by Peter Laufer

The clash of old and new in Yunnan Province, China, is mind-numbing. Ancient Buddhist temples vie for attention with massive infrastructure projects around the provincial capital, Kunming: parades of towering apartment blocks, superhighways and bullet trains. One ancient that seemed gone without a trace was the gentle Yunnan box turtle, Cuora yunnanensis. Hunted—as are turtles and tortoises worldwide—for pets, food and medicine, the shy animal disappeared.

Turtle researchers thought they saw the last Yunnan box turtle in 1940. When it died turtle aficionados worldwide mourned the loss and the species was officially listed as extinct. Extinct: it’s a sobering word for natural historians. Threatened and endangered animals stand a chance of recovering, of re-establishing a viable population. But extinct is forever. Gone from the Earth. And one more lost link closing in toward our own human extinction. Because biodiversity equals survival.

Over sixty-five years later, in 2006, a mysterious turtle showed up in the animal section of Kunming’s sprawling Jingxing market, its handler asking passersby and shopkeepers if they knew its identity. No turtle purveyors could help, but a snapshot was uploaded to the internet and the crowdsourcing worked. Excited researchers, breeders, and turtle lovers learned that the species they thought was lost forever had in fact survived. Yet where other individuals may be located was unknown. A year later a second was found in an older man’s Yunnan home. (He could have had it since he was a child; both the turtle and its keeper were youngsters back when the species thrived.)

The Kunming Institute of Zoology now is home to at least some of the few Yunnan box turtles known to exist. Scientists there are hard at work taking advantage of the unexpected resurfacing of the native species as they try to prevent reporting a second extinction. Herpetologist Rao Dingqi had already been searching the wilds of Yunnan when news reached him of the specimen for sale at the Jingxing market and the other one at the house where it was kept as a good luck pet. Soon after that news, Rao found three more himself and then after a few more years of prowling what’s left of the Yunnan wilds, another three more. Exactly where he discovered the rare turtles he kept a close-guarded secret; he was competing with poachers. Because of its rarity and the lust of collectors, Cuora yunnanensis may be the priciest turtle on the global black market.

The Kunming Institute of Zoology now is home to at least some of the few Yunnan box turtles known to exist. Scientists there are hard at work taking advantage of the unexpected resurfacing of the native species as they try to prevent reporting a second extinction. Herpetologist Rao Dingqi had already been searching the wilds of Yunnan when news reached him of the specimen for sale at the Jingxing market and the other one at the house where it was kept as a good luck pet. Soon after that news, Rao found three more himself and then after a few more years of prowling what’s left of the Yunnan wilds, another three more. Exactly where he discovered the rare turtles he kept a close-guarded secret; he was competing with poachers. Because of its rarity and the lust of collectors, Cuora yunnanensis may be the priciest turtle on the global black market.

Herpetologist Rao Dingqi in his lab.

At last count Herpetologist Rao and his colleagues have collected ten wild-caught Yunnan box turtles, turtles they keep in an assurance colony at the Institute. There they’ve managed to double the colony size by successfully breeding the wild turtles. The Kunming Institute of Biology is seeking financial aid from the Chinese government and from the private sector to support its ongoing research of the rare box turtle and for its development of a viable captive-bred colony. Institute scientists also seek help cordoning off and policing the areas where Rao discovered the wild animals.

Meanwhile, Rao keeps looking for more, as do competing scientists from Europe and North America. Of course, they are not alone: with the high price tag as an indication of potential compensation for illicit trafficking of Yunnan box turtles, poachers are motivated to be out in force around the province seeking one of the rarest turtle species in the world – not for science but for profit.

Meanwhile, Rao keeps looking for more, as do competing scientists from Europe and North America. Of course, they are not alone: with the high price tag as an indication of potential compensation for illicit trafficking of Yunnan box turtles, poachers are motivated to be out in force around the province seeking one of the rarest turtle species in the world – not for science but for profit.

What does this cousin of common box turtles look like? Unlike the colorful turtle and tortoise species that can be found elsewhere in Asia, like the spectacular Burmese star, Yunnan box turtles show off a rather drab brown coloring on their high-domed carapaces. The plastron adds some yellow to its costume. Head to tail it’s a little smaller than a football. Nonetheless, according to even scientist Rao, it’s a powerful animal. As is the case with other turtles and tortoises, touching one, according to Chinese tradition, brings good fortune.

