Head reliquary of St Eustace c. 1180 -1200 belongs to the category of “Speaking Reliquaries”, which informs us of their content.

In the 19thcentury the treasures preserved in the Cathedral in Basle went on the market. One of the outstanding pieces was the reliquary of St. Eustace from the 12thcentury. Such head reliquaries, also known as `chefs’, were popular in the medieval period. They belong to the category of so-called “speaking” reliquaries, which through their form indicate their content. In 1850, the reliquary was acquired by the British Museum.

The head itself is made of silver-gilt repoussé metal sheets with a gem-set filigree circlet binding the straight hair. The head measures (H) 35 cm x (W)16,6 cm x (D)18,4 cm and weighs 1,6 kg. The head is supported by a fully carved core made of sycamore wood. Also in the shape of a head, the top forms a lid covering a hollow compartment for relics. The existence of the inner wooden head was not discovered until 1956, when the silver case was being cleaned. The relic compartment was then opened, and a number of fragments of bone wrapped in cloth and identified by vellum (relic tituli) were found, which hitherto had clearly not been disturbed. Some of these relics were supposedly fragments of the skull of Saint Eustace, a Roman military saint. The relics were returned to Basle, but the vellum `tituli’, cloth fragments and cotton wadding were retained by the British Museum.

It is thought that the wooden head was the original reliquary, which was then covered in silver-gilt sheets and fitted with the diadem.

The gem-set filigree circlet is especially valuable. Such circlets might be gifts from wealthy nobles. And may perhaps have been worn in a secular context before being donated. This diadem is made of filigree adorned with a series of gems recycles from the Roman past. Nine gems are composed of varieties of quartz (rock crystal, chalcedony, amethyst, carnelian), two of aragonite (pearl, mother of pearl), one of obsidian and six of glass. This use of Roman materials reveals the value placed on the classical past by medieval goldsmiths and their patrons.

Around the plinth are gold plaques in the form of the twelve apostles standing under an arcade of trefoil-headed arches. This will also have been decorated with recycles ems and glass fragments, but only two remain.

St Eustace

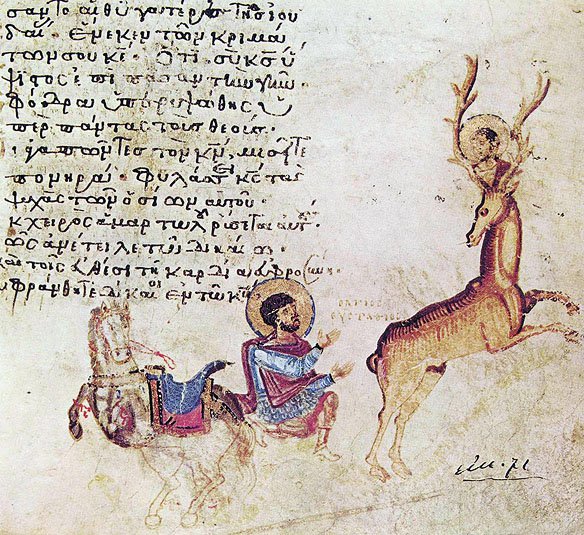

St. Eustace was a Roman soldier and Christian martyr. Before his conversion, legend has it he was a Roman general serving under Trajan and known under the name of Placidus. While hunting a stag near Tivoli, he saw a crucifix lodged in between the antlers of the stag. This led to the conversion of his whole family as well as the change of his name to Eustatius (from Greek, Eustachios, meaning fruitful, well standing, steadfast). His vita is preserved in the form of a highly romantic legend presenting him as a Job-figure, until his martyrdom in AD 118, when he was supposedly roasted to death with his family inside a bronze statue of an ox.

According to Pope Gregory II (731 – 41), an early church was dedicated to him in Rome. Veneration, though, is mainly dated to the 12thcentury. One of the earlier presentations, though may be found on the Harbaville Triptych from Byzantium, now in Louvre, showing a panoply of Roman soldiers turned martyrs – St Theodore the Recruit, St Theodore the General, St George, and St Eustace. Later, we find his relics at an altar in the royal basilica of St. Denis as well as depicted on a Romanesque capital at the Abbey in Vézeley. The saint may also be found in psalters illustrating Psalm 96, 2 – 12. St. Eustace obviously belonged to the group of martyrs celebrated for their conversion from Roman Soldier to Miles Christi.

SEE MORE

St. Eustace Head reliquary c.1180-1200, Basle, Switzerland (British Museum)

READ MORE:

Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe

By Martina Bagnoli, Holger Klein, C. Griffith Mann, and James Robinson.

London, British Museum Press, 2011

Matter of Faith: An Interdisciplinary Study of Relics and Relic Veneration in the Medieval Period

Edited by James Robinson, Lloyd de Beer and Anna Harnden

The British Museum Press 2018

The post The St Eustace Head Reliquary appeared first on Medieval Histories.

Powered by WPeMatico