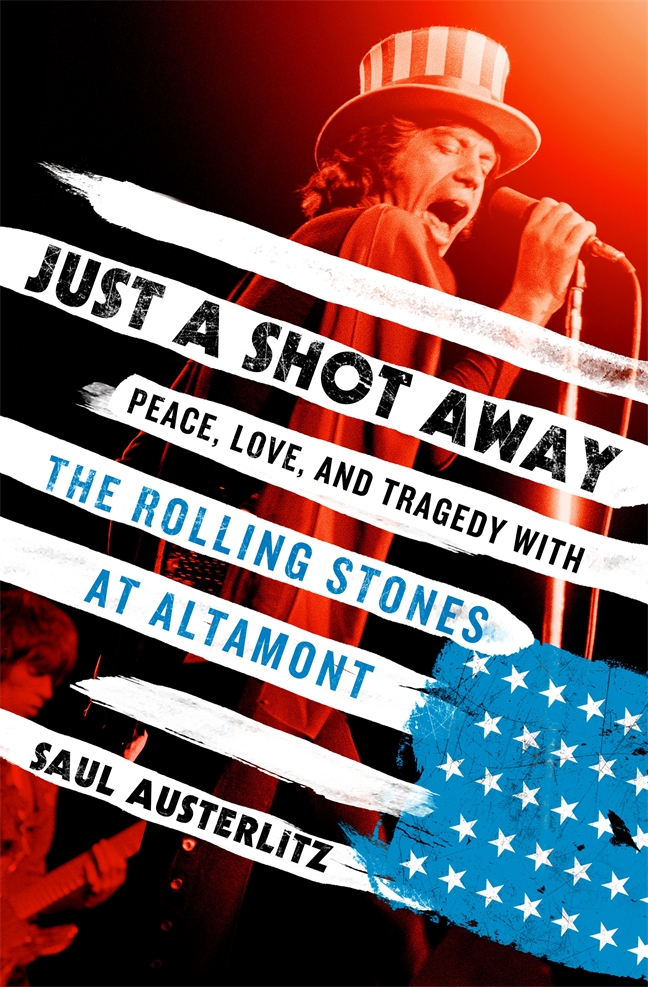

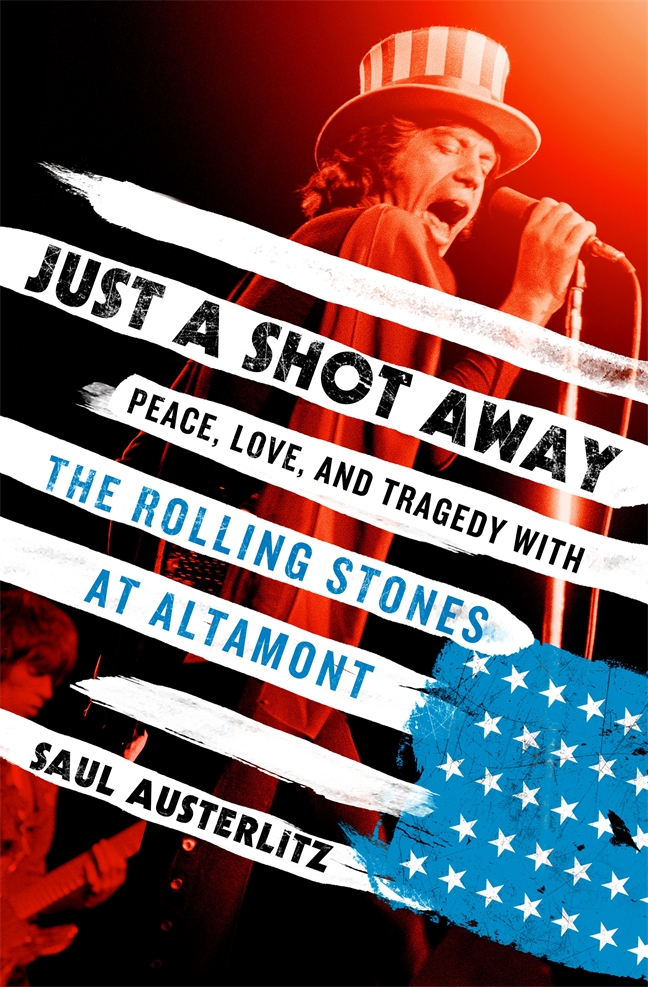

by Saul Austerlitz

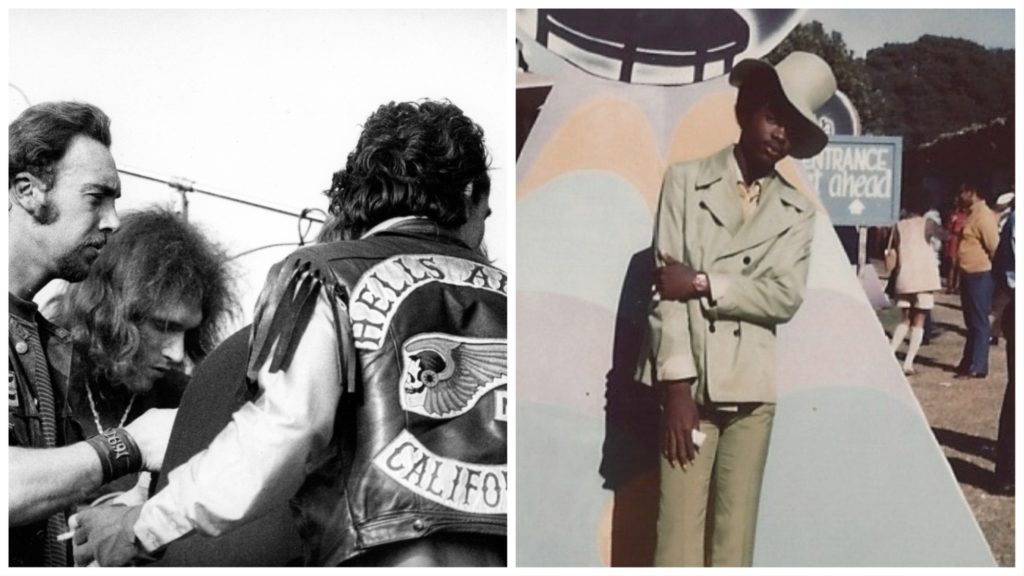

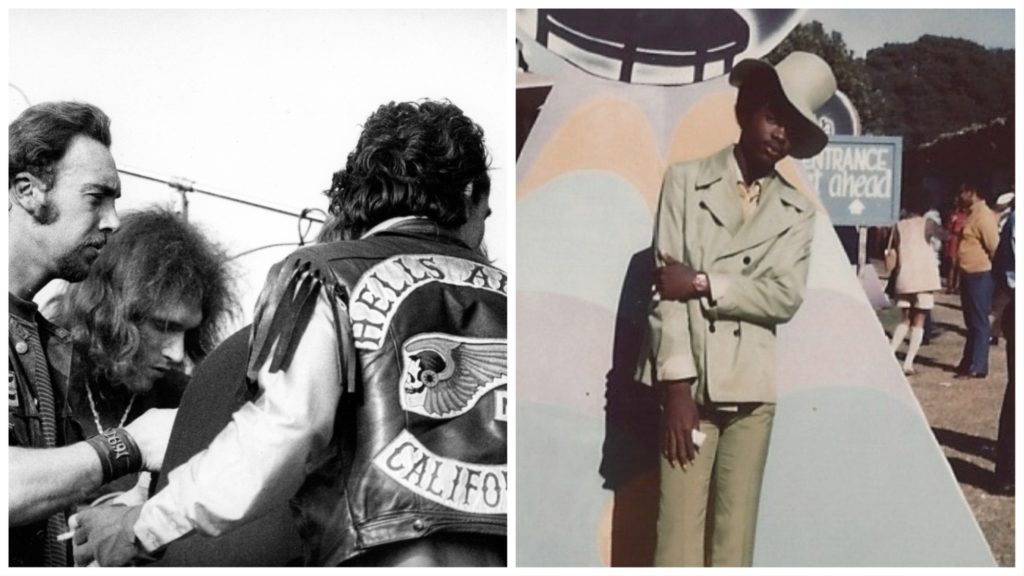

Puttering in mostly unnoticed among the stream of vehicles making their way onto the speedway grounds, a tan school bus crammed full of young men parked just behind the stage. From the exterior, this bus hardly differed from any of the other ramshackle vehicles to have arrived at Altamont that day. But unlike the majority of people attending, the men in the dun-colored bus had come to do a job. They were bikers, and the bus was owned by the San Francisco chapter of the Hells Angels. The vehicle containing the bulk of the security staff for Altamont rolled to a halt about one hundred yards away from the stage. The remainder of the Angels rode their Harleys—some solo and some with female passengers clinging to their backs—right up to the lip of the stage. The crowd frantically scattered out of the way of the sputtering motorcycles.

When the Hells Angels rode in to a new destination, they always followed a distinct pecking order. The full-fledged members would roar in on their motorcycles first, with the prospects, associates, and assorted hangers-on bringing up the rear. What was true of their entrances was true of all the bikers did. The members would always lead the way. The others, particularly the prospects who hoped to curry enough favor to join the club, would always follow the lead of their superiors.

