by Andrew Grant Jackson

More than half a century ago, friendly rivalry between musicians turned 1965 into the year rock evolved into the premier art form of its time and accelerated the drive for personal freedom throughout the Western world.

The Beatles made their first artistic statement with Rubber Soul. Bob Dylan released “Like a Rolling Stone, arguably the greatest song of all time, and went electric at the Newport Folk Festival. The Rolling Stones’s “Satisfaction” catapulted the band to worldwide success. New genres such as funk, psychedelia, folk rock, proto-punk, and baroque pop were born. Soul music became a prime force of desegregation as Motown crossed over from the R&B charts to the top of the Billboard Hot 100. Country music reached new heights with Nashville and the Bakersfield sound. Musicians raced to innovate sonically and lyrically against the backdrop of seismic cultural shifts wrought by the Civil Rights Movement, Vietnam, psychedelics, the Pill, long hair for men, and designer Mary Quant’s introduction of the miniskirt.

In 1965, Andrew Grant Jackson combines fascinating and often surprising personal stories with a panoramic historical narrative. Keep reading for an excerpt.

* * * * *

Per rock critic Richie Unterberger, the earliest-known use of the term folk rock was in a Billboard cover story on June 12, “Folkswinging Wave On—Courtesy of Rock Groups,” by Eliot Tiegel, who used the term to describe the Byrds, Sonny and Cher, the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Rising Sons, Jackie DeShannon, and Billy J. Kramer.

Per rock critic Richie Unterberger, the earliest-known use of the term folk rock was in a Billboard cover story on June 12, “Folkswinging Wave On—Courtesy of Rock Groups,” by Eliot Tiegel, who used the term to describe the Byrds, Sonny and Cher, the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Rising Sons, Jackie DeShannon, and Billy J. Kramer.

It was around that time that Dunhill Records owner Lou Adler gave a copy of Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home to one of his songwriters, P. F. Sloan, and told him to come up with a Dylanesque protest single for the Byrds. Between midnight and dawn, “Eve of Destruction” came to Sloan in a torrent.

He was nineteen, old enough to be sent to Vietnam but not old enough to vote yet (the voting age was twenty-one in all but four states), the same injustice Eddie Cochran sang about in 1958 in “Summertime Blues,” except now there was a war on. Sloan was still haunted by the pounding martial drums from President Kennedy’s funeral and worked those in, along with fears of nuclear apocalypse. He decried the hypocrisy of calling the Communists hateful while the Klan murdered in the South and congressmen dithered.

The Byrds. Image is in the public domain via Wikipedia.

The Byrds rejected the song, though, so Sloan pitched it to Byrds imitators the Tyrtles (later, simply, Turtles) backstage at the Sunset Strip club the Crescendo (later the Trip). Howard Kaylan recalled, “Our jaws hit the ground. We all knew that it would be a monster hit, it was that powerful. But we also knew that whoever recorded this song was doomed to have only one record in their/his career. You couldn’t make a statement like that and ever work again.”

But a growly singer named Barry McGuire was looking for work after leaving the New Christy Minstrels in January. Byrd Gene Clark had once been in the Christys, so he invited McGuire to come watch them play at Ciro’s. After the Byrds’ performance, McGuire led a conga line into the street. Dunhill’s Lou Adler was there, and the two started talking about working together.

On Thursday, July 15, McGuire went into the studio with Sloan on six-string and harp, alongside two of LA’s top session men, drummer Hal Blaine and bassist Larry Knechtel of the Wrecking Crew. McGuire recorded Sloan’s “What Exactly’s the Matter with Me” and needed a B side. They had ten minutes of studio time left, just enough to lay down one take of “Eve of Destruction.” McGuire read the lyrics off the wrinkly paper on which Sloan had written them, building to a rage for the climax in which he bitterly reminds Selma, Alabama, not to forget to say grace while they bury their murdered black neighbors.

Sloan’s writing-producing partner, Steve Barri, took a copy of the tape with him so he could listen to it in his office the next day. The president of Dunhill, Jay Lasker, heard it and took the tape to listen to it again himself. A few hours later, Lou Adler burst into the office, enraged. “Eve of Destruction” was playing on the radio, in what Adler believed was a completely unpolished form.