That role of good luck charm adds to the underground value of the Yunnan box turtle and all other Chelonians. About the turtle and tortoise resale economy, the president of the Turtle Conservancy, Eric Goode, says, “Turtles are on steroids!”

Turtle at the Pan Long Temple.

Just how much does Cuora yunnanensis command in the black marketplace? Rao Dingqi has seen them advertised in China for $15,000. But back in the States the number quoted is over ten times higher with at least one asking price for a healthy adult Yunnan box turtle a hard-to-fathom $200,000.

The bullet train ride across China from Kunming to Hong Kong is fast, less than eight hours. But before boarding and after the trip back in time with Yunnan box turtles, a stop at the Pan Long Temple to visit the Smiling Buddha offers perspective. The Buddha is displayed behind glass, smiling as a guide offers a goodbye message. “Forget troubles,” he says. “Everything is happy. Everything is okay. You don’t have to worry because he has a belly and you can put everything in it.”

Comforting words of farewell.

Journalist Peter Laufer is the James Wallace Chair Professor in Journalism at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication. He is the author of Dreaming in Turtle: A Journey Through the Passion, Profit, and Peril of Our Most Coveted Prehistoric Creatures and Organic: A Journalist’s Quest to Discover the Truth Behind Food Labeling.

The post Recovering History’s Most Expensive Turtle appeared first on The History Reader.

Powered by WPeMatico

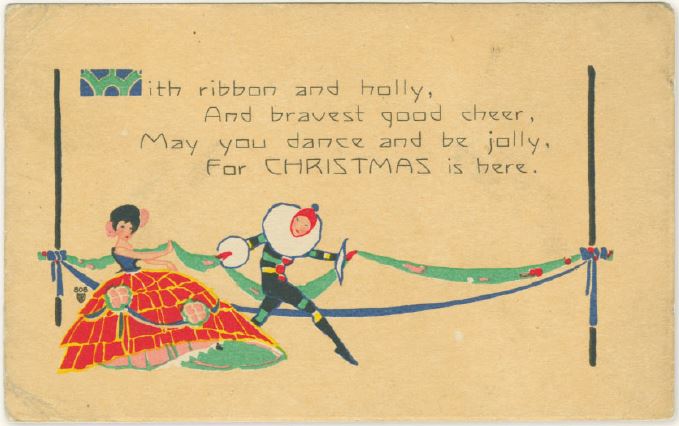

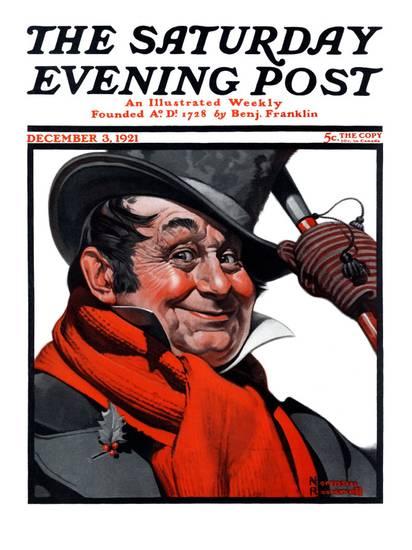

Judith Waggoner writes that “After the shock of World War I, people craved the comfort of more innocent times. They found it in the world of Charles Dickens. There were four different film versions of A Christmas Carol to choose from, and magazine covers of the era often depicted scenes with the flavor of merry old England.” The “old English” sort of Christmas, by the way, never really existed in America; U.S. Puritan heritage has been decidedly opposed to Christmas merrymaking. Thus, the pseudo-Dickensian yuletide of the 1920s amounted to pure nostalgic fantasy. This nostalgia translated into decorations with carriage lantern and antique candle holder motifs, and Victorian-style paper silhouettes, while English holly, rather than today’s pine boughs, were the favored holiday greenery. (In fact, in my home region of Western Washington State, holly planted in the 1920s as a holiday cash crop is now considered an out-of-control invasive species.) In keeping with that pseudo-Dickensian theme, Norman Rockwell’s cover for The Saturday Evening Post’s December 3, 1921 issue depicts a ruddy-cheeked coachman in a Victorian top hat and collar, with holly on his lapel. Similarly, Rockwell’s December 8, 1928 cover shows a man and woman in mid-nineteenth-century attire dancing beneath the mistletoe. They, too, are ruddy-cheeked. Must be something in the punch.

