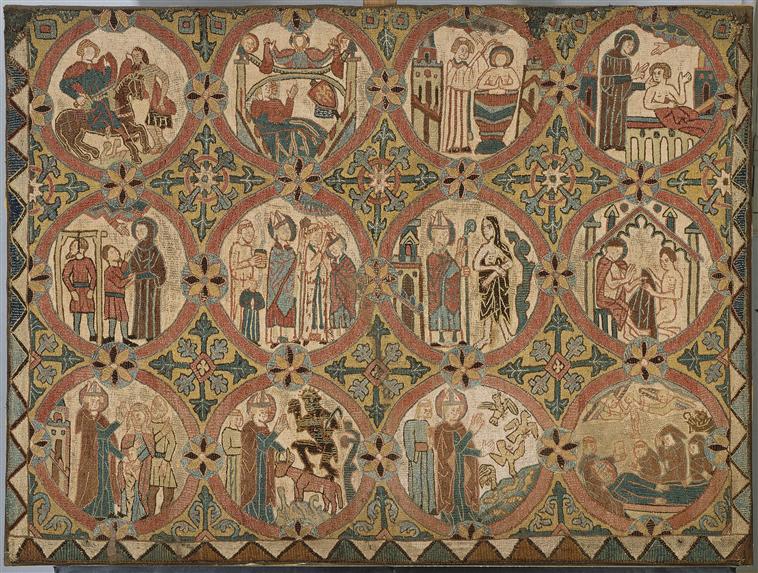

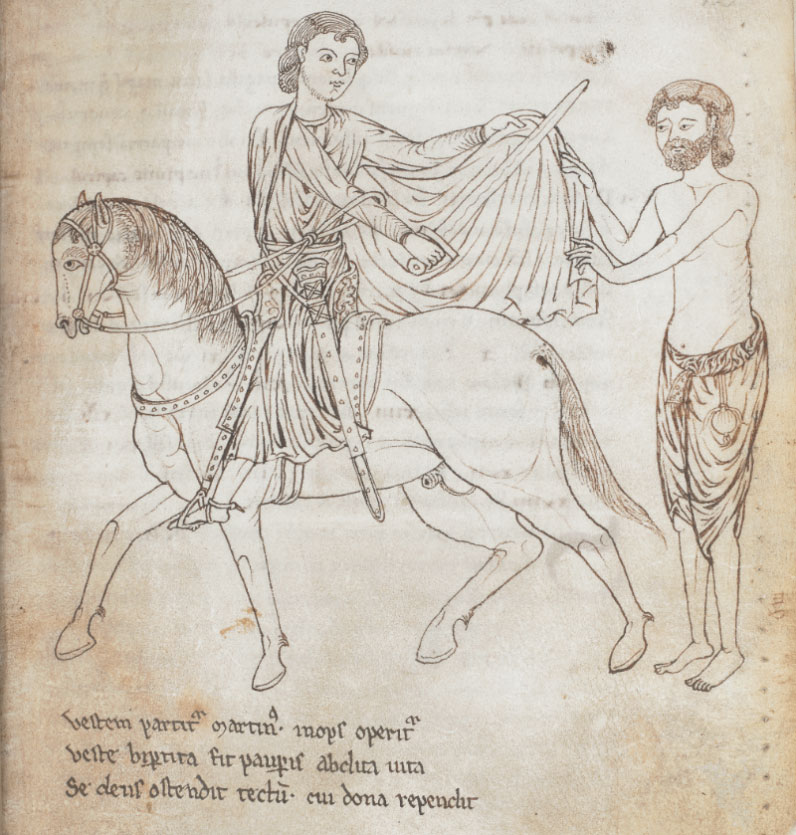

FEATURED PHOTO:

Bible Moralisé. MS. Bodl. 270b fol. 208r 13th century, middle © Digital Bodleian

The post The Development of Canon Law in the High Middle Ages appeared first on Medieval Histories.

Powered by WPeMatico

Mexico City’s American Legion post in a charming old house in the leafy Condessa district is one of the few places the fliers are remembered. The post is a comfortable relic of another time, with a bar that opens at 2:00 p.m., a used bookstore, and memorabilia adorning the walls, including a photo of poet Alan Seeger—uncle of American folk singer Pete Seeger—who died at the Battle of the Somme in World War I. A secretary named Margarita dug out photos of the handsome young men of the Aztec Eagles for me. In some they posed with the propeller aircraft they flew, Thunderbolt single-seat fighters. In the past, Margarita said, the post hosted celebrations on Veterans Day—11/11 at 11:00 a.m.—“for those who came back alive.” On Memorial Day, the Aztec Eagles joined American Legionnaires and U.S. Marines from the embassy at a cemetery to honor the dead. Mostly, however, the fliers were forgotten warriors in a country where the man on the street had little interest in the Second World War—even though Mexico had played an important part in supplying manpower to replace U.S. agricultural workers gone to fight, and providing oil and other natural resources.

Mexico City’s American Legion post in a charming old house in the leafy Condessa district is one of the few places the fliers are remembered. The post is a comfortable relic of another time, with a bar that opens at 2:00 p.m., a used bookstore, and memorabilia adorning the walls, including a photo of poet Alan Seeger—uncle of American folk singer Pete Seeger—who died at the Battle of the Somme in World War I. A secretary named Margarita dug out photos of the handsome young men of the Aztec Eagles for me. In some they posed with the propeller aircraft they flew, Thunderbolt single-seat fighters. In the past, Margarita said, the post hosted celebrations on Veterans Day—11/11 at 11:00 a.m.—“for those who came back alive.” On Memorial Day, the Aztec Eagles joined American Legionnaires and U.S. Marines from the embassy at a cemetery to honor the dead. Mostly, however, the fliers were forgotten warriors in a country where the man on the street had little interest in the Second World War—even though Mexico had played an important part in supplying manpower to replace U.S. agricultural workers gone to fight, and providing oil and other natural resources.