Lasker had instructed a promo man to take the tape down to radio station KFWB to find out if it was too controversial to air. The program director was so exhilarated by the track that he played it on air immediately, and it became their most requested song since “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Adler initially thought McGuire needed to redo his vocals—after all, the singer had had trouble reading Sloan’s handwriting—but in the end, Adler simply added a ghostly female background choir to make it sound less like a rough mix. Just as “Like a Rolling Stone” was doing that same July, the song had bypassed the gatekeepers. “Eve” would make it to No. 1 on September 25, as the kids across the country returned to school. Ironically, it would block its inspiration, Dylan, from rising above No. 2.

In October a group called the Spokesmen—comprised of a deejay and two of the songwriters responsible for “At the Hop,” Lesley Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me, and “1-2-3,” by Len Barry—issued “Dawn of Correction,” their answer to “Eve of Destruction.” The song made it to No. 36 on October 16, with lyrics affirming that Americans needed to keep the world free from Communists and that the A-bomb was ultimately good because it fostered negotiation. The song pointed to progress in voter registration, vaccination, the United Nations, and decolonization. (Luckily for the writers, these all rhymed.)

Sloan’s reaction was “This is great! Maybe it’s a dialogue happening: via the radio via musical recordings.” Sonny Bono sang in “The Revolution Kind” that men weren’t necessarily radicals just because they spoke their minds (which he would prove when he became a Republican congressman in 1994). “It’s Good News Week,” by Hedgehoppers Anonymous, took the black comedy approach for their knockoff, in which nukes reanimate the rotting dead.

