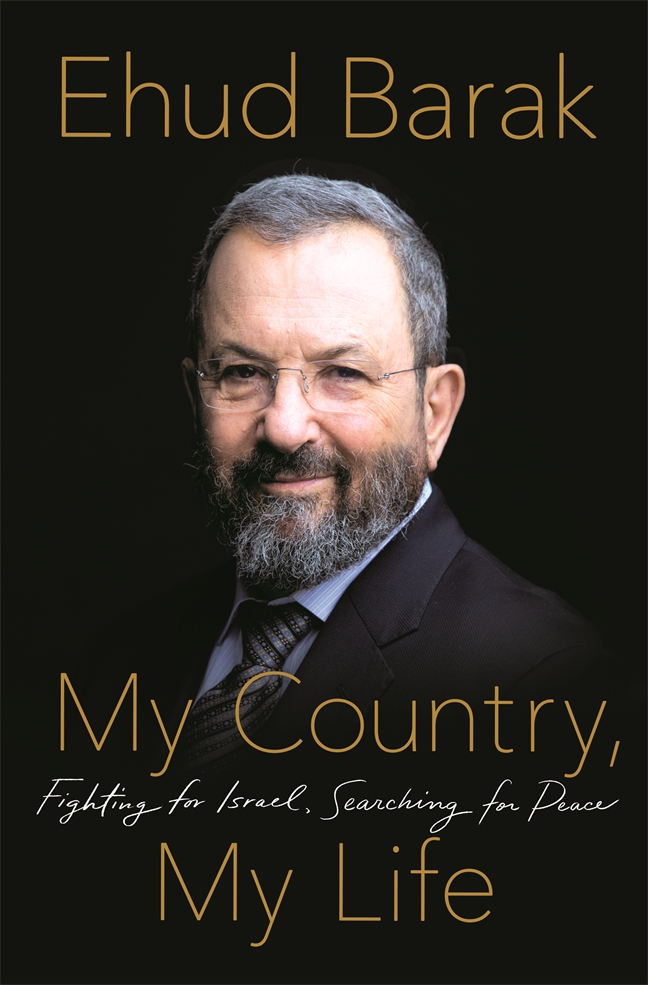

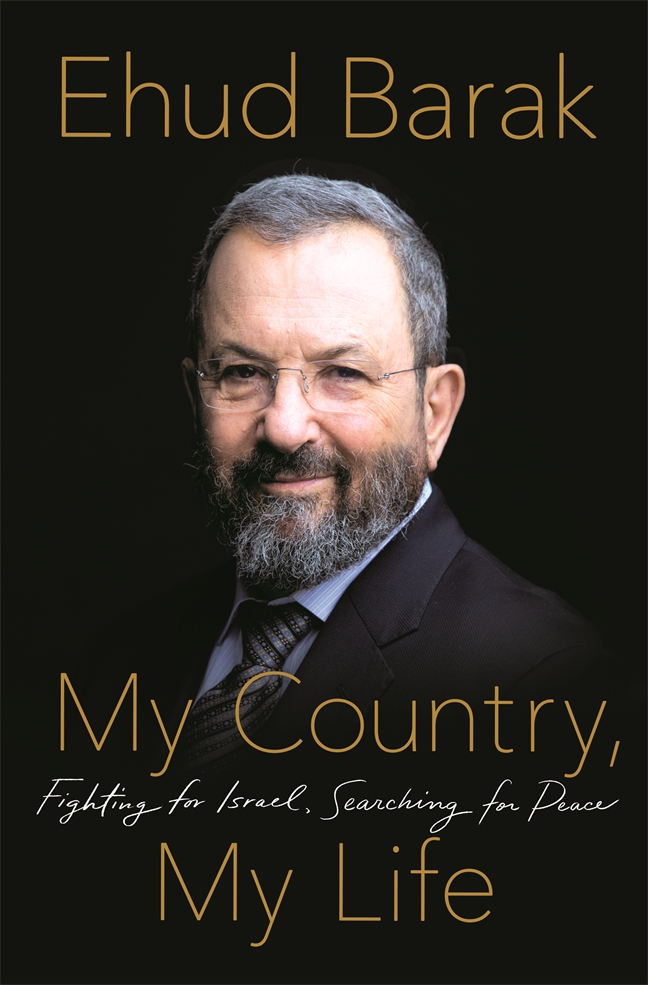

by Ehud Barak

In the summer of 2000, the most decorated soldier in Israel’s history—Ehud Barak—set himself a challenge as daunting as any he had faced on the battlefield: to secure a final peace with the Palestinians. He would propose two states for two peoples, with a shared capital in Jerusalem. He knew the risks of failure. But he also knew the risks of not trying: letting slip perhaps the last chance for a generation to secure genuine peace.

It was a moment of truth.

It was one of many in a life intertwined, from the start, with that of Israel. Born on a kibbutz, Barak became commander of Israel’s elite special forces, then army Chief of Staff, and ultimately, Prime Minister.

My Country, My Life tells the unvarnished story of his—and his country’s—first seven decades; of its major successes, but also its setbacks and misjudgments. He offers candid assessments of his fellow Israeli politicians, of the American administrations with which he worked, and of himself. Drawing on his experiences as a military and political leader, he sounds a powerful warning: Israel is at a crossroads, threatened by events beyond its borders and by divisions within. The two-state solution is more urgent than ever, not just for the Palestinians, but for the existential interests of Israel itself. Only by rediscovering the twin pillars on which it was built—military strength and moral purpose—can Israel thrive. Keep reading for an excerpt of Ehud Barak’s definitive memoir.

My Country, My Life tells the unvarnished story of his—and his country’s—first seven decades; of its major successes, but also its setbacks and misjudgments. He offers candid assessments of his fellow Israeli politicians, of the American administrations with which he worked, and of himself. Drawing on his experiences as a military and political leader, he sounds a powerful warning: Israel is at a crossroads, threatened by events beyond its borders and by divisions within. The two-state solution is more urgent than ever, not just for the Palestinians, but for the existential interests of Israel itself. Only by rediscovering the twin pillars on which it was built—military strength and moral purpose—can Israel thrive. Keep reading for an excerpt of Ehud Barak’s definitive memoir.

Kibbutz Roots