There would be little oversight of the Hells Angels at the start of the concert, either from the festival staff or the Angels’ leaders. Few, if any, bikers present would be concerned with the long-term reputation of the Hells Angels, and how the broader public might perceive their actions. Oakland Angel chief Sonny Barger, perhaps the most respected (and feared) of the Bay Area Angels, was absent at the start of the concert, attending an officers’ meeting along with numerous other high-ranking Hells Angels. In their absence, the Angels dispatched many of their younger and more spirited members, along with prospects intent on proving their mettle under battle conditions.

On this day, there were approximately twenty or twenty-five Hells Angels present, with another few dozen prospects and hangers-on with them. The prospects, in particular, knew that the best way to win the Angels’ acceptance was with a demonstration of their unyielding toughness. With little police presence at Altamont, and almost no security presence besides the Hells Angels, bikers had carte blanche to strong-arm the audience. And as fans kept pushing forward from the back, those up front would get dangerously close to the Hells Angels and their motorcycles.

On this day, there were approximately twenty or twenty-five Hells Angels present, with another few dozen prospects and hangers-on with them. The prospects, in particular, knew that the best way to win the Angels’ acceptance was with a demonstration of their unyielding toughness. With little police presence at Altamont, and almost no security presence besides the Hells Angels, bikers had carte blanche to strong-arm the audience. And as fans kept pushing forward from the back, those up front would get dangerously close to the Hells Angels and their motorcycles.

Three hundred thousand people arrived at Altamont over the course of the morning and early afternoon, and the only protection they had from chaos was itself fomenting that very same chaos. There was no visible police presence, and little security beyond the Hells Angels, who, whatever services they might have provided in the past, were clearly uninterested in keeping the peace at Altamont. As the Angels took their places, a huge contingent of fans was attracted, as if by invisible magnets, into close proximity to the bikers, near the lip of the stage. They were impelled by an unconscious desire to be as close as possible to the Rolling Stones, and by the layout of the speedway itself. Everyone crept closer and closer, and for the people at the front, there was nowhere to go.

The raceway was enormous, and the stage tiny in comparison. From a distance, the figures on the stage were hardly more than dots, and fans who had made the trek from the Bay Area wanted to come home with firsthand reports of having seen Mick Jagger in the flesh. They began to push in. The fans already standing near the front were crunched ever closer to the stage. A tight-knit crowd became standing-room-only, and standing-room-only became not quite enough room to stand.