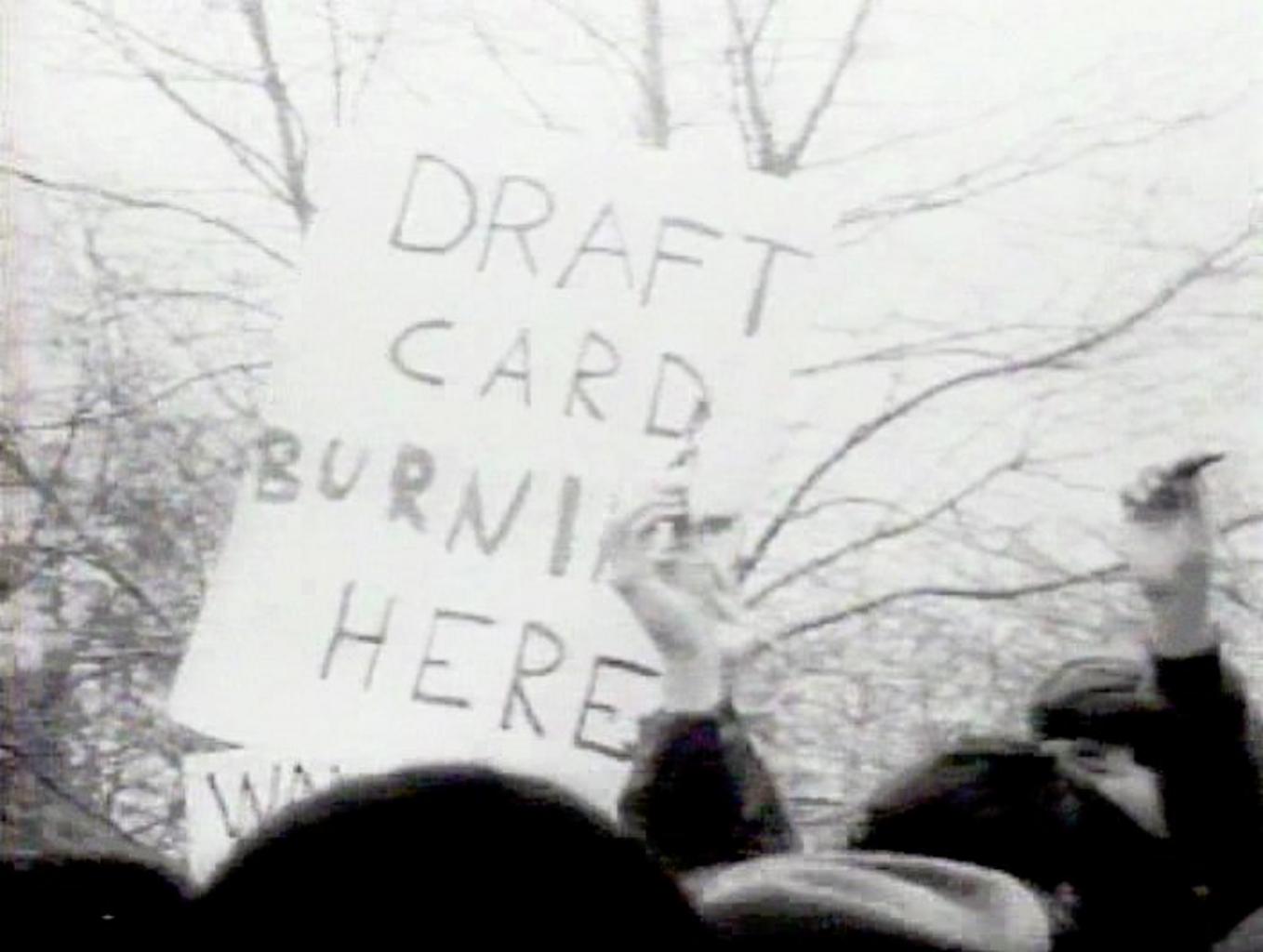

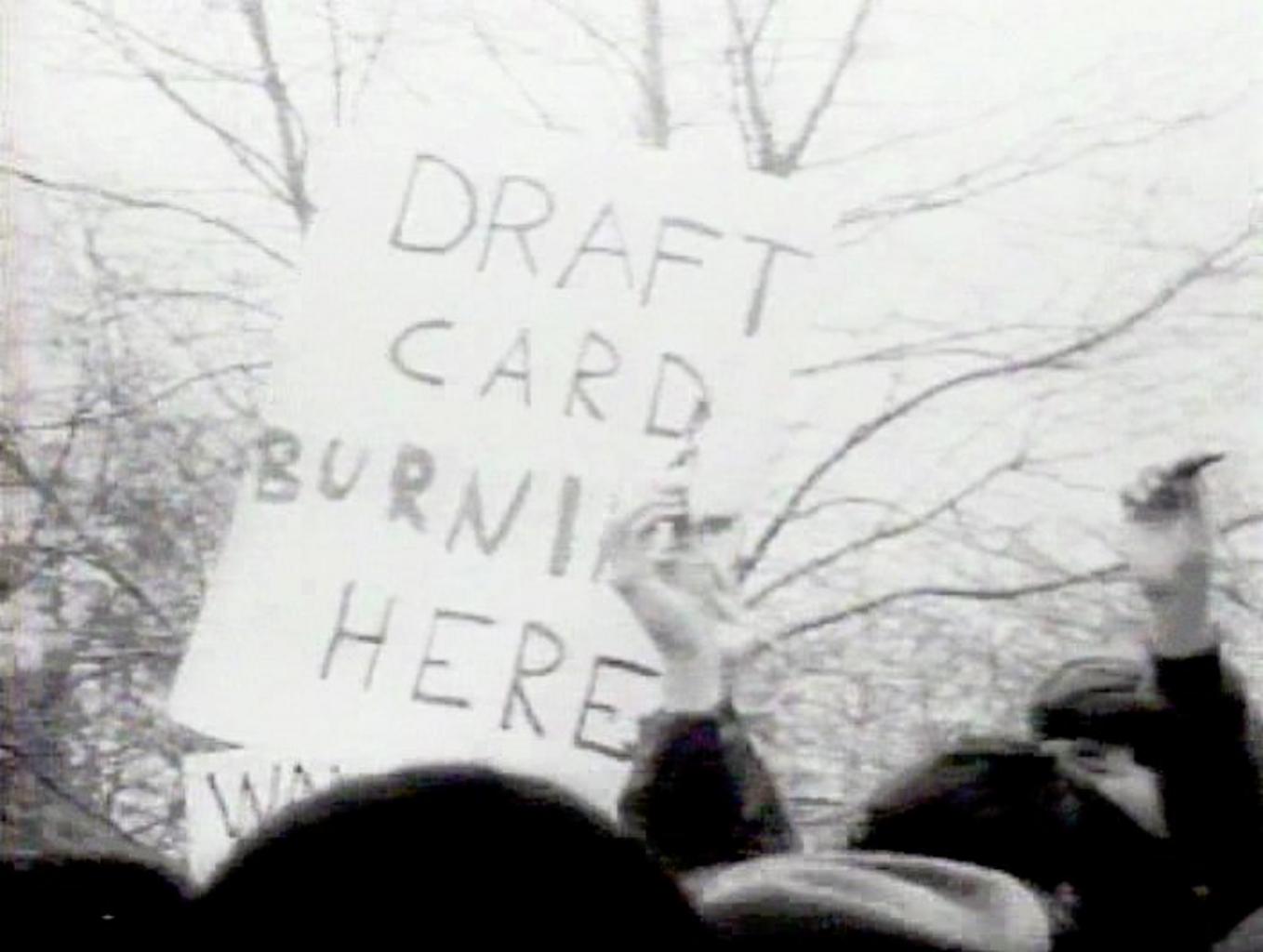

Now that Dylan had left topical protest behind, Phil Ochs stepped in with “Draft Dodger Rag.” Ochs’s “I Ain’t Marching Anymore” was an epic account of the history of U.S. warfare in two minutes and thirty-five seconds, and he even tried his own electric version, though the acoustic original has more grace. Tom Paxton sang “Lyndon Johnson Told the Nation” and, in “We Didn’t Know,” equated the Americans who turned a blind eye to Jim Crow and Vietnam with “good Germans” ignoring the Holocaust during World War II. The Chad Mitchell Trio sang “Business Goes on as Usual,” in which the economy booms while the singer’s brother dies in a war he doesn’t understand.

Anti-war protest in New York City in 1967, including a group of young men burning their draft cards. Image is in the public domain via Wikipedia.

Both English folkie Donovan and Glen Campbell, the session guitarist struggling to become a country-pop star in his own right, covered Buffy St. Marie’s “Universal Soldier.” (On the flip side, Donovan covered Mick Softley’s “The War Drags On.”) Campbell seems to have been caught unaware by the antiwar slant of the lyrics, and by October he was telling journalists, “The people who are advocating burning draft cards should be hung. If you don’t have enough guts to fight for your country, you’re not a man.” He was perhaps stung by the Jan and Dean answer song, “The Universal Coward.”

On the country front, neither Loretta Lynn’s “Dear Uncle Sam” or Willie Nelson’s “Jimmy’s Road” offered an opinion on the war itself. Rather, the songs focused on the death of a husband and a friend, respectively. However, Dave Dudley’s “What We’re Fighting For” and Johnnie Wright’s “Hello Vietnam” were the pro-war anthems to be expected from the country and western genre. The latter song said that we had to learn to put out fires before they got too big, alluding to how the Allies had avoided going to war with Hitler for years, allowing him the time to grab more countries, implying we couldn’t afford to do the same thing again with the Soviets and China. The writer of “Hello Vietnam,” Tom T. Hall, also wrote a female version called “Good-Bye to Viet Nam,” in which Kitty Hawkins sings how she just got news her man is coming back home to her.