I am an Israeli. But I was born in British-ruled Palestine, on a fledgling kibbutz: a cluster of wood-and-tar-paper huts amid a few orange groves and vegetable fields and chicken coops. It was just across the road from an Arab village named Wadi Khawaret, whose residents fled in the weeks before the establishment of the State of Israel, when I was six years old.

As prime minister half a century later, during my stubborn yet ultimately fruitless drive to secure a final peace treaty with Yasir Arafat, there were media suggestions that my childhood years gave me a personal understanding of the pasts of both our peoples, Jews and Arabs, in the land that each saw as its own. But that is in some ways misleading. Yes, I did know firsthand that we were not alone in our ancestral homeland. At no point in my childhood was I ever taught to hate the Arabs. I never did hate them, even when, in my years defending the security of Israel, I had to fight, and defeat, them. But my conviction that they, too, needed the opportunity to establish a state came only later, after my many years in uniform—especially when, as deputy chief of staff under Yitzhak Rabin, Israel faced a violent uprising in the West Bank and Gaza that became the first intifada. And while my determination as prime minister to find a negotiated resolution to our conflict was in part based on a recognition of the Palestinian Arabs’ national aspirations, the main impulse was my belief that such a compromise was profoundly in the interest of Israel, whose existence I had spent decades defending on the battlefield and which I was ultimately elected to lead.

Zionism, the political platform for the establishment of a Jewish state, emerged in the late 1800s in response to a brutal reality. That, too, was a part of my own family’s story. Most of the world’s Jews, who lived in the Russian empire and Poland, were trapped in a vise of poverty, powerlessness, and anti-Semitic violence. Even in the democracies of Western Europe, Jews were not necessarily secure. Theodor Herzl, a largely assimilated Jew in Vienna, published the foundational text of Zionism in 1896. It was called Der Judenstaat. “Jews have sincerely tried everywhere to merge with the national communities in which we live, seeking only to preserve the faith of our fathers,” he wrote. “In vain are we loyal patriots, sometimes super-loyal. In vain do we make the same sacrifices of life and property as our fellow citizens … In our native lands where we have lived for centuries, we are still decried as aliens.” Zionism’s answer was the establishment of a state of our own, in which we could achieve the self-determination and security denied to us elsewhere.