Some onlookers thought the whole scene resembled a New York subway car at rush hour. There you were, holding on to a strap, breathing in the fumes of someone’s wet armpits, and convinced it could not possibly get any more crowded. There simply was not room for another human being in this car. Then the train stopped at the next station, and another crush of human beings shoved their way on. Then the same scene repeated at the next stop, and the one after that. The fifty or sixty yards nearest the stage rapidly transformed into a carpet of people, a breathing mass of undifferentiated humanity too crammed together to separate. It was terrifying to be so closely packed in, to have one’s well-being be so thoroughly at the mercy of the crowd.

From the moment of the Angels’ arrival, violent conflicts broke out everywhere. Wherever bikers were, violence spontaneously erupted. If you asked the bikers themselves, they would tell you it was because their reputations preceded them. Everywhere they went, there would be someone with a hard-on for a biker, intent on kicking some Angel ass so they could go home and brag to all their friends. Detractors might argue that the bikers themselves treated violence as a blunt instrument, capable of dealing out punishment, retribution, or a much-needed lesson after a perceived infraction. Altamont was no different. Bikers grabbed women by the hair and assaulted them. They spotted attractive women in the crowd and yanked them up forcibly to the top of their bus. They snatched cameras out of fans’ hands and ripped out the film after being photographed without their permission. They threatened to kill concertgoers who accidentally stepped on their fingers. The bikers had established a closed system in which they were simultaneously the criminals and the police force tasked with preserving order. Those looking for justice would find nowhere to turn other than to those who had violated their trust.

Five-foot-seven and 175 pounds, all muscle from his day job as a roofer, “Hawkeye” came with three knives and a .22 revolver, in the mood to party and only too glad to hassle anyone who got in the way of his fun. Hawkeye and his friends from another motorcycle group, the Sons of Hawaii, had come with a fistful of counterfeit $20 bills they had printed at a local copy shop, planning to use them to buy drugs from sellers in the crowd. Upon arrival at Altamont, they realized there would be no need for such elaborate chicanery. He and his friends would steal money and drugs from those displaying their stashes or their bankrolls, and then violently manhandle them when they complained. The victims would almost inevitably head off to find their friends, and when they came back, spoiling for a fight, Hawkeye and his friends would beat them once more. The victims were scared, and desperate for a security presence to resolve the situation, but no authority was higher than that of the Hells Angels. Hawkeye didn’t worry about their complaints, or even their fitful attempts to get rough. Unless they came back with an army, they would have no chance at all. He and his friends were pushing people around, kicking ass, and stealing girlfriends, and having the time of their lives doing it.

Five-foot-seven and 175 pounds, all muscle from his day job as a roofer, “Hawkeye” came with three knives and a .22 revolver, in the mood to party and only too glad to hassle anyone who got in the way of his fun. Hawkeye and his friends from another motorcycle group, the Sons of Hawaii, had come with a fistful of counterfeit $20 bills they had printed at a local copy shop, planning to use them to buy drugs from sellers in the crowd. Upon arrival at Altamont, they realized there would be no need for such elaborate chicanery. He and his friends would steal money and drugs from those displaying their stashes or their bankrolls, and then violently manhandle them when they complained. The victims would almost inevitably head off to find their friends, and when they came back, spoiling for a fight, Hawkeye and his friends would beat them once more. The victims were scared, and desperate for a security presence to resolve the situation, but no authority was higher than that of the Hells Angels. Hawkeye didn’t worry about their complaints, or even their fitful attempts to get rough. Unless they came back with an army, they would have no chance at all. He and his friends were pushing people around, kicking ass, and stealing girlfriends, and having the time of their lives doing it.