Staff sergeant Barry Sadler of the Green Berets was a combat medic in Vietnam wounded by the booby trap stake called the Punji stick.11 In the hospital, he wrote twelve verses of “The Ballad of the Green Berets.” The author of a book called The Green Berets, Robin Moore, helped Sadler edit the song down. It was recorded late in the year, for the military, and was so popular that it leaked out, and RCA decided to release it. It sold a million copies in two weeks and topped the charts on March 5, becoming the No. 1 single of 1966.

A few weeks after “Eve of Destruction” itself leaked out, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles detonated into flames. Though it’s impossible to say how many of its residents listened to the lyrics of a white folk-rock single, the song’s rage at the state of race relations grew even more disturbing when the rioters began torching white-owned stores. LA disc jockey Bob Eubanks asked, “How do you think the enemy will feel with a tune like that No. 1 in America?”

Sloan said that Dunhill Records received death threats. McGuire said, “‘Eve of Destruction’ was a scary song because it made it on its own; it had no ‘payola,’ no disc jockey manipulation. Phil [Sloan] told me later on that there was a letter that went out from The Gavin Report [the trade magazine for radio programmers] or something saying, ‘No matter what McGuire puts out next, don’t play it.’ . . . Because their feeling was that I was like a loose cannon in the record industry, and they wanted to get me back in line.”

It was a shame, because McGuire’s other Sloan-penned tracks are terrific. “What Exactly’s the Matter with Me” mines the same ennui that the Mike Nichols film The Graduate would two years later. McGuire bemoans the futility of going to college just to get a job to buy a TV, but admits he can’t march because he’s too insecure. “Child of Our Times” expresses his worry for children being born into the “Eve of Destruction.” Its B side, “Upon a Painted Ocean” is an invigorating mash-up of Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changin’” and “When the Ship Comes In,” its title borrowed from eighteenth-century British poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”

In the wake of the success of “Eve of Destruction,” P. F. Sloan got to release his own solo singles. “Sins of a Family” was another of the songs he wrote that night while listening to Dylan. It was certainly the catchiest folk-rock ditty to beg compassion for the daughter of a schizo hooker. But Sloan’s pinnacle was “Halloween Mary,” which uses all Dylan’s tropes to sing the praises of a Sunset Strip scenester. (The title was itself probably inspired by a line in “She Belongs to Me.”)