During the 1890s and the early years of the new century, more than a million Jews fled Eastern Europe, but mostly for America. It was only in the 1920s and 1930s that significant numbers arrived in Palestine. Then, within a few years, Hitler rose to power in Germany. The Jews of Europe faced not just discrimination and pogroms. They were systematically, industrially murdered. From 1939 until early 1942, when I was born, nearly 2 million Jews were killed. Six million would die by the end of the war. Almost the whole world, including the United States, rejected pleas to provide a haven for those who might have been saved. Even after Hitler was defeated, the British shut the doors of Palestine to those who had somehow survived.

* * *

I was three when the Holocaust ended. Three years later Israel was established, in May 1948, and neighboring Arab states sent in their armies to try to snuff the state out in its infancy. It would be some years before I fully realized that this first Arab-Israeli war was the start of an essential tension in my country’s life, and my own: between the Jewish ethical ideals at the core of Zionism and the reality of our having to fight, and sometimes even kill, in order to secure, establish, and safeguard our state. Yet even as a small child, I was keenly aware of the historic events swirling around me.

Mishmar Hasharon, the hamlet north of Tel Aviv where I spent the first seventeen years of my life, was one of the early kibbutzim. These collective farming settlements had their roots in Herzl’s view that an avant-garde of “pioneers” would need to settle a homeland that was still economically undeveloped, and where even farming was difficult. Members of Jewish youth groups from Eastern Europe, among them my mother, provided most of the pioneers, drawing inspiration not just from Zionism but from the still untainted collectivist ideals represented by the triumph of Communism over the czars in Russia.

It is hard for people who didn’t live through that time to understand the mind-set of the kibbutzniks. They had higher aspirations than simply planting the seeds of a future state. They wanted to be part of transforming what it meant to be a Jew. The act of first taming, and then farming, the soil of Palestine was not just an economic imperative. It was seen as deeply symbolic of Jews finally taking control of their own destiny. It was a message that took on an even greater power and poignancy after the mass murder of the Jews of Europe during the Holocaust.

Even for many Israelis nowadays, the physical challenges and the all-consuming collectivism of life on an early kibbutz are hard to imagine. Among the few dozen families in Mishmar Hasharon when I was born, there was no private property. Everything was communally owned and allocated. Every penny—or Israeli pound—earned from what we produced went into a communal kitty, from which each one of the seventy-or-so families got a small weekly allowance. By “small,” I mean tiny. For my parents and others, even the idea of an ice cream cone for their children was a matter of keen financial planning. More often, they would save each weekly pittance with the aim of pooling them at birthday time, when they might stretch to the price of a picture book, or a small toy.

Decisions on any issue of importance were taken at the aseifa, the weekly meeting of kibbutz members held on Saturday nights in our dining hall. The agenda would be tacked up on the wall the day before, and the session usually focused on one issue, ranging from major items like the kibbutz’s finances to whether, for instance, our small platoon of delivery drivers should be given pocket money to buy a sandwich or a coffee on their days outside the kibbutz or be limited to wrapping up bits of the modest fare on offer at breakfast time. That debate ended in a classic compromise: a little money, very little, so as to avoid violating the egalitarian ethos of the kibbutz.

But perhaps the aspect of life on the kibbutz most difficult for outsiders to understand, especially nowadays, is that we children were raised collectively. We lived in dormitories, organized by age group and overseen by a caregiver: in Hebrew, a metapelet, usually a woman in her twenties or thirties. For a few hours each afternoon and on the Jewish Sabbath, we were with our parents. Otherwise, we lived and learned in a world consisting almost entirely of other children.