Judith Waggoner writes that “After the shock of World War I, people craved the comfort of more innocent times. They found it in the world of Charles Dickens. There were four different film versions of A Christmas Carol to choose from, and magazine covers of the era often depicted scenes with the flavor of merry old England.” The “old English” sort of Christmas, by the way, never really existed in America; U.S. Puritan heritage has been decidedly opposed to Christmas merrymaking. Thus, the pseudo-Dickensian yuletide of the 1920s amounted to pure nostalgic fantasy. This nostalgia translated into decorations with carriage lantern and antique candle holder motifs, and Victorian-style paper silhouettes, while English holly, rather than today’s pine boughs, were the favored holiday greenery. (In fact, in my home region of Western Washington State, holly planted in the 1920s as a holiday cash crop is now considered an out-of-control invasive species.) In keeping with that pseudo-Dickensian theme, Norman Rockwell’s cover for The Saturday Evening Post’s December 3, 1921 issue depicts a ruddy-cheeked coachman in a Victorian top hat and collar, with holly on his lapel. Similarly, Rockwell’s December 8, 1928 cover shows a man and woman in mid-nineteenth-century attire dancing beneath the mistletoe. They, too, are ruddy-cheeked. Must be something in the punch. Christmas Dinner: No.1: Oyster Cocktails in Green Pepper Shells, Celery, Ripe Olives, Roast Goose with Potato Stuffing, Apple Sauce, String Beans, Potato Puff, Lettuce Salad with Riced Cheese and Bar-le-Duc French Dressing, Toasted Wafers, English Plum Pudding, Bonbons, Coffee. No.2: Cream of Celery Soup, Bread Sticks, Salted Peanuts, Stuffed Olives, Roast Beef, Yorkshire Pudding, Potato Soufflé, Spinach in Eggs, White Grape Salad with Guava Jelly, French Dressing, Toasted Crackers, Plum Pudding, Hard Sauce, Bonbons, Coffee.

Christmas Dinner: No.1: Oyster Cocktails in Green Pepper Shells, Celery, Ripe Olives, Roast Goose with Potato Stuffing, Apple Sauce, String Beans, Potato Puff, Lettuce Salad with Riced Cheese and Bar-le-Duc French Dressing, Toasted Wafers, English Plum Pudding, Bonbons, Coffee. No.2: Cream of Celery Soup, Bread Sticks, Salted Peanuts, Stuffed Olives, Roast Beef, Yorkshire Pudding, Potato Soufflé, Spinach in Eggs, White Grape Salad with Guava Jelly, French Dressing, Toasted Crackers, Plum Pudding, Hard Sauce, Bonbons, Coffee. Alva decided to attend a meeting of the Society for the Betterment of Working Children, which Armide had joined not long before. The group met once each month at the home of its president. Miss Annalisa Beekman was a young Knickerbocker lady whose pale eyes and pale hair and pale skin made her vulnerable to disappearance if she stood too near draperies or wallpaper of similar tones. Alva joined her and some ten other young ladies in the Beekman drawing room, which looked out onto Tenth Street. Among those ten: Lydia Roosevelt, who upon seeing Alva assessed her figure and said, “Well, Mrs. Vanderbilt, who would have expected you here?”

Alva decided to attend a meeting of the Society for the Betterment of Working Children, which Armide had joined not long before. The group met once each month at the home of its president. Miss Annalisa Beekman was a young Knickerbocker lady whose pale eyes and pale hair and pale skin made her vulnerable to disappearance if she stood too near draperies or wallpaper of similar tones. Alva joined her and some ten other young ladies in the Beekman drawing room, which looked out onto Tenth Street. Among those ten: Lydia Roosevelt, who upon seeing Alva assessed her figure and said, “Well, Mrs. Vanderbilt, who would have expected you here?”

Vorwort

Vorwort