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965 while Martin Luther King and others look on. Image is in the public domain via Wikipedia.

The Turtles made a passionate single out of Sloan’s “Let Me Be,” since, as lead singer Kaylan explained, it was “just the perfect level of rebellion . . . haircuts and nonconformity. That was as far as we were willing to go.” Sloan also wrote hits for Johnny Rivers, Herman’s Hermits, the Seekers, and the Grass Roots, but his career mysteriously faded after another year. Still, he could take solace in the fact that “Eve of Destruction” may have helped speed the passage of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment, which lowered the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen. Congressmen had attempted to lower the requirement during World War II, and President Eisenhower had backed a new constitutional amendment in 1953, but these efforts never passed. In 1969 the National Education Association began a new push with the help of the YMCA, the AFL-CIO, the NAACP, and U.S. congressmen, including Edward Kennedy. The Twenty-Sixth Amendment was ratified in 1971. Perhaps the fact that one of the biggest hits of the decade lamented being old enough to kill but not to vote was a crucial bit of agitprop that helped the campaign finally to succeed.

ANDREW GRANT JACKSON is the author of Still the Greatest: The Essential Songs of the Beatles’ Solo Careers, Where’s Ringo? and Where’s Elvis? He has written for Rolling Stone, Slate, Yahoo!, and PopMatters. He directed and co-wrote the feature film The Discontents starring Perry King and Amy Madigan. He lives in Los Angeles.

The post Folk Rock Explosion: Protest Music in Summer 1965 appeared first on The History Reader.

Per rock critic Richie Unterberger, the earliest-known use of the term folk rock was in a

Per rock critic Richie Unterberger, the earliest-known use of the term folk rock was in a