Everything around us was geared toward making us feel like a band of brothers and sisters, as part of the wider collective. Until our teenage years, we weren’t even graded in school. And though we didn’t actually study how to till the land, some of my fondest early memories are of our “children’s farm”—the vegetables we grew, the goats we milked, the hens and chickens that gave us our first experience of how life was created. And the aroma always wafting from the stone ovens in the bakery at the heart of the kibbutz, where we could see the bare-chested young men producing loaf after loaf of bread, not just for Mishmar Hasharon but small towns and villages for miles around.

Until our teenage years, we lived in narrow, oblong homes, four of us to a room, unfurnished except for our beds, under which we placed our pair of shoes or sandals. At one end of the corridor was a set of shelves where we collected a clean set of underwear, pants, and socks each week. At the other end were the toilets—at that point, the only indoor toilets on the kibbutz, with real toilet seats rather than just holes in the ground. All of us showered together until the age of twelve. I can’t think of a single one of us who went on to marry someone from our own age group in the kibbutz—it would have seemed almost incestuous.

Mishmar Hasharon and other kibbutzim have long since abandoned the practice of collective child rearing. Some in my generation look back on the way we were raised not only with regret, but pain: a sense of parental absence, abandonment, or neglect. My own memories are more positive. The irony is that we probably spent more waking time with our parents than town or city children whose mothers and fathers worked nine-to-five jobs. The difference came at bedtime, or during the night. If you woke up unsettled, or ill, the only immediate prospect of comfort was from the metapelet or another of the kibbutz grown-ups who might be on overnight duty. Still, my childhood memories are overwhelmingly of feeling happy, safe, protected. I do remember waking up once, late on a stormy winter night when I was nine, in the grips of a terrible fever. I’d begun to hallucinate. I got to my feet and, without the thought of looking anywhere else for help, made my wobbly way through the rain to my parents’ room and fell into their bed. They hugged me. They dabbed my forehead with water. The next morning, my father wrapped me in a blanket and took me back to the children’s home.

To the extent that I was aware my childhood was different, I was given to understand it was special, that we were the beating heart of a Jewish state about to be born. I once asked my mother why other children got to live in their own apartments in places like Tel Aviv. “They are ironim,” she said. City-dwellers. Her tone made it clear they were to be viewed as a slightly lesser species.

EHUD BARAK served as Israel’s Prime Minister from 1999 to 2001. He was the leader of the Labor Party from 2007 until 2011, and Minister of Defense, first in Olmert’s and then in Netanyahu’s government from 2007 to 2013. Before entering politics, he was a key member of the Israeli military, occupying the position of Chief-of-Staff. Barak holds a B.Sc. in Physics and Math from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and an M.Sc. degree from Stanford in Engineering-Economic Systems.

The post Fighting for Israel, Searching for Peace appeared first on The History Reader.

My Country, My Life tells the unvarnished story of his—and his country’s—first seven decades; of its major successes, but also its setbacks and misjudgments. He offers candid assessments of his fellow Israeli politicians, of the American administrations with which he worked, and of himself. Drawing on his experiences as a military and political leader, he sounds a powerful warning: Israel is at a crossroads, threatened by events beyond its borders and by divisions within. The two-state solution is more urgent than ever, not just for the Palestinians, but for the existential interests of Israel itself. Only by rediscovering the twin pillars on which it was built—military strength and moral purpose—can Israel thrive. Keep reading for an excerpt of Ehud Barak’s definitive memoir.

My Country, My Life tells the unvarnished story of his—and his country’s—first seven decades; of its major successes, but also its setbacks and misjudgments. He offers candid assessments of his fellow Israeli politicians, of the American administrations with which he worked, and of himself. Drawing on his experiences as a military and political leader, he sounds a powerful warning: Israel is at a crossroads, threatened by events beyond its borders and by divisions within. The two-state solution is more urgent than ever, not just for the Palestinians, but for the existential interests of Israel itself. Only by rediscovering the twin pillars on which it was built—military strength and moral purpose—can Israel thrive. Keep reading for an excerpt of Ehud Barak’s definitive memoir.