The only thing missing for Hawkeye and his friends was a pad and a pencil. There were so many free-love girls there, all flashing their breasts and flirting outrageously with the bikers, that he later wished he had gotten some of their numbers for later use. This was a party, and they were the guests of honor. They never wanted it to end. Hawkeye and his friends felt free, unquestioned, even loved. They tossed some overzealous band handlers off the stage, and basked in the glow of the audience’s pleasure at seeing this literal leveling. The whole crowd laughed with them, or at least it felt that way for these young men, high on crank—a variant of methamphetamine— and their own authority.

Four or five plainclothes Alameda County sheriffs stood around backstage, their weapons in their holsters. After intervening in one of the early fights between the Hells Angels and fans, they took note of how thoroughly outnumbered they were, and thereafter ceded the field to the Angels. Few fans or performers saw them for the remainder of the day.

The counterculture saw the Hells Angels as they wanted to see them, turning a blind eye to their professed love of violence, their misbegotten politics, and their outright racism. That alliance was in the process of breaking down this Saturday, shattered by the overly ambitious professional demands imposed on the Angels, and a creeping rage toward the music-loving masses.

The bikers’ ferociousness, and their remarkable sense of cohesion, made for a notable contrast with the idealism of the crowd they patrolled. The counterculture believed itself to be an organized mass, intent on fomenting change in the United States: ending a war, returning power to the people. But seeing the Hells Angels was a reminder of the counterculture’s limitations, embodied in the actions of their foes.

The Angels were violent authoritarians in the guise of bikers, intent on imposing their will on an unruly crowd. They were also a cohesive unit, acting in unison. The Angels had determined who would run Altamont, and what was and was not permissible there, and no one would be permitted to question the new order. This was the day’s new reality. The counterculture spoke of unity, but the Hells Angels lived it. It was so powerful in action that it could hold hundreds of thousands in its thrall. What good was a peace sign against someone wielding a pool cue?

Some of the Angels approached Sam Cutler, guiding the action onstage, looking for guidance about how to handle unruly crowd members. This rushed tête-à-tête only further underscored the differences between Altamont and previous concerts, in which the Angels had putatively provided security but rarely interacted with the crowd. “We don’t give a fuck,” Cutler bluntly told the Angels. “Just keep these people away.” Whether or not the Stones and their representatives knew what they were doing in hiring the Hells Angels, they had now given them explicit authority to manhandle the crowd. Passive negligence regarding the show’s security had now become, due to the disinterest of the Rolling Stones and their handlers, an active policy of violence and domination. The Angels were now patrolling deeper into the crowd, targeting the 18-wheelers that had been parked next to the stage. The Angels seized fans sitting atop the trucks and flung them off, a dozen or more feet down to the hard ground.

To continue reading how the Hells Angels were involved in the tragedy at Altamont, pick up Just A Shot Away by Saul Austerlitz.

SAUL AUSTERLITZ has had work published in the LA Times, NY Times, Boston Globe, Slate, the Village Voice, The New Republic, the SF Chronicle, Spin, Rolling Stone, and Paste. He is the author of several previous books, including Money for Nothing: A History of the Music Video from the Beatles to the White Stripes. He lives in Brooklyn.

The post The Hells Angels’ Role at Altamont appeared first on The History Reader.

Probably one of the most surprising revelations of the full mapping of the human genome, in 2003, was that the human body is filled with shards of ancient retroviruses. In fact, about 8 to 9% of our DNA is composed of viral fragments, which, millions of years ago, began to infect our DNA. How did that happen? Retroviruses are special. They store information in a single-stranded molecule of RNA, and when they infect a cell, they release an enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, that allows the virus to hijack our cellular machinery to copy and paste itself into the DNA of our cells. That’s how a retrovirus begins the process of making billions of copies of itself, which makes us sick.

Probably one of the most surprising revelations of the full mapping of the human genome, in 2003, was that the human body is filled with shards of ancient retroviruses. In fact, about 8 to 9% of our DNA is composed of viral fragments, which, millions of years ago, began to infect our DNA. How did that happen? Retroviruses are special. They store information in a single-stranded molecule of RNA, and when they infect a cell, they release an enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, that allows the virus to hijack our cellular machinery to copy and paste itself into the DNA of our cells. That’s how a retrovirus begins the process of making billions of copies of itself, which makes us sick.