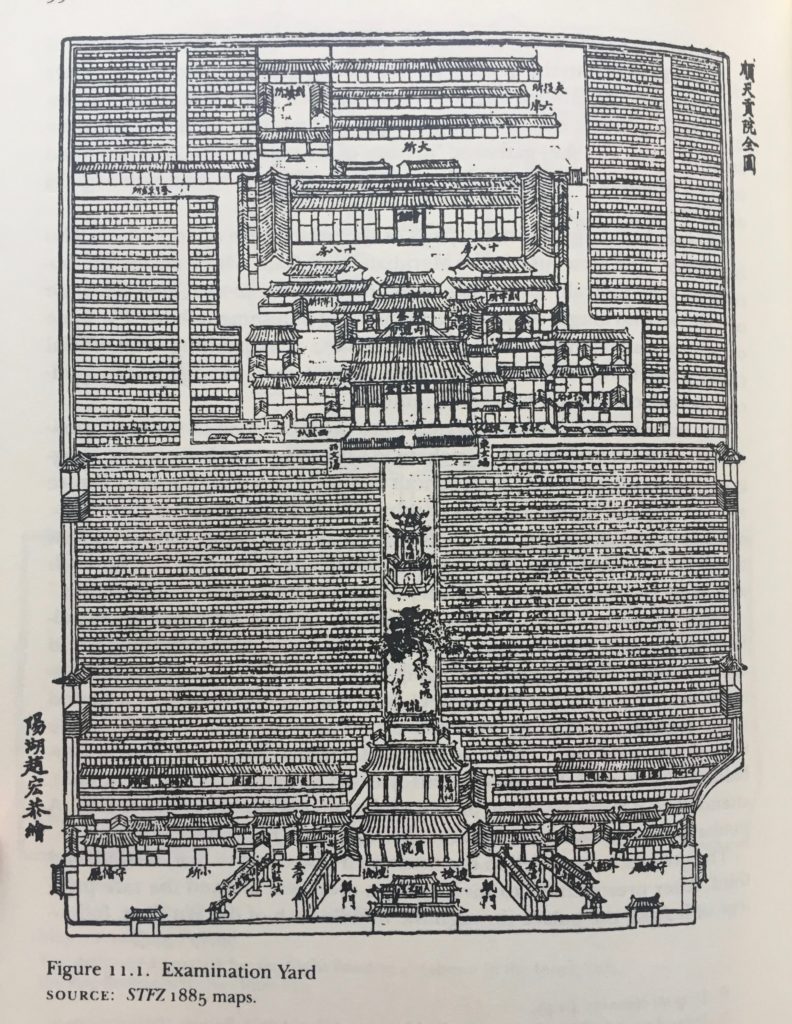

In the final hours before the exams commenced, commercial activity became concentrated around the examination complex located on the eastern edge of the city. Peddlers had one final opportunity to sell brushes, ink, food, and bedding before the candidates filed into the yard. Once inside, they were not permitted any contact with the outside world for three days. The complex contained thousands of identical cells divided by thin walls, but open to the sky. Within each tiny cell were two planks to be used as a seat, desk, and bed. More comfortable quarters were provided for the examiners and their clerks.

In the final hours before the exams commenced, commercial activity became concentrated around the examination complex located on the eastern edge of the city. Peddlers had one final opportunity to sell brushes, ink, food, and bedding before the candidates filed into the yard. Once inside, they were not permitted any contact with the outside world for three days. The complex contained thousands of identical cells divided by thin walls, but open to the sky. Within each tiny cell were two planks to be used as a seat, desk, and bed. More comfortable quarters were provided for the examiners and their clerks.

Jack branches out. He invests his Blood Alley profits and opens Riley’s Bamboo Hut up on the North Szechuen Road, not too far from the Venus—kind of a luau theme mixed with rattan furniture round the bamboo-lined walls, waitresses wearing Honolulu leis and not much else. North Szechuen in Hongkew is marginally classier than Blood Alley, though far from top drawer. Jack taps Nellie to get in some dancers who didn’t quite make the cut for the Follies; Joe finds him a band looking for a gig who can work up a few ukelele tunes to fit the theme. Hongkew is mostly out of bounds to squaddies and leathernecks, but not to officers. And so Jack covers the bases—the Manhattan coins it in from the leathernecks and the ranks; the Bamboo Hut gets the NCOs and the brass.

Jack branches out. He invests his Blood Alley profits and opens Riley’s Bamboo Hut up on the North Szechuen Road, not too far from the Venus—kind of a luau theme mixed with rattan furniture round the bamboo-lined walls, waitresses wearing Honolulu leis and not much else. North Szechuen in Hongkew is marginally classier than Blood Alley, though far from top drawer. Jack taps Nellie to get in some dancers who didn’t quite make the cut for the Follies; Joe finds him a band looking for a gig who can work up a few ukelele tunes to fit the theme. Hongkew is mostly out of bounds to squaddies and leathernecks, but not to officers. And so Jack covers the bases—the Manhattan coins it in from the leathernecks and the ranks; the Bamboo Hut gets the NCOs and the brass.

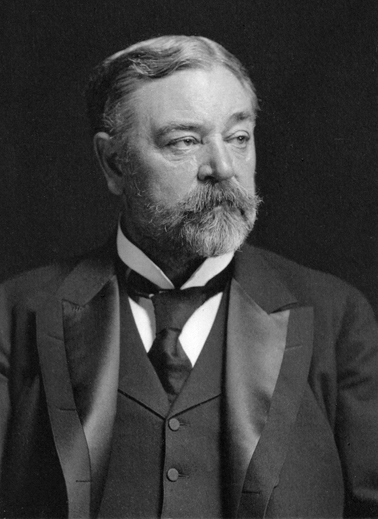

Robert attended the finest schools, such as Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard College, and Harvard Law School. By age twenty-one, he’d already attended both of his father’s presidential inaugurations. A year later, he left Harvard Law School to become the assistant adjutant to General Grant, a mere two months before the

Robert attended the finest schools, such as Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard College, and Harvard Law School. By age twenty-one, he’d already attended both of his father’s presidential inaugurations. A year later, he left Harvard Law School to become the assistant adjutant to General Grant, a mere two months before the  Yet sadness also followed Robert. He’d

Yet sadness also followed Robert. He’d  Robert made his last public appearance at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. in May 1922. He died at Hildene four years later, one week shy of his eighty-third birthday. Though he desired to be buried in the Lincoln Tomb in Springfield, Illinois, his wife interred him in a grand sarcophagus at Arlington Cemetery.

Robert made his last public appearance at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. in May 1922. He died at Hildene four years later, one week shy of his eighty-third birthday. Though he desired to be buried in the Lincoln Tomb in Springfield, Illinois, his wife interred him in a grand sarcophagus at Arlington Cemetery.