Anastasis. Research in Medieval Culture and Art is an international peer-reviewed journal edited by The Research Center of Medieval Art, ”Vasile Drăguț” at the “George Enescu” National University of Arts of Iași, România.

Anastasis. Research in Medieval Culture and Art is an open access journal, which publish original articles in the areas of medieval art and medieval culture. The aim is to stir people’s interest for scientific research regarding the Middle Ages in order to qualify the modern preoccupation with medieval art.

Anastasis. Research in Medieval Culture and Art is an open access journal, which publish original articles in the areas of medieval art and medieval culture. The aim is to stir people’s interest for scientific research regarding the Middle Ages in order to qualify the modern preoccupation with medieval art.

In order to offer a more complex and nuanced set of ideas, the journal has an interdisciplinary character and publishes research about visual arts, restoration, architecture, music, theatre, theology, philosophy, literature, sciences etc.

Each issue contains research articles on varied topics, as well as sections on Medieval Art and Civilisation and Medieval Culture in Contemporary Research. Finally, there is a section with book reviews. Judging from the table of contents, the journal offers a fine and varied glimpse into a lively research center somewhat on the periphery of the mainstream (Anglo-American) milieu of medieval art research.

The first issue for 2018 has just been published. Call for papers for issue two ends 15.09.2018

Table of contents

Constantin Ciobanu

Les inscriptions simulées de la peinture médiévale roumaine dans le contexte de l’art et de la pensée orthodoxes / Simulated Inscriptions of Romanian Medieval Painting in the Context of Orthodox Art and Thinking

Article PDF

Florin Crîșmăreanu

Théologie de la beauté dans les écrits de Maxime le Confesseur / The Theology of Beauty in the Writings of Maximus the Confessor

Article PDF

Brînduşa Grigoriu

Yseut et Tristan comme parents : le Roman d’Ysaÿe le Triste / Yseut and Tristan as Parents : the Romance of Ysaÿe le Triste

Article PDF

Irina-Andreea Stoleriu

Adrian Stoleriu

Representations of the Pope in Western Art

Article PDF

Bogdan Ungurean

Notes on the St. Theodore’s church iconostasis from Iași. Technique of execution, stylistically description and state of conservation

Article PDF

Oana Maria Nicuţă

Visual Litteracy and the Crux of the Visible: Is Stained Glass a Manifestation of the Diaphanous?

Article PDF

Cristina Gelan

Ideology, Symbolism and Representation through Byzantine Art

Article PDF

Angela Simalcsik

New Cases of Symbolic Trepanation from the Medieval Period Discovered in the Space between Prut and Dniester

Article PDF

MEDIEVAL CULTURE IN CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH

Ioana Palamar

Self-Portrait: Between Normality and Psychosis

Article PDF

Codrina-Laura Ioniţă

“Le Buisson Ardent de la Vierge”. Une lettre et une icône / The Burning Bush of Virgin Mary. A letter and an icon

Article PDF

Luana Stan

Teodora-Sânziana Stan

Revalorisation des rituels ancestraux des amérindiens du Canada dans la musique de Murray Schaffer / Revalorization of Canadian Amerindian Rituals in Murray Schafer’s Music

Article PDF

Paula Onofrei

Medieval Symbols in “The Name of the Rose”, by Umberto Eco

Article PDF

Rosângela Aparecida da Conceição

Thomaz Scheuchl, the Trajectory of a Disciple of Beuron: from the Restoration of the Cathedral of the Ascension in Satu Mare to the Paintings of Churches in Brazil

Article PDF

The post Anastasis – Journal About Research in Medieval Culture and Art appeared first on Medieval Histories.

Powered by WPeMatico

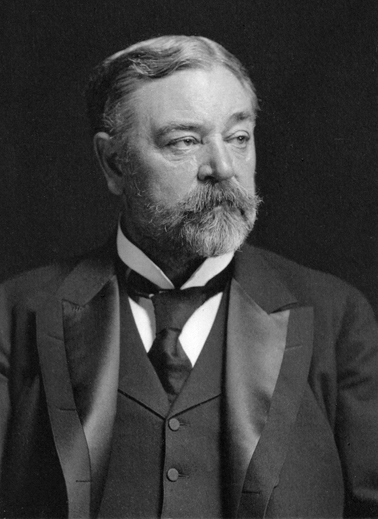

Robert attended the finest schools, such as Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard College, and Harvard Law School. By age twenty-one, he’d already attended both of his father’s presidential inaugurations. A year later, he left Harvard Law School to become the assistant adjutant to General Grant, a mere two months before the

Robert attended the finest schools, such as Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard College, and Harvard Law School. By age twenty-one, he’d already attended both of his father’s presidential inaugurations. A year later, he left Harvard Law School to become the assistant adjutant to General Grant, a mere two months before the  Yet sadness also followed Robert. He’d

Yet sadness also followed Robert. He’d  Robert made his last public appearance at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. in May 1922. He died at Hildene four years later, one week shy of his eighty-third birthday. Though he desired to be buried in the Lincoln Tomb in Springfield, Illinois, his wife interred him in a grand sarcophagus at Arlington Cemetery.

Robert made his last public appearance at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. in May 1922. He died at Hildene four years later, one week shy of his eighty-third birthday. Though he desired to be buried in the Lincoln Tomb in Springfield, Illinois, his wife interred him in a grand sarcophagus at Arlington Cemetery.