They talked about the need for peace between religions as well as nations, Rubens later recalling the duke as showing a ‘laudable zeal’ for the ‘interests of Christianity’. Rubens had heard the military threats that had accompanied James’s final weeks, and expressed the hope that, now Charles was securely installed on the throne, his father’s more peaceful approach to diplomacy might be revived, focused on preventing rather than stirring up war, the ‘scourge from Heaven’.

They talked about the need for peace between religions as well as nations, Rubens later recalling the duke as showing a ‘laudable zeal’ for the ‘interests of Christianity’. Rubens had heard the military threats that had accompanied James’s final weeks, and expressed the hope that, now Charles was securely installed on the throne, his father’s more peaceful approach to diplomacy might be revived, focused on preventing rather than stirring up war, the ‘scourge from Heaven’. On this day, there were approximately twenty or twenty-five Hells Angels present, with another few dozen prospects and hangers-on with them. The prospects, in particular, knew that the best way to win the Angels’ acceptance was with a demonstration of their unyielding toughness. With little police presence at Altamont, and almost no security presence besides the Hells Angels, bikers had carte blanche to strong-arm the audience. And as fans kept pushing forward from the back, those up front would get dangerously close to the Hells Angels and their motorcycles.

On this day, there were approximately twenty or twenty-five Hells Angels present, with another few dozen prospects and hangers-on with them. The prospects, in particular, knew that the best way to win the Angels’ acceptance was with a demonstration of their unyielding toughness. With little police presence at Altamont, and almost no security presence besides the Hells Angels, bikers had carte blanche to strong-arm the audience. And as fans kept pushing forward from the back, those up front would get dangerously close to the Hells Angels and their motorcycles. Five-foot-seven and 175 pounds, all muscle from his day job as a roofer, “Hawkeye” came with three knives and a .22 revolver, in the mood to party and only too glad to hassle anyone who got in the way of his fun. Hawkeye and his friends from another motorcycle group, the Sons of Hawaii, had come with a fistful of counterfeit $20 bills they had printed at a local copy shop, planning to use them to buy drugs from sellers in the crowd. Upon arrival at Altamont, they realized there would be no need for such elaborate chicanery. He and his friends would steal money and drugs from those displaying their stashes or their bankrolls, and then violently manhandle them when they complained. The victims would almost inevitably head off to find their friends, and when they came back, spoiling for a fight, Hawkeye and his friends would beat them once more. The victims were scared, and desperate for a security presence to resolve the situation, but no authority was higher than that of the Hells Angels. Hawkeye didn’t worry about their complaints, or even their fitful attempts to get rough. Unless they came back with an army, they would have no chance at all. He and his friends were pushing people around, kicking ass, and stealing girlfriends, and having the time of their lives doing it.

Five-foot-seven and 175 pounds, all muscle from his day job as a roofer, “Hawkeye” came with three knives and a .22 revolver, in the mood to party and only too glad to hassle anyone who got in the way of his fun. Hawkeye and his friends from another motorcycle group, the Sons of Hawaii, had come with a fistful of counterfeit $20 bills they had printed at a local copy shop, planning to use them to buy drugs from sellers in the crowd. Upon arrival at Altamont, they realized there would be no need for such elaborate chicanery. He and his friends would steal money and drugs from those displaying their stashes or their bankrolls, and then violently manhandle them when they complained. The victims would almost inevitably head off to find their friends, and when they came back, spoiling for a fight, Hawkeye and his friends would beat them once more. The victims were scared, and desperate for a security presence to resolve the situation, but no authority was higher than that of the Hells Angels. Hawkeye didn’t worry about their complaints, or even their fitful attempts to get rough. Unless they came back with an army, they would have no chance at all. He and his friends were pushing people around, kicking ass, and stealing girlfriends, and having the time of their lives